Mary Sadler: Curse Words and Gentility in St. Eustatius, 1801

By Felicia Fricke.

When we think of early eighteenth century language, we often think of a formal and convoluted writing style. However, we also know that people in this period had strong emotions expressed either verbally or in writing, sometimes using language that remains shocking today. Ale Pålsson’s recent article in the Scandinavian Journal of History includes examples of enslaved women and free women of colour using insults such as “salt pond whore” on the Swedish island of St. Barths in 1835.[i] In this short blog post, I examine a similar instance concerning a white woman on the Dutch island of St. Eustatius in 1801. Such behaviour transgressed what was expected of respectable free women.

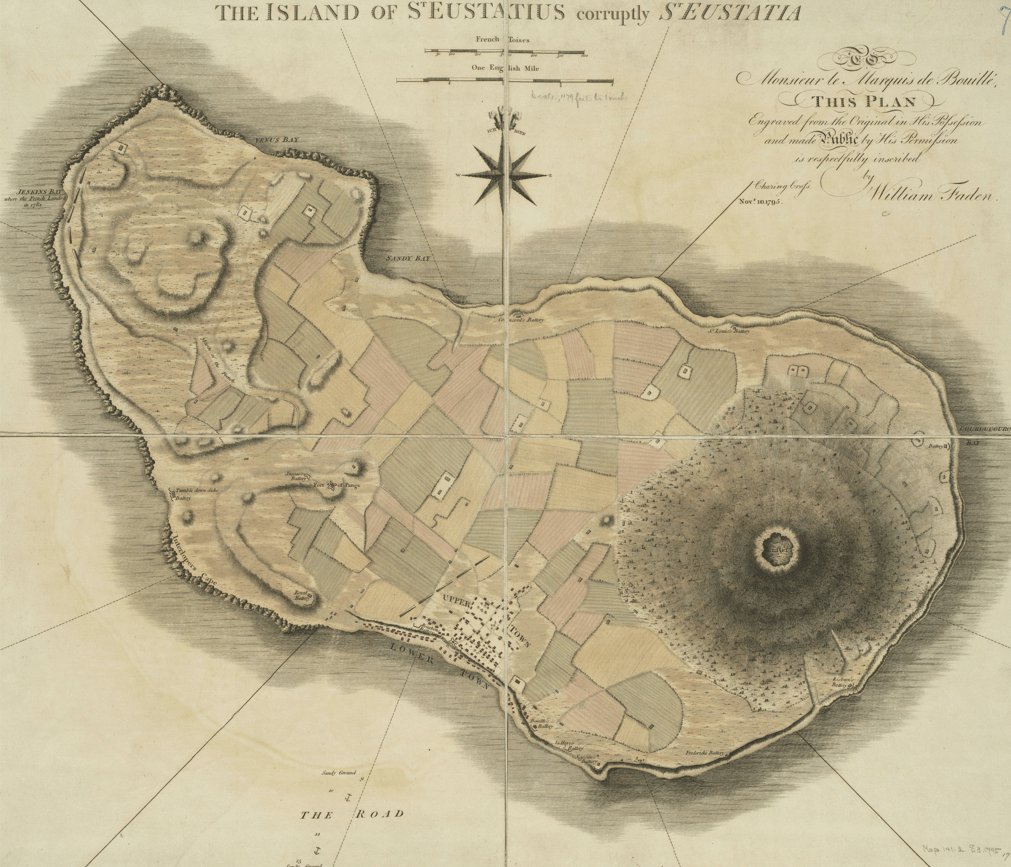

Figure 1. The Island of St. Eustatius corruptly St. Eustatia, Novr. 10, 1795, William Faden.

Figure 1. The Island of St. Eustatius corruptly St. Eustatia, Novr. 10, 1795, William Faden.

Mary Sadler was an unmarried woman with a sharp temper and difficult family relationships, particularly concerning her brother, a seaman named Christopher (also known as Kitt) and his common-law wife Joanna Catharina Fabio.[ii] In August 1801, a disagreement between the siblings made Christopher so angry that he called Mary a “bitch”, and having flung this scandalous epithet he might have thought that this would be the end of the matter. On the other hand, he might have known his sister too well to believe that he could have the last word. Perhaps he was left with an uneasy feeling, wondering what Mary might do in retaliation. What she would do, would reveal some of the era’s most insulting language – language so offensive, that Christopher would feel compelled to involve the colonial authorities.

