WORKING PAPER 5: Enslaved Mobility in Grenada: A Snapshot

By Heather Freund, 26 September 2022.

In this working paper, Heather Freund uses newspaper runaway lists to develop a map of runaway origins and destinations on Grenada in 1819 and 1825. She identifies common pathways and the possible reasons why enslaved people chose these locations for escape.

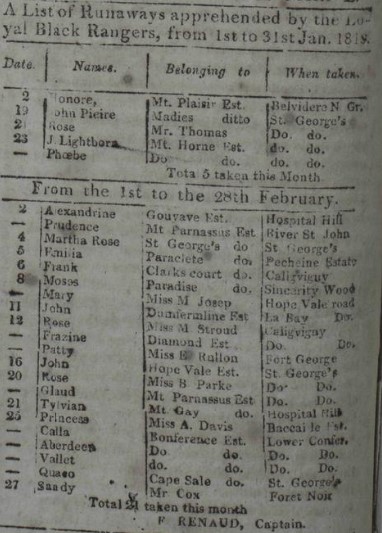

In the years 1819 and 1826 the St. George’s Chronicle, and Grenada Gazette published a total of ten lists of “Runaways apprehended by Loyal Black Rangers” covering some or most of the years 1819 and 1825.[1] They include 257 individuals, most of them

Figure 1: “A List of Runaways apprehended by the Loyal Black Rangers, from 1st to 31st Jan 1819 and From the 1st to the 28th February”

named. We only have August-December for 1825 but all but December for 1819. The number of runaways for 1825 is roughly half what it was for a similar period in 1819.[2] What changed in the intervening six years?

The lists of apprehended runaways were printed beginning on March 15, 1815 when The St. George’s Chronicle and Grenada Gazette reported that “The Governor considers it highly necessary and proper to direct, that the weekly Returns of the services of the Loyal Grenada Rangers should be published weekly, in the Grenada Gazette.”[3] These lists do not always appear, and the information they contain varies. This blog post uses a selection of the lists to construct a map of where the enslaved ran from and were captured. The maps consulted were completed by French surveyor Jean-Baptiste Pinel in 1763 and British surveyor Daniel Patterson in 1780, and a detailed map done in 1801 by Gavin Smith. Paterson and Smith also provide a list of proprietors, the names of their estates, and the crops grown.[4]

Newspapers commonly published runaway slave advertisements and lists of runaways who were being held in the jail. With these ads, we usually only know the name of the runaway and the name of their enslaver or what estate they lived on. We rarely find out if their bold escape for freedom was successful or where they went. Sometimes an ad will include language such as “has been seen about St. George’s” (the capital of Grenada), but typically we can only guess about the literal paths to freedom these men and women took. The lists that form the basis of this blog post are unique among those published because they include the names of the enslaved, who claimed them as their property, and where they were captured. Compiling the lists of runaways allows us to focus on where these men, women, and children ran from and where they were captured to look for patterns and imagine the pathways they took. The resulting map below attempts to visualize this information. Some estates come up repeatedly in the lists. Is this simply because they were particularly large estate? If more people fled an estate around the same time, perhaps there was a new driver or estate manager who was cruel or negligent; or maybe a natural disaster or unusual scarcity created even harsher living conditions for the enslaved workers.

