WORKING PAPER 6: A Littoral and Men: Sharing Fishing Resources in 18th Century Martinique

By Lucas Marin.

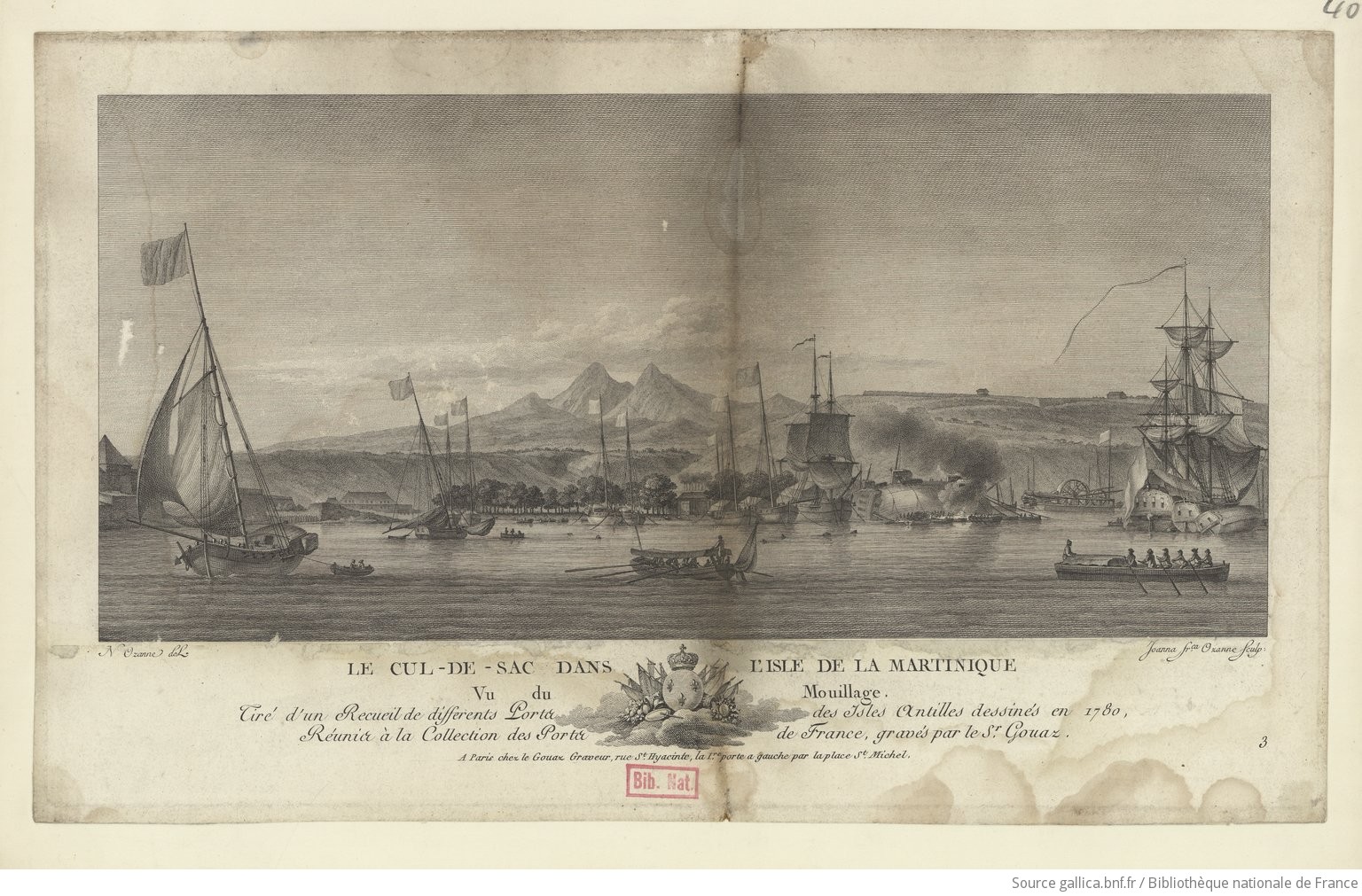

Le Cul-de-Sac dans l'isle de la Martinique, Pierre Ozanne, 1780, gallica.bnf.fr

Le Cul-de-Sac dans l'isle de la Martinique, Pierre Ozanne, 1780, gallica.bnf.fr

The initial results presented here are the fruit of research undertaken as part of my Master's degree at the Université des Antilles. My dissertation focuses on seamen in Martinique during the 18th century. The purpose of this work is to take a look at seamen through the legal texts promulgated in the French colony. In a way, it is about laying the foundations for what is to come. Although anthropologists have been studying seamen, and more specifically fishermen, in Martinique since the 1950s, historians have shown little interest in the subject.[i] My aim is to help fill this historiographical void.

This work takes a social history approach, studying the sociological profile of people who work at sea. It must take account of the specific features of slave-owning French Antillean colonial societies, and include the question of colour and the involvement of the enslaved in maritime activities. My future research will involve studying the operation of small maritime transport companies through notarial archives. The parish registers will also be interrogated in order to study the question of professional affiliation among Antillean seamen. These two types of documents will allow me to assess the role played by seamen in Martinican society and their relations with the rest of society.

Beyond this classic approach to social history, I also want to include an environmental and cultural reflection in this work. How can we ever ignore the question of man's relationship with his environment? We will see in the following paragraphs that studying fishing and fishermen allows us to see how colonial society viewed the resources it could extract from its environment. Finally, all these avenues of research will perhaps enable us to question the degree of "maritimity"[ii] of 18th century Martinican society. In this article, I will discuss two aspects of the wider dissertation on this topic, namely the preservation of fish stocks and the accessibility of fishery resources.

Preserving fish stocks: a challenge for the colonial authorities

On the 10th of January 1720, an ordinance was promulgated. It prohibited the hunting of game, in this case birds, for three months of the year. These months, April, May, and June, corresponded to the egg-laying season. The ban on hunting was presented in the preamble of the text as "the only practicable means of preventing the destruction [of birds]"[iii]. According to the ordinance, this was not the first measure to regulate hunting in order to preserve Martinique's bird population. However, despite these bans, local residents appear to