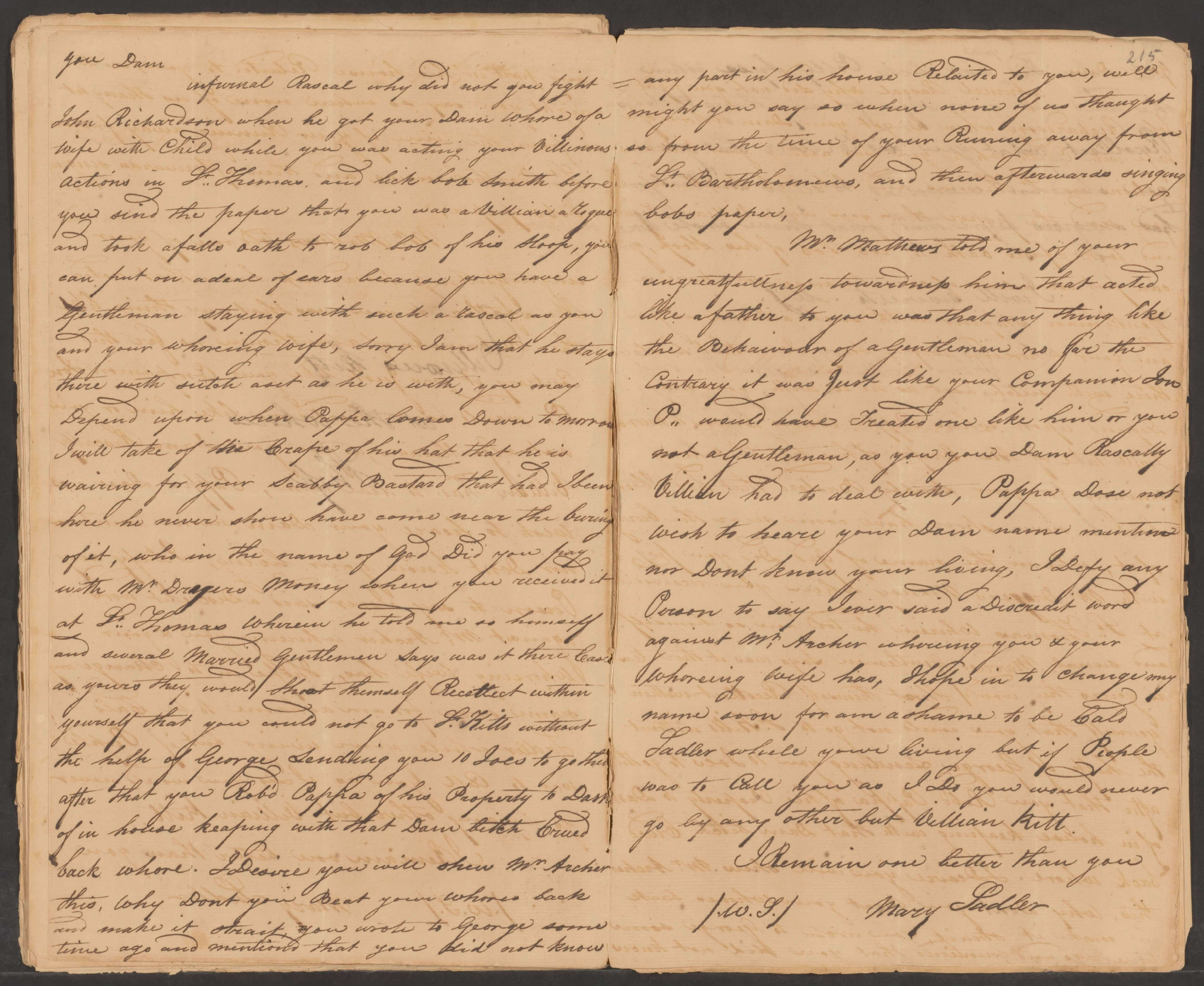

In the small free section of colonial Caribbean society, rumours travelled fast. As Jessica Roitman and others have shown, rumour and gossip could be used by elites to police the boundaries of social acceptability.[iii] Potential infidelities were one of the most damaging and volatile types of rumour because they threatened the nuclear family, which was tied very closely to lines of succession and the inheritance of colonial assets.[iv] In this case, in St. Eustatius, such a rumour had circulated about Joanna. While Christopher was away in St. Thomas, it was alleged that Joanna had slept with and become pregnant by a man named John Richardson. Referring to Joanna as “your Dam Whore of a Wife” and “that Dam bitch Crued [crooked] back whore”, Mary asked Christopher in a letter why he had not fought John over it, calling into question her brother’s dignity and masculinity. What made this even more inappropriate was the fact that the child in question (whom Mary called a “Scabby Bastard”) had previously passed away.

Figure 2. Copy of Mary’s letter to Christopher (NL-HaNA, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba tot 1828, 1.05.13.01, inv.nr. 149 Protocollen van secretariële en notariële akten, p. 220).

Figure 2. Copy of Mary’s letter to Christopher (NL-HaNA, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba tot 1828, 1.05.13.01, inv.nr. 149 Protocollen van secretariële en notariële akten, p. 220).

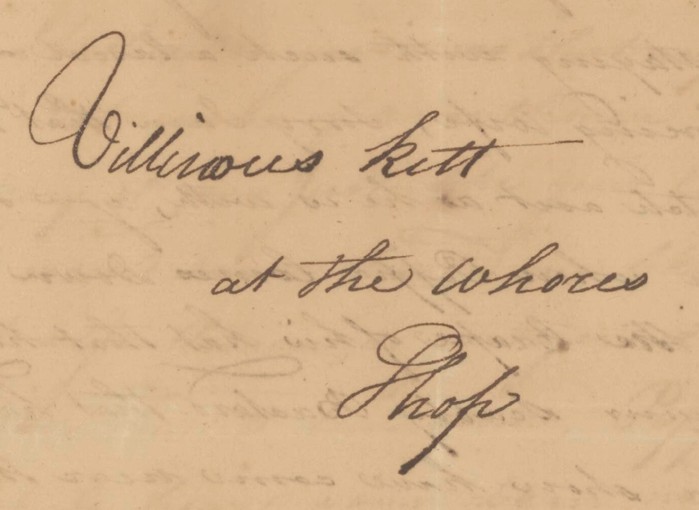