The common narrative for marronage is that most runaways tried to get to cities to blend in or to try to get on board a ship to escape the island.[5] The map shows that many seem to have done that, but clearly not all. The dots and lines begin to illustrate the fugitive landscape in Grenada. We know that some areas closer to the interior were forests, and remain so to this day, such as Grand Etang, an area that included a large pond. The pond would have been important for runaways to have access to fresh water. At least some of this area was identified as Crown Land, meaning an individual did not own it. Most of it was in the interior, which was unsuitable for large scale plantation agriculture because of the difficult terrain. Depending on the nature of the enslaved’s labour, the roads connecting different parts of the island may not have been part of what Rebecca Ginsburg terms the “black landscape,” defined as “ways that enslaved people knew the land [and] the modes by which they made sense of and imagined their surroundings.” It was “the system of paths, places, and rhythms that a community of enslaved people created as an alternative, often as a refuge, to the landscape systems of planters and other whites.” [6] She notes that enslaved people viewed the landscape differently than their enslavers since they experienced it differently. They might be looking for places in which they could hide or steal food to supplement their meager rations. The planter, overlooking the fields, was interested in control of his estate from his physically imposing position, likely on top of a hill. Forests, which could be places of refuge for the enslaved, were often cast as places of danger for whites, who preferred not to enter them in search of runaways, which is why they employed Black Rangers. Maroons were forced to create settlements out of inhospitable parts of the island, places where they were less exposed to capture.

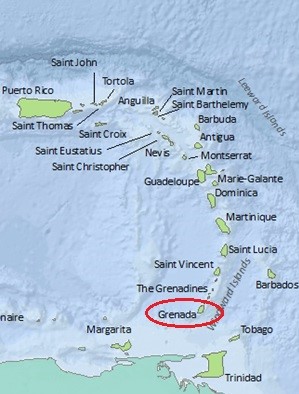

Figure 2: Map of the Lesser Antilles (Map by Aaron King, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign)

Grenada is an island in the south-eastern Caribbean, part of the Windward Islands. It is small and volcanic, heavily forested and mountainous. It was controlled by France from the mid-seventeenth century until the British captured the island in 1762 during the Seven Years’ War; it was ceded to Britain along with other French islands and imperial holdings in the Treaty of Paris of 1763. Grenada was a complex and divided society from the time it became British because of confessional and cultural differences between old and new inhabitants. It was recaptured by the French from 1779-1783 during the American Revolution, then returned to the British. The spread of the French Revolution (1789-1799) to French Caribbean possessions caused further upheaval in the British islands and the region as a whole. Fedon’s Rebellion (1795-6) was led by Julien Fedon, a free man of color and planter, and nearly led to the toppling of British rule in Grenada; he captured and executed the governor and other prominent white men. He was joined by most of the French inhabitants, free people of color, and about half the enslaved population of the island. The plantations were almost all destroyed.[7]

By the early nineteenth century, sugar cultivation was in decline in the British islands for economic reasons and the movement toward abolition of the slave trade and slavery. As George Brizan notes, many estates on Grenada had been abandoned or neglected: “Of Grenada’s 342 estates in 1824, 86 were in bush and pasture.” There were also maroon settlements in the wooded interior of St. John’s parish and the highlands of St. Andrew’s and St. David’s.[8] Abandoned plantations would have also aided runaways, affording places to hide and potentially food if crops still grew in provision grounds.

The British used Rangers as guerilla fighters, generally to search for runaway slaves and to destroy maroon camps. The Loyal Black Rangers were enslaved men who served the colony in various capacities, primarily in the hunting of runaway slaves. Their officers were white. They were, as one writer put it, “employed in relation to Slaves, chiefly to arrest runaways, but generally to maintain the master’s lawful authority as an armed Police.” (emphasis in original)[9] If they were maimed or killed in service, their owners were paid out of the colonial treasury. They originated in Fedon’s Rebellion, when black troops were raised to fight the insurgents, to great effect. When those corps were no longer needed, the legislature found it “expedient to form a Black Corps upon a new Establishment.” Under the revised act: “Three Companies of able bodied Slaves of eighty Rank and File each (to be distinguished by the name of The Loyal Grenada Black Rangers) shall be raised, drawn out, embodied, armed and arrayed.”[10] Sometimes long service could lead to freedom, as an entry in the accounts of Grenada stated that “a Sum not exceeding Eighty-two Pounds Ten Shillings be placed at the disposal of the Deputy Treasurer of this Colony, for the purposes of purchasing the freedom of Serjeant Mitchel, who has long and faithfully served in the Loyal Black Rangers.”[11] Rangers were paid from colonial funds to hunt runaway slaves and otherwise support British troops. This would have been in addition to the colonial militia, which Brizan notes handled slave vagrancy, rebellions, and other disturbances the estates could not handle themselves.[12] Black troops were indispensable to colonial security.