have continued hunting during this period. Worse still, "the inhabitants not only disregard it, but even remove all the eggs they find, which is the certain cause of the scarcity of game". Nevertheless, the colonial administration did not despair. The decree of the 10th of January 1720 reiterated this ban, imposing a fine of 300 livres on offenders, with eight days' imprisonment in the event of a repeat offence. This seemed to be an important issue, as hunting "can be very useful, especially in a country where life and subsistence are very difficult". Indeed, even if protein-rich food was largely imported and consisted of salted fish and beef,[iv] local hunting and fishing provided a supplement, as shown by archaeological evidence.[v]

Hunting was not the only practice that the colonial administration tried to regulate. Fishing in the rivers and the sea was the topic of several ordinances during the 18th century. The earliest appears to date from the 2nd of April 1718, two years before the one concerning bird hunting. It concerns fishing by intoxication.[vi] This method, which was still in use in the mid-20th century, involved pouring a toxic substance into the water, in this case lime or "Conami-franc, known in our islands simply as bois-à-enivrer".[vii] The purpose of this was to bring fish to the surface by killing or stunning them. The ordinance banning it covers the use of this method in the island's rivers but is silent on the reasons for the ban. That said, the practice does not seem to have ceased, as on the 4th of May 1768, an "ordinance [...] concerning fishing" reiterated the ban and specified that fishing could be carried out in rivers as well as in marshes. Fishing was not the only activity covered by the 1768 order, which also prohibited the method of "diverting the course [of rivers] in certain places, and [...] Tritris fishing".[viii] The diversion of rivers, or fishing by diversion, dries up of an area of the watercourse and offers the opportunity to gather fish and crustaceans by hand.[ix] The "tritris", known today as titiris, are fry, the newborn fish of several species, whose fishing consists, according to the decree, of spreading a sheet or slick at the bottom of the water in the mouths of the rivers. The sheet is then used as a net. At this time, they used bed sheets because of the smallness of the fish, but nowadays fishermen tend to use mosquito nets instead. The ordinance of 1768 sheds light on the reasons that prompted the colonial administration to ban these practices. It informs us that the aim was to prevent "the destruction of fish" and thereby to maintain the adult fish population. By adding toxins to rivers or diverting their courses, anglers indiscriminately killed fish and other aquatic species. Meanwhile, titiris fishing preyed on newborn fish. All three practices target small fish and hinder the regeneration of aquatic species.