However, the rumour of infidelity and Christopher’s reluctance to act upon it seemed to be responsible for only a small part of Mary’s wrath. Over the years, she had been repeatedly exasperated by her brother’s “villainous” behaviour, and now took the opportunity to lay it all out. Mary blasted Christopher with the accusations that he was a false oath taker, a thief of money and property, a runaway from his responsibilities, a social climber, a cuckold, an ingrate, a disappointment to his father, an insufficiently dominant husband, and certainly not a gentleman. She advised him that he should beat his wife “strait”, that he should more diligently punish an enslaved woman named Polly Syss (ironically, in retaliation for insulting Joanna), and that the gentlemanly thing to do might be to shoot himself. Mary closed her letter by saying “Ihope [sic] in to change my name soon for am ashame to be Cald Sadler while your living […] I Remain one better than you”. Sealing and addressing the envelope (see Figure 3), and possibly still shaking with anger, Mary handed it to an enslaved girl named Jinney for delivery to her brother’s house.

Figure 3. Mary’s letter to Christopher was addressed to “Villinous Kitt at the whores Shop” (NL-HaNA, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba tot 1828, 1.05.13.01, inv.nr. 149 Protocollen van secretariële en notariële akten, p. 219).

Figure 3. Mary’s letter to Christopher was addressed to “Villinous Kitt at the whores Shop” (NL-HaNA, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba tot 1828, 1.05.13.01, inv.nr. 149 Protocollen van secretariële en notariële akten, p. 219).