The Creation of the Map

One would not see Grenada’s tumultuous history from looking at the names of estates and towns on Smith’s 1801 map. The eighteenth century disruptions, along with the usual precarity of life in the Caribbean as a result of hurricanes, fires, disease, and indebtedness, meant that plantations changed owners often or were abandoned entirely. Even in these cases, however, the names did not always change. Plantations with French names were sometimes owned or managed by British planters or attorneys, symbolizing the history of colonialism in the small island.[13] We see both English and French names for estates and towns, as the island’s population remained British and French. For example, Grenville was formerly known as La Bay and Gouyave became Charlotte Town. Even if the British renamed a town or parish, often the French name persisted among the inhabitants. One sees both English and French names even in the correspondence of British officials, acknowledging the lived reality of the inhabitants under the colonial regimes.

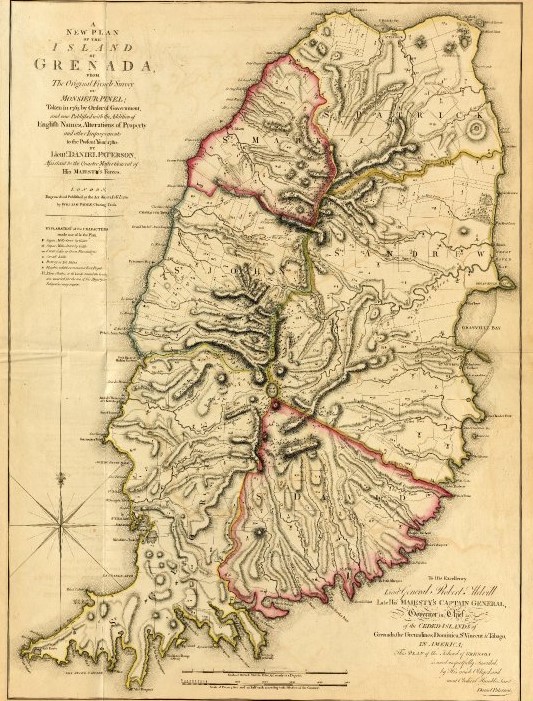

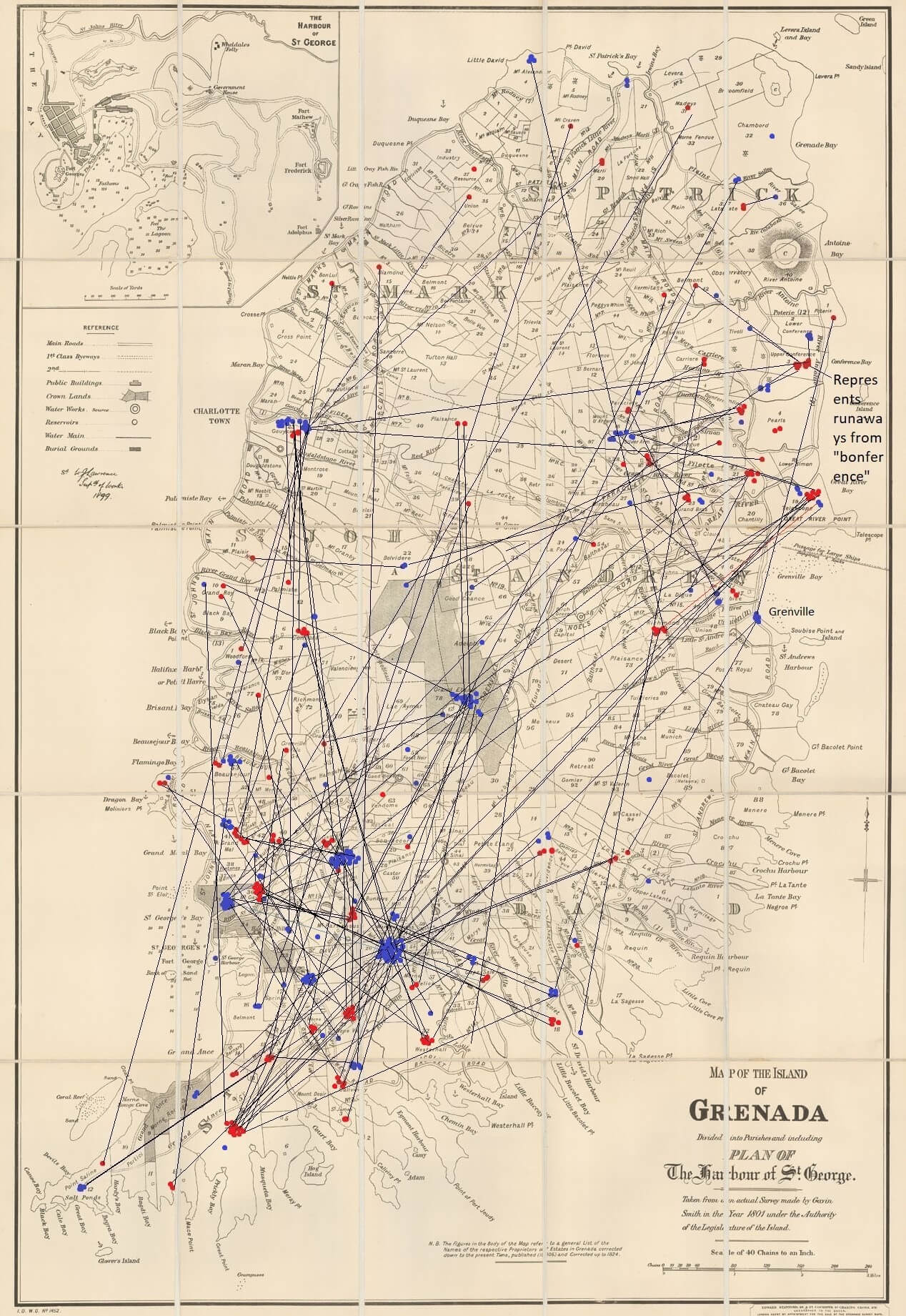

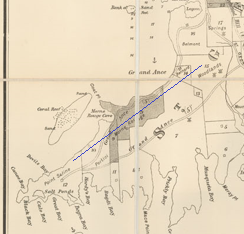

As previously noted, this blog post uses maps and lists of proprietors by Pinel completed in 1763, Patterson in 1780, and Smith in 1801. Plotting was done using Smith’s map because it was completed the latest and includes names of estates. Pinel’s map is also included below because it illustrated some topographical features that are helpful for understanding why runaways would seek refuge in certain parts of the island. One can see the mountainous ridges in the interior that would have been difficult to search. The Legacies of British Slave Ownership database (hereafter LBS), which contains information about plantations in the British islands of the Caribbean was also helpful for finding estates from the runaway lists by providing the parish in which they were located. LBS is compiling information on British slave ownership throughout the Caribbean and has maps-in-progress with estate information for Jamaica, Barbados, and Grenada.[14] On Smith’s map, the red dots note record embarkation points. Blue dots are where the enslaved were caught by the Rangers. Lines connect the two. If site is a road or a river, I have plotted the location next to the name label of said road or river.

Figure 3: Jean-Baptiste Pinel, Map of Grenada, 1763, Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library

Figure 4: Gavin Smith, Map of the Island of Grenada, 1801, Courtesy of the Map Library, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Plotting can be imprecise for various reasons. Sometimes the runaway named an individual as their owner; perhaps they were urban slaves hired out for wages. In these cases, generally only the place of capture is recorded since only rarely was it possible to link the name with an estate. Even with estate names, it can be difficult to identify where an enslaved person tried to escape from or where they were captured because the names of estates were duplicated. For example, there are five estates called Bacolet, and three Belmonts on Smith’s map; some entries list Conference as the estate, but there is Upper Conference and Lower Conference.