Between the ordinance of 1718 and that of 1768, we can observe a change in the penalties imposed on offenders with regard to the ban on fishing by intoxication. In the first decree, white offenders were liable to a fine of 50 pounds, "double that and three months' imprisonment in the event of a repeat offence". Enslaved people, for their part, incurred the penalty of the straitjacket for three consecutive market days, in addition to a month's imprisonment. In the event of a repeat offence, they were whipped, branded with a fleur-de-lys, and sentenced to three months in prison. In 1768, white offenders were sentenced to 5 years in the galleys, while freemen of colour and enslaved were sentenced to life in the galleys. Punishments therefore increased in severity over time. Under the Ancien Régime, the galleys took pride of place at the top of the hierarchy of punishments, just beneath the death penalty. This sentence involved civil death and the deprivation of liberty of the convicted person, as well as forced labour, and was considered a corporal punishment because of the suffering it inflicted.[x] The choice of the galleys as a punishment for fishing by intoxication perhaps reflects the colonial authorities' difficulty in combatting it. It may also reflect the particularly hard times in the colony and the consequent increase in fishing as a means of subsistence. The destructive cyclones of 1766 and 1767 caused considerable food shortages in the colony due to the destruction of reserves and food crops.[xi] The effects of these disasters were perhaps still being felt, and were forcing the colonial administration to combat a growing phenomenon that threatened the long-term survival of fish stocks.

From the 18th century onwards, these fishing and hunting practices were considered dangerous because they led to a decline in the population of certain species. However, it would be a mistake to attribute to the people of the past the same intentions that today lead us to protect animals and nature. In fact, it was not the colonial administration's intention to protect nature out of a concern for the environment. The measures taken were certainly protective, but their aim was to guarantee colonial society the continuity of the resources necessary for the survival of its members. As mentioned earlier, colonial island societies were largely dependent on imported foodstuffs, particularly meat and fish. However, the fact that such decisions were taken demonstrates the importance of local resources in the daily diet of the colony's inhabitants. What is more, it shows that, although colonial society considered nature to be a larder, the colonial administration was aware of the limits of the island's natural resources and the fragility of the ecosystem in the face of human abuse. However, the repetition of these bans suggests that this awareness was not shared by all members of colonial society. The resistance to the bans is perhaps further proof of the importance of fishing in their dietary habits.

