Antillean Canoes

How did islanders in the Lesser Antilles connect? What infrastructure supported ties between small islands? To answer these questions, we have begun an archival quest for canoes, bum-bum boats and other small seagoing vessels in the region. Already now, after only a few weeks of research, it is evident that we have to imagine the region as whirring with small boats continually navigating around and between the islands, islets, and bays, crisscrossing imperial boundaries, shunning the gaze of local authorities, creating new ties in local networks, and offering opportunities for inhabitants of the various colonies, both free and unfree.

The very nature and presence of the canoes was a manifestation of the discrepancy between imperial ambitions for complete control and the unruliness of colonial populations and geographies; a discrepancy that forced legislators to take preventive action and carry through laws that aimed at regulating the movement of canoes and other small boats.

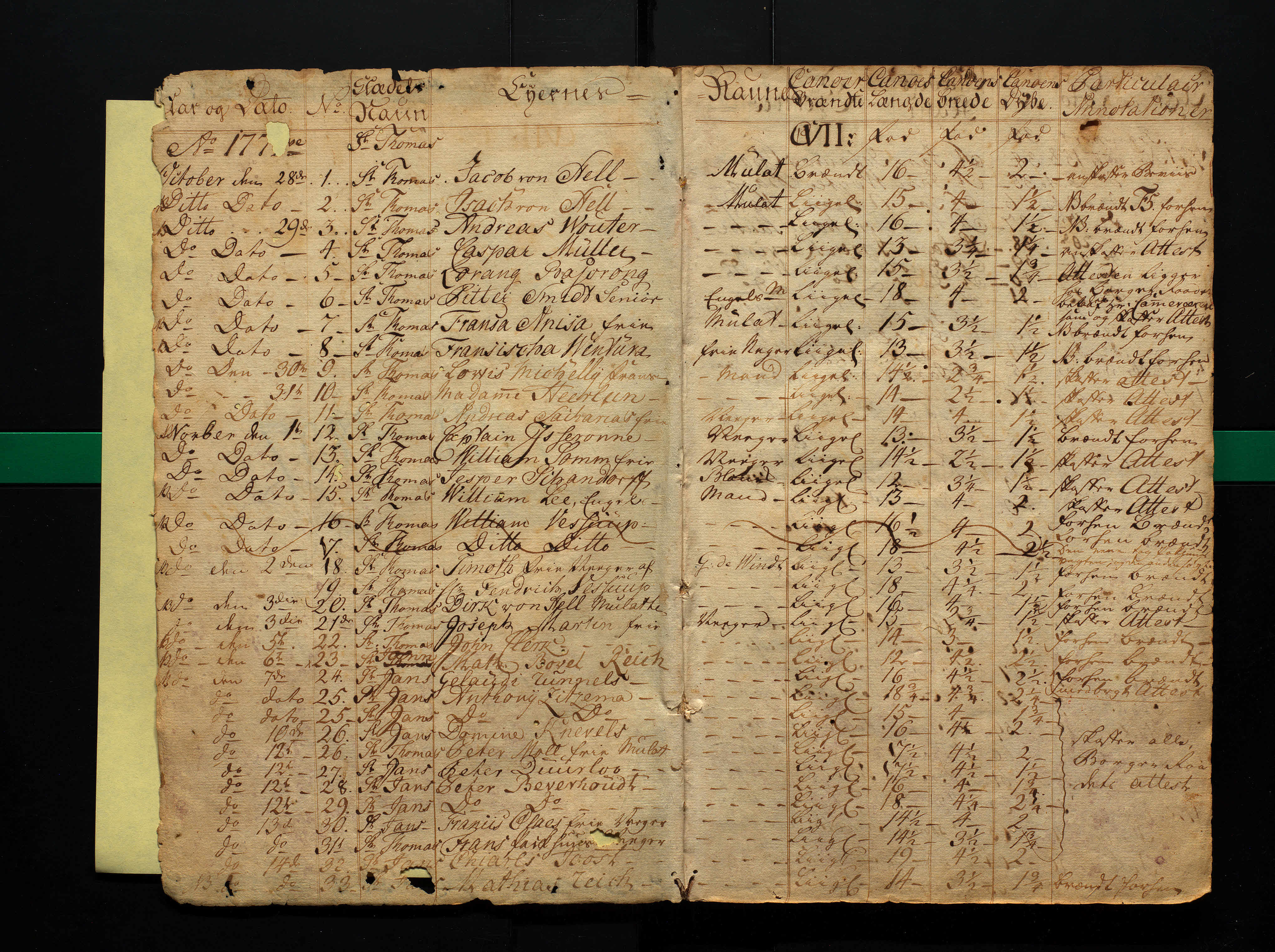

One of our interesting finds is registers of canoes and small boats in the former Danish West Indies (today the US Virgin Islands). On St. Thomas and St. John alone, the authorities recorded just below 1.500 small vessels in the period from 1771-1815.