Sometimes it seemed reasonable to guess that the plantation of departure for a runaway was the one closest to the one on which they were caught, but this is obviously prone to errors. For example, a man named John from the June 1819 list is identified as being from Plaisants (likely Plaisance) and was captured “Above Silver Arm” Estate, in St. Patrick Parish. According to Smith’s map, there are three Plaisance Estates in the general area: in St. George, St. Patrick, and St. Andrew Parish. Each of the estates had a road running through or near it. Only a list of people on each plantation could potentially answer where John’s Grenadian home was, but he had a common name so it is difficult to say.

Paths of Marronage in Grenada

Certain parts of the island appear to have more runaway activity, The most activity is in the southwestern part of the island, in the vicinity of the capital, which is unsurprising. There seems to be a fair amount of movement between the southwestern part of the island and the north, around Gouyave. The area north of Grenville, another major town, and south of the River Antoine in St. Andrew parish also demonstrates quite a lot of marronage. Lines between sites on the map are obviously not meant to illustrate the path a fugitive would take but rather serve to visualize distance traveled. Those who fled from a plantation in St. Andrew parish on the eastern coast to St. George parish on the other side of the island either had to travel by boat or through the mountainous, heavily forested island interior. There were roads, but these would have been patrolled and traveled by whites. Perhaps the roads that went through the interior, like Grenville Road, helped runaways find maroon camps.

When looking at locations where runaways were captured, some come up frequently. Perdmontemps (often misspelled as Perdmontems on the lists) appears 36 times as a place where fugitives were captured – the most of any – but nowhere on Smith’s map of estates. Only by reading elsewhere do we find out it was also called Good Hope, perhaps an example of plantation renamed after transfer from French to English owners.[15] One gets the sense that there was likely a maroon camp there, which the Rangers would have been sent to destroy. Good Hope Estate appears to have been partly wooded, so perhaps provided cover for refugees and the 1824 corrected list of estates and proprietors lists it as being planted in provisions, so there likely would have been food to steal. Maroon settlements would have provided a fragile community, one always at risk of discovery and destruction. One would expect those on estates near the coast to escape by boat, and it seems likely that some did, but the lists reveal quite a number who were captured further inland, as the lines indicate. With only a few exceptions, the locations in the interior are sites of capture rather than escape. The plantations that did exist would have likely been coffee or cacao, which can grow on uneven terrain.

Towns are also represented on the lists. St. George’s is the capital of Grenada, but there is also a plantation called St. George, and the capital is sometimes referred to as St. George. The slight spelling difference between the capital and the plantation may or may not be relevant. There were fifteen total runaways captured in St. George’s in 1819 and 1825. If we include those captured in St. George, where the list does not specify plantation, the list grows to 36. It seems likely that some fugitives were in the capital while others were discovered on the plantation. The same is likely true for Gouyave, which is also a plantation. Sixteen runaways were captured on or near Gouyave Estate, but perhaps some were actually in the town. Both St. George and Gouyave Estates are close to the towns. These were the most common places in which runaways were captured, after Perdmontems.

Where did the enslaved flee from? The lists of runaways and the map reveal which estates had the most marronage activity. Grand Ance Estate, which was on the southwestern coast, comes up eleven times, with the runaways discovered inland. One cannot help but wonder if more people escaped by the sea. The next estates with the most runaways were Hope Vale and Paradise with eight runaways; Telescope had seven. Telescope was just north of Grenville on a major harbour, so it is easy to imagine a runaway finding a small boat to use as a means of escape or finding work aboard a vessel.