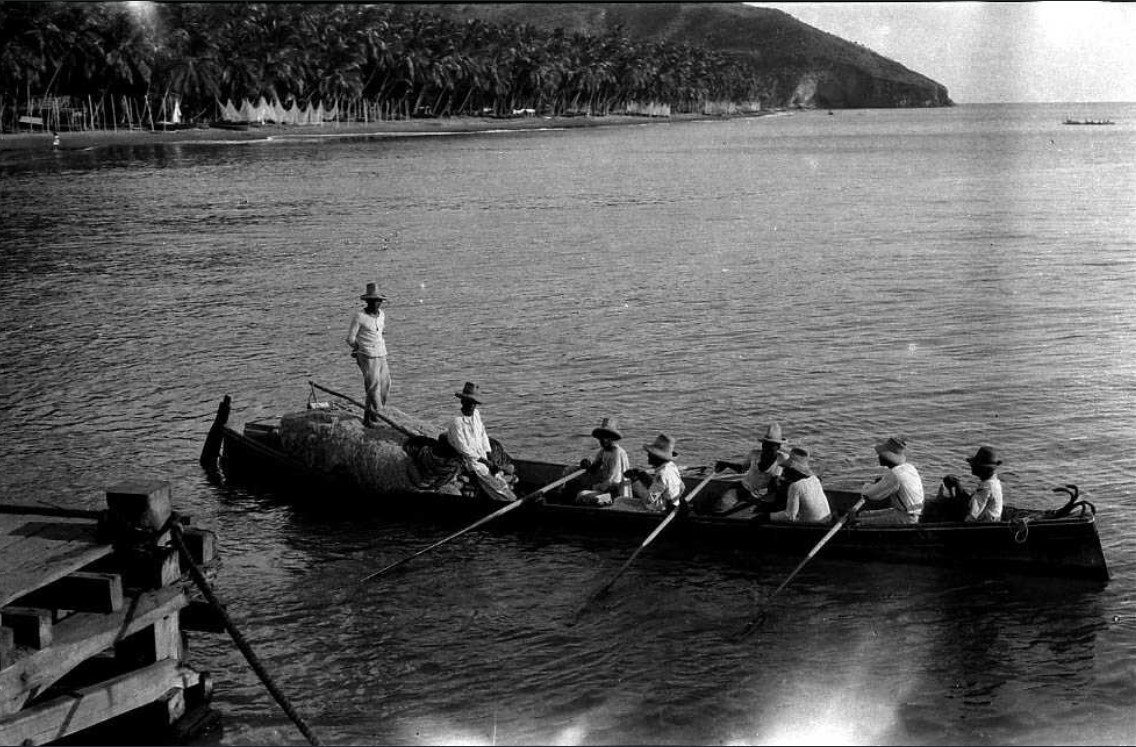

Carbet. Canot de pêcheurs, Jean-Baptiste Delawarde, 1937, Archives Départementales de la Martinique 31FI285. This photograph, although more recent than the period discussed, is representative of fishing as it was practiced from the 17th and 18th centuries until the 1950s. We can see the skipper of the canoe, standing on the fishing nets, and his crew.

Carbet. Canot de pêcheurs, Jean-Baptiste Delawarde, 1937, Archives Départementales de la Martinique 31FI285. This photograph, although more recent than the period discussed, is representative of fishing as it was practiced from the 17th and 18th centuries until the 1950s. We can see the skipper of the canoe, standing on the fishing nets, and his crew.

Accessibility of fishery resources: towards the creation of a regulated fish market in Martinique

The colonial administration, far from limiting itself to a policy of preserving fishery resources, also ensured that the resources were accessible. In January 1724, an ordinance was promulgated to regulate the prices of fresh foodstuffs necessary for the subsistence of Martinique's market towns. The ordinance stipulated that the price of pork and mutton must not exceed 12 sous per pound. There were different prices for fish, depending on their size. If it weighed less than a pound, it was sold at 7 sous 6 deniers per pound. If it weighed more than a pound, it was sold at 15 sous per pound. Fish was therefore more expensive than meat in 18th century Martinique.[xii] On the 27th of January 1766, another ordinance was promulgated, this time concerning fish and fishing alone. It stated that the colonial administration had been informed by residents of the market town of Saint-Pierre that the price of fish set by the ordinance of 1724 was not being applied. In addition to reiterating the price-fixing measures in the previous text, this ordinance intended to put an end to the practices considered to be at the root of these breaches.[xiii] In fact, we see the introduction of a number of measures aimed at guaranteeing the inhabitants of the market town of Saint-Pierre decent prices for their fish. First of all, the practice of enslaved people from Saint-Pierre going to nearby beaches to buy fish from fishermen and drag netters in order to resell them was prohibited. The practice was seen as contributing to rising prices and was therefore banned. However, since the ban had already been promulgated by a ruling in 1762, the ordinance did not stop there. Fishermen who sold their fish to these individuals were now liable for a fine. In addition, fishermen in the jurisdiction of Saint-Pierre were obliged to take their fish directly to the town centre, the hospital square, or the fort square. To enable the colonial authorities to exercise full control over the fishermen and ensure that they were punished if they failed to comply with these measures, they were required to declare themselves within eight days, giving their full names and addresses to the King's Prosecutor. These measures seemed to have some success, as on the 30th of June 1771, an ordinance repeated the same provisions, but this time for Fort-Royal. Fishermen from Anses-d'Arlets, Trois-Ilets, and Case-Navire were instructed to supply the town of Fort-Royal exclusively. As in the case of Saint-Pierre, places were designated for the sale of fish in the town. Fishermen from Anses-d'Arlets and Trois-Ilets were required to sell their fish "at the savanne at the end of Grande-Rue-Royale", while fishermen from Case-Navire were required to sell their fish "at the small square behind the Chapelle des Nègres".[xiv]