In these canoe registers, colonial officials recorded the name of the canoe owner, its year of registration, its mark (typically the monogram of the Danish king), its size, length, width, and depth, and if the canoe had a mast. One notable observation is that approximately 22 per cent of the canoes on St. Thomas and St. John were owned by free people of colour, suggesting that they had a relatively large share in maritime activities such as local trade, fishing, and ferrying carried out by these smaller seagoing vessels.

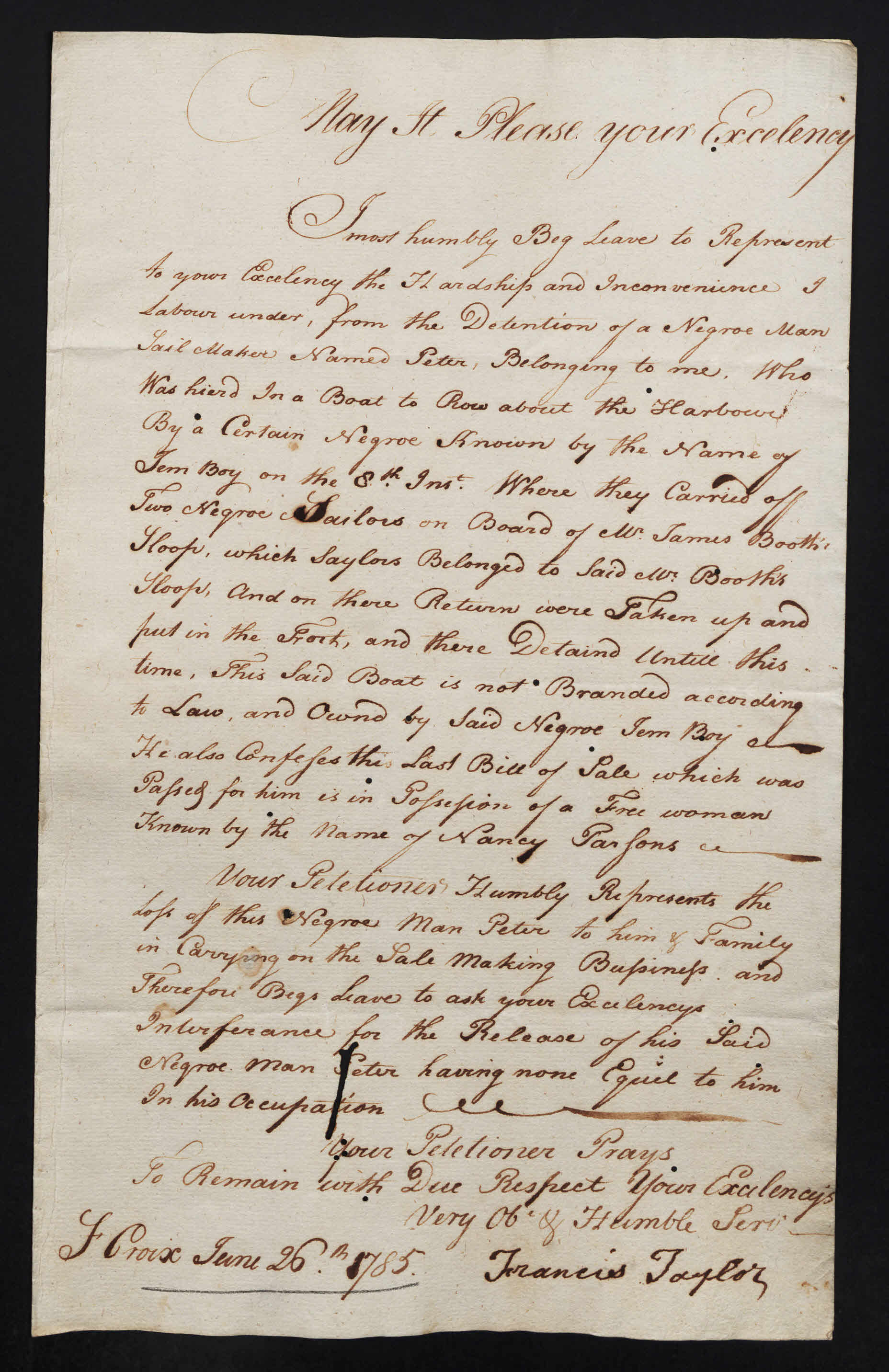

Canoes and small boats were difficult to control, however. In 1785, Francis Taylor wrote to the Danish authorities, recounting the story of one Jem Boy, who used his canoe – which had not been properly branded – to hire an enslaved man, Peter, to “Row about the Harbour” and carry off black sailors. Peter, a sailmaker, belonging to Taylor, had ended up in detention for his role in the capture, kidnapping or rescuing of the black sailors. Now Taylor petitioned for his release.

We are very excited by the findings and we look forward to diving further into the history of canoes and small boats in the Lesser Antilles in the coming months.