While I have taken as true the information in these lists, it is also possible those captured gave false information. For example, the notice below appeared in the May 1819 St. George’s Chronicle in response to an apparent error in the March list of runaways. It refers to a woman who gave her name as Jacline and belonging to Lataste Estate, but captured on neighboring River Sallee Estate. William Greig, who was perhaps the manager of the Lataste plantation, claims no such person worked or who was captured on these estates.[16] Certainly a fugitive had incentive to lie to avoid punishment. But it is not clear what happened to those who were caught by the Loyal Rangers in such circumstances. I have found no follow up advertisements seeking to determine Jacline’s home. But perhaps her name was not even Jacline. Was she sold? Others appear to have been returned to their plantations. As with any archive, we have to cast a critical eye on our sources.

Figure 5: Notice, From St. George’s Chronicle, May 15, 1819.

For individuals listed, L. LaGrenade would refer to Louis LaGrenade II, son of a well-known and propertied free man of color who served the British with distinction as head of the militia of free people of color. According to LBS, he owned Morne Jaloux and Woburn Estates. Smith also lists him owning Mount Desir. It is unclear from Smith’s map where Woburn is, but a modern map shows it along what Smith labels as Court Bay, now Woburn Bay. Any runaways from L. La Grenade have been marked as coming from Morne Jaloux. The two estates appear to have been near one another. Mary Stroud is listed as claiming five runaways, the most for an individual on the list. Perhaps she was a particularly harsh mistress.

The inset map below shows the path of Bob, a man who escaped from F. La Barrie to Woodford Estate. With some searching, we find out that Francis La Barrie owned Point Saline and Bellevue estate. A Victor La Barrie – perhaps a brother or a cousin? – owned Woodford Estate.[17] One wonders if Bob and others who escaped from one plantation and were captured on another, were moved unwillingly between the estates and returned to visit family and friends. Did Bob travel by road or by boat along the coast?

Figure 6: Bob’s possible path

Legacies of Slavery on the Modern Map of Grenada

While the LBS database was useful for determining what parish an estate was in, it rarely included a map. To map the individual estates on the lists, I did internet searches that usually yielded modern maps of Grenada. More often than not, these old plantation names remain the names of towns and villages, or estates that have been converted into tourist destinations like Belmont Estate. When looking at the modern map of Grenada compared to the historical map, the legacies of plantation agriculture on the landscape are clear, from names of towns to names of rivers and bays. One sees the names of prominent French families from the colonial period and British governors and government officials. One imagines the descendants of these enslaved runaways walking some of the same roads and travelling the same currents as they trek from Grenville to St. George’s and other places on the island. Were well-worn paths created by runaways turned into roads?

By mapping marronage within Grenada we can see connections between parts of the island and plantations, just as we map mobility between different islands in the Lesser Antilles. Some may have been seeking freedom and others may have been visiting family and friends. We see surprises, such as people choosing to flee inland rather than by sea, or across the island. We try to imagine the dangerous journey through forests, along roads, or on the sea, but we cannot possibly imagine the anguish of being captured and returned to slavery.

Notes

[1] St. George’s Chronicle, and Grenada Gazette, May 13, April 28, December 15, 18, 1819, printed at St. George’s, Grenada, accessed through Caribbean Newspapers, Series 1, 1718-1876, Readex through the University of Copenhagen. There is also a list in February 11, 1826 covering August-December of 1825. All newspaper references from Caribbean Newspapers.

[2] August-November 1819=102 runaways; August-December 1825=47 runaways.

[3] March 15, 1815, St. George’s Chronicle, and Grenada Gazette.

[4] M. Pinel, Plan de l'Isle de la Grenade (London, 1763); Daniel Paterson, A new plan of the island of Grenada (London, 1780), “MapScholar,” accessed August 18, 2022, http://www.viseyes.org/mapscholar/?3216. “Map of the Island of Grenada Divided into Parishes and Including a Plan of The Harbour of St. George. Taken from an Actual Survey Made by Gavin Smith in the Year 1801 under the Authority of the Legislature of the Island.” by Gavin Smith. Map from the Map Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The map was accompanied by a list of proprietors, Reference to the Plan of the Island of Grenada (updated 1824). My thanks to Stephan Mullen for sharing Reference with me.