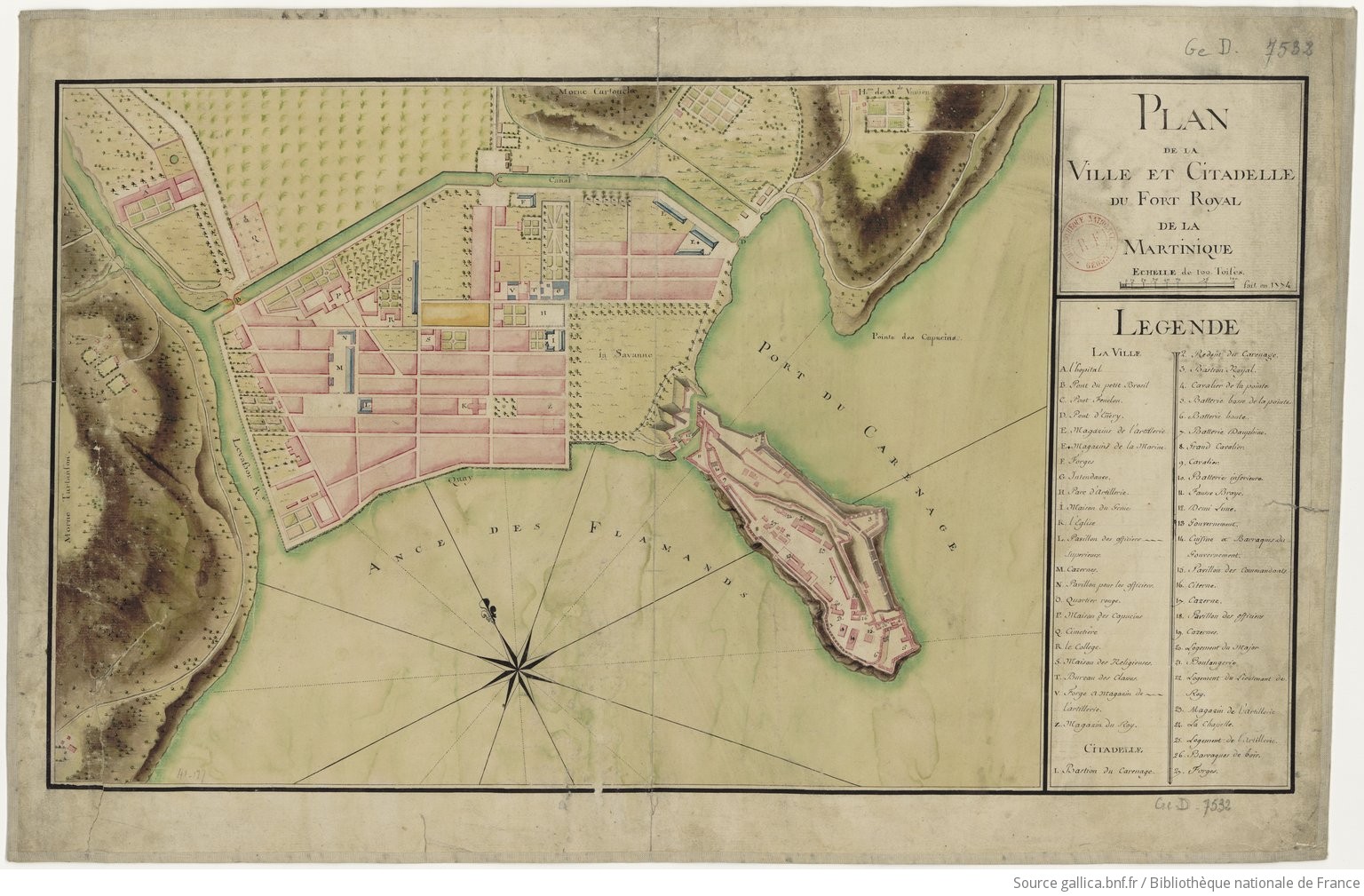

Plan de la ville et citadelle du Fort-Royal de la Martinique, 1774, gallica.bnf.fr. On this map, we can easily see the Place de la Savanne, where fishermen from Anses d'Arlets and Trois-Ilets sold their fish. As for the place where Case-Navire fishermen sold theirs, I have not yet been able to identify it on the various maps I have consulted.