On receipt of these blistering accusations, Christopher must have been alarmed. The rumour about Joanna and John Richardson may already have been common knowledge; however, repeating it was unlikely to do anyone much good. In addition, some of the other accusations, such as theft and false oath-taking, were for actions that were illegal, and could have landed him in trouble if the stories acquired legs. Christopher leapt into action. He had received the letter on August 18 – on August 20, he was already standing before Hendrick William Pandt, the island secretary, asking for his help. Not daring to repeat Mary’s words, Christopher referred to them only as “Scurrilous and Injurious language, tending to defame my Charactor and Wife’s”.[v] He threatened to issue “an Action for Defamation” if Mary did not retract her statements. The island secretary, Hendrick, was to relay this information to Mary, accompanied by the siblings’ father, John Sadler. However, perhaps a long-suffering peacekeeper for warring children, Mr. Sadler would in this case defend neither of his offspring. The island secretary was therefore forced to go alone.

When Hendrick arrived at her abode, Mary had already had two days to think about her actions and had repented to a certain extent. In a letter to Joanna dated August 19, she wrote: “Madam, What I said concerning you in the letter to your husband I am sorry for, & hopes you will think nothing of it as it was done when I was in a passion to think what he said about me, let me beg you to forget it as you may depend I will”. As for apologising to her brother, Mary stood her ground. She maintained that “if he was sorry for what he had said to her, she then would likewise be sorry for what she had said of him”. After this, we hear no more from either of the Sadlers, and can perhaps assume that they eventually apologised to one another. Four years later, Christopher and Joanna got married and Christopher acknowledged both of their surviving children.[vi] They were still a young couple, and the accusations of adultery had not destroyed their union. Mary Sadler, however, appears nowhere in the marriage registers. Perhaps she succeeded in changing her name and removing from herself the detested association with her “Rascally” brother.

Overall, this episode in the lives of St. Eustatius’ colonial elites is a stunning example of early nineteenth century profanity – this time, from a white woman. In doing so, Mary threatened her social network (not only her relationship with her brother and sister-in-law, but also her relationship with her father), exposed herself to potential legal action, and transgressed what was expected from a person of her gender, race, and social status. Although her actions were rash, they reveal to us the seldom-seen internal world of a colonial era Caribbean woman, providing insight into what free women might have considered important and appropriate in their male counterparts, aspiring to membership of the gentry in a colonial context.[vii] In Mary’s view, a gentleman paid his debts, kept his oaths, honoured his family, expressed gratitude, and did not steal. However, he was also violent towards his sexual competitors, his slaves, his wife, and in extremis even towards himself.

[i] Ale Pålsson, ‘“Insolent, Quarrelsome, Noisey and Troublesome”: Women’s Street Fights and Noise in St Barthélemy in 1835’, Scandinavian Journal of History, 2024.

[ii] Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba: Oude Archieven tot 1828, nummer toegang 1.05.13.01, inventarisnummer 149 Protocollen van secretariële en notariële akten, p. 216-221.

[iii] Felicia Fricke, ‘“It Is Only Bad Priests and Outlaws Who Thrive NowAdays”: The Catholic Church, the Colonial Authorities, and Elite Rumor Networks in the 1820s Lesser Antilles’, New West Indian Guide 98, no. 1–2 (2023): 59–91, https://doi.org/10.1163/22134360-bja10027; Jessica Roitman, ‘The Repercussions of Rumor: An Adultery Case from 18th Century Curaçao’, in A Sephardic Pepper-Pot in the Caribbean: History, Language, Literature, and Art, ed. Michael Studemund-Halevy, Fuente Clara 36 (Barcelona: Tirocinio, 2016), 124–35.

[iv] Roitman, ‘The Repercussions of Rumor: An Adultery Case from 18th Century Curaçao’; Christine Walker, Jamaica Ladies: Female Slaveholders and the Creation of Britain’s Atlantic Empire (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 33–34, 57, 130.

[v] NL-HaNA, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba tot 1828, 1.05.13.01, inv.nr. 149 Protocollen van secretariële en notariële akten, p. 216.

[vi] NL-HaNA, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba tot 1828, 1.05.13.01, inv.nr. 243 Registers van ondertrouw-aangiften en huwelijken. Met bijlagen, 1803 mei 28 – 1809 december 9, p. 9.

[vii] Expectations for and traits of gentlemen in colonial societies were different from in Europe, see Michal J. Rozbicki, The Complete Colonial Gentleman: Cultural Legitimacy in Plantation America (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998), 28–38.