[5] For scholarship on marronage, see, for example David Barry Gaspar, Bondmen & Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua, with Implications for Colonial British America (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985); N. A. T. Hall, “Maritime Maroons: ‘Grand Marronage’ from the Danish West Indies,” The William and Mary Quarterly 42, no. 4 (1985): 476–98, https://doi.org/10.2307/1919030; Linda M. Rupert, “Marronage, Manumission and Maritime Trade in the Early Modern Caribbean,” Slavery & Abolition 30, no. 3 (September 1, 2009): 361–82, https://doi.org/10.1080/01440390903098003; Linda M. Rupert, “Seeking the Water of Baptism: Fugitive Slaves and Imperial Jurisdiction in the Early Modern Caribbean,” in Legal Pluralism and Empires. 1500-1850, ed. Richard J. Ross and Lauren Benton (New York, USA: New York University Press, 2020), 199–231, https://doi.org/10.18574/9780814708316-009; Price Richard, Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas, 2. ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979); Bernard Marshall, “Slave Resistance and White Reaction in the British Windward Islands 1763-1833,” Caribbean Quarterly 28, no. 3 (1982): 33–46. The September 2021 issue of Slavery & Abolition 24, no. 3 focuses on marronage.

[6] Rebecca Ginsburg, “Escaping through a Black Landscape,” in Cabin, Quarter, Plantation: Architecture and Landscapes of North American Slavery, eds. Clifton Ellis and Rebecca Ginsburg (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), 54.

[7] For more on Fedon’s Rebellion, see Edward Cox, “Fedon's Rebellion 1795-1796 The Journal of Negro History 67, no. 1 (Spring, 1982): 7-19; Timothy Ashby, “Fedon’s Rebellion,” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 62, no. 251 (Fall 1984): 155–68 and vol. 63, no. 256, 220-235; Kit Candlin, The Last Caribbean Frontier, 1795-1815 (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire : Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), ch. 1 and “The Role of the Enslaved in the ‘Fedon Rebellion’ of 1795,” Slavery & Abolition 39, no. 4 (October 2018): 685–707, https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2018.1464623; Caitlin Anderson, “Old Subjects, New Subjects and Non-Subjects: Silences and Subjecthood in Fedon’s Rebellion, Grenada, 1795-96,” 201-217; Tessa Murphy, “A Reassertion of Rights: Fedon’s Rebellion, Grenada, 1795-96,” La Révolution française, 14, 2018, Online since 18 June 2018, accessed 20 June 2018, DOI : 10.4000/lrf.2017.

[8] George Brizan, Grenada: Island of Conflict: From Amerindians to People's Revolution 1498-1979 (Bath: The Pitman Press, 1984), 96, 102.

[9] To the Editor of The Chronicle, St. George’s Chronicle, and Grenada Gazette, June 13, 1835. Before Fedon’s Rebellion, free people of color were typically mobilized to periodically track down runaways.

[10] CO 103/10/5, The National Archives, Kew, London, United Kingdom.

[11] Minutes of the Honourable the General Assembly of Grenada and its Dependencies, printed in St. George’s Chronicle, and Grenada Gazette, December 4, 1819.

[12] Accounts of the Legislative Assembly, St. George’s Chronicle, and Grenada Gazette, July 7, 1819; Brizan 80.

[13] Legacies of British Slavery Database,

[14] Legacies of British Slavery

[15] Nicholas Crawford. “Calamity’s Empire: Slavery, Scarcity, and the Political Economy of

Provisioning in the British Caribbean, C. 1775-1834” Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University,

Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, 2016. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/33840679. Sales of the estate also include both names. There is no information on this estate in Legacies beyond the slave compensation claim.

[16] May 15, 1819, St. George’s Chronicle, and Grenada Gazette.

[17] June 1819 list, published December 15, 1819.