Plan de la ville et citadelle du Fort-Royal de la Martinique, 1774, gallica.bnf.fr. On this map, we can easily see the Place de la Savanne, where fishermen from Anses d'Arlets and Trois-Ilets sold their fish. As for the place where Case-Navire fishermen sold theirs, I have not yet been able to identify it on the various maps I have consulted.

What do these measures tell us about the place of fish and fishermen in 18th century Martinique? Firstly, the measures of 1766 and 1771 aimed to ensure that urban populations had access to fisheries resources. The ordinance of 1773, which republished the provisions of 1766 and 1771, stated that fish was "above all a major source of sustenance in the most densely populated areas of Martinique, especially for the poor".[xv] Urban populations, who did not all have access to a plot of land on which to grow food or raise small livestock, were partly dependent on the fishermen who were requisitioned to serve them at a reasonable price. Fishing therefore seems to have had an importance that brought it into the realm of general interest. Although this activity was carried out principally by private individuals, some of whom did not depend on the colonial planters or even on the government, it is interesting to note that the colonial administration attempted, during the 18th century, to get involved in the organisation of fishing and the sale of fish. Fishing, which can be defined as travail pour soi,[xvi] "work that is self-organised by the individual [...] and whose fruits are self-consumed or exchanged on the market with the aim of acquiring other goods", saw its self-organised and independent character reduced by the measures. These measures could therefore be interpreted as undermining the freedom of trade and the profitability of fishing businesses. However, it was simply a matter of setting up a regulated fishing market to meet a real and vital need of the colony's urban populations. This concern to protect the poorest populations from food insecurity is reflected in the measures taken in these ordinances, in particular those regarding fish prices, but also in the measure prohibiting fishermen from selling their fish to innkeepers before they had served individuals.

On the 11th of March 1778, an ordinance further attacked the self-organisation of fishermen, this time by targeting the work of fishing itself and not the sale of fish. The preamble to this order stated that "by an ill-considered speculation, some individuals of the Case-Navire, having multiplied the number of their seines too much, in relation to that of their crew, have caused the public to experience the inconvenience of a shortage of fish that they are obliged to let escape, due to a lack of the necessary strength, while on the other hand, they uselessly occupy a space of sea that others would fill in a more fruitful manner".[xvii] The ordinance only authorised crews made up of "at least 6 negroes, including the skipper" to use drag nets, in order to avoid what it clearly considered to be poor occupation of space by fishermen who could not reel in all the fish they could catch. This desire to optimise space and harvesting capacity is in line with that observed in wartime in the plantations, when arable land is used for the production of foodstuffs necessary for survival. This concern about the effectiveness of fishing speaks volumes about its importance to the colony's inhabitants during the American War of Independence. A year later, in an ordinance dated the 28th of April 1779, the colonial administration clearly acknowledged the essential role played by fishing in wartime and in combatting the famine that accompanied it. The aim of this decree was to regulate the price of fish as fishermen were "abusing the moment of need" to raise prices. The decree nonetheless granted to a useful profession the possibility of a price increase.".[xviii] It ratified an increase in the price of fish to 10 sous per pound for those weighing less than a pound, and 20 sous for larger fish. This kind of favour, as well as the way it was justified in the ordinance, confirms what the previous texts had already, i.e. the importance of fishing. It allows us to see that this practice, in times of war, could play a vital role in the survival strategy of the colony.

Conclusions

The data collected and presented in this article are part of a preliminary study of a subject at the crossroads of social and environmental history. The ordinances banning certain fishing methods have enabled us to observe a real policy of preserving fishery resources on the part of the colonial administration, despite a certain reluctance on the part of the population. Secondly, this preservation seems to have been accompanied by the establishment of a regulated fishing market, as well as recognition of the importance of fishing resources and therefore of fishermen in the life of the colony, particularly in times of war. Finally, the theme proposed in this chapter should be developed in the future through the contribution of other sources, which will perhaps enable study of the sociological profile of the fishermen mobilised and of those who violated the bans we have seen.

[i]J. BENOIST, "Individualisme et traditions techniques chez les pêcheurs martiniquais" in Cahiers d'outre-mer, N° 47 - 12e année, Juillet-septembre 1959, pp. 265-285. R. PRICE, "Magie et pêche à la Martinique" in L'Homme, 1964, tome 4 n°2, pp. 84-113. I. DUBOST, De soi aux autres… Un parcours périlleux : la construction d'un territoire par les pêcheurs martiniquais, thèse de doctorat en anthropologie sous la direction de Aliette Geistdoerfer, Université Toulouse 2, 1996.

[ii] F. PERON and J. RIEUCAU, La maritimité aujourd’hui, Paris, 1996.

[iii] Code de la Martinique, n° 56, Ordonnance de MM. les Général et Intendant, qui défend la chasse durant trois mois de l'année, 10 janvier 1720.

[iv] G. DEBIEN, "La nourriture des esclaves sur les plantations des Antilles françaises au XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles«, Caribbean Studies, vol. 4, n° 2, 1964, p. 6.

[v] S. GROUARD, Y. HENRY and N. TOMADINI, "L'Alimentation dans une plantation guadeloupéenne du XVIIIe siècle. Le cas de l'habitation Macaille (Anse-Bertrand)", in B. BERARD and K. KELLY (dir.) Bitasion : Archéologie des habitations- plantations des Petites Antilles / Lesser Antillean Plantation Archeology, Leiden, 2014, p. 69-85. K. KELLY, "La vie quotidienne des habitations sucrières aux Antilles : l'archéologie à la découverte d'une histoire cachée", In Situ, 2013.

[vi] Code de la Martinique, n° 49, Ordonnance de MM. les Général et Intendant, sur l'enivrement des rivières, 2 avril 1718.

[vii] ANONYME, Dissertation sur les pesches des Antilles, manuscrit anonyme (1776), Sainte-Marie, 1975, p. 23.

[viii] Code de la Martinique, n° 398, Ordonnance de MM les Général et Intendant, concernant la pêche, 4 mai 1768.

[ix] M. COTTET, A. RIVIERE-HONEGGER and B. MORANDI, "La pêche en Martinique : quels sont les jeux d'une patrimonialisation environnementale ?", in Etudes Caribéennes, n° 41, december 2018, p. 19.

[x] M. VIGIE, "Justice et criminalité au XVIIIe siècle : le cas de la peine des galères", in Histoire, économie et société, n° 3, vol. 4, 1985, p. 345-346.

[xi] O. COSPAR, M. JEAN-VALERY and P. SAFFACHE, Les cyclones en Martinique ; quatre siècles cataclysmiques, Paris, p. 29-31.

[xii] Code de la Martinique, n° 87, Extrait d'une ordonnance de MM. le Général et Intendant, sur la police des bouchers, boulangers, poissonniers et marchands de légumes, d'herbage et de lait, pour l'approvisionnement des bourgs, janvier 1724.

[xiii] Code de la Martinique, n° 347, Ordonnance de MM. les Général et Intendant, pour la vente du Poisson, 27 janvier 1766.

[xiv] Code de la Martinique, n° 445, sur la vente du Poisson dans la ville du Fort-Royal, 30 juin 1771.

[xv] Code de la Martinique, n° 481, Ordonnance de MM. le Général et Intendant, sur la vente du Poisson à Saint-Pierre et au Fort-Royal, 5 décembre 1773.

[xvi] C. OUDIN-BASTIDE, Travail, capitalisme et société esclavagiste. Guadeloupe, Martinique (XVIIe-XIXe siècle), Paris, 2005, p. 187.

[xvii] Code de la Martinique, n° 542, Ordonnance de MM. les Général et Intendant, concernant la Pêche et la vente du Poisson, 11 mars 1778.

[xviii] Code de la Martinique, n° 559, Ordonnance de MM. les Général et Intendant, concernant le Prix et la Vente du Poisson, 28 avril 1779.