Florentine's Letters: Grief, Sorrow, and Love from Martinique to Dominica

By Gunvor Simonsen.

On 1 March 1818, the enslaved woman Florentine was carried away from Dominica to Martinique by her enslaver, a certain Mr. Thomas Hugh Fergusson. The purpose of the transfer was to sell Florentine on Martinique. Fergusson wanted to sell her, he claimed, because of her unruly character. Yet, reading through the paper trail of this episode of Antillean enslavement leaves the distinct impression that Fergusson was attempting to get some ready cash out of the troubled estate of the underage girl Eliza Dubocq, to whom he had recently been appointed guardian. There were many other claims on the estate, however. Selling Florentine on Martinique allowed Fergusson to evade opposition from other claimants who might question why he – and not they – should cash in on the estate’s extant assets.

In Martinique, Florentine was bought by Madam Letang. Somehow, however, Florentine managed to return to Dominica. She arrived in mid-April 1818 aboard the sloop Spring, mastered by one George Burton, who we know from other cases in the Vice Admiralty court was deeply involved in trafficking enslaved people between the two islands. Upon arrival, Florentine was seized by Dominica’s custom controller, Mr. Symond Bridgwater. He believed Fergusson had acted contrary to the laws abolishing the slave trade. Florentine ought to be forfeited to the crown and subsequently freed. The Vice Admiralty Court at Dominica concurred. On 16 May 1818, Vice-Admiralty Judge Archibald Gloster pronounced Florentine to be “illegally sold at Martinique” and therefore to be “forfeited for the sole use of His Majesty.”

Map showing the location of Dominica and Martinique in the Lesser Antilles (Credit: Gunvor Simonsen, Ping Chang, and Rasmus Christensen).

While Dominican and Martinican enslavers - the owners of enslaved people, the legal officers invested in adjudicating slave trials, and the governors tasked with maintaining slavery - fought over Florentine’s fate, she took matters into her own hands and obtained passage home. Perhaps she knew that the new laws abolishing the slave trade gave her a shot at freedom.

Legal ingenuity, however, was not the only recourse available to Florentine. She also had family. In two letters, extant in translation, probably originally written in French or French Creole, Florentine reached out from her new position as an enslaved woman in Martinique to her mother and aunt on Dominica. These older women were presumably enslaved as well.

We cannot know with certainty that Florentine wrote rather than dictated the two letters, but their dates suggest that Florentine was in fact their author. The first letter was dated only two days after her arrival on Martinique and the second letter was written shortly after she was moved from St. Pierre to Nouvelle Cité. Indeed, it seems that Florentine did not depend on others for keeping up her written correspondence. Perhaps her mother and aunt had taught to read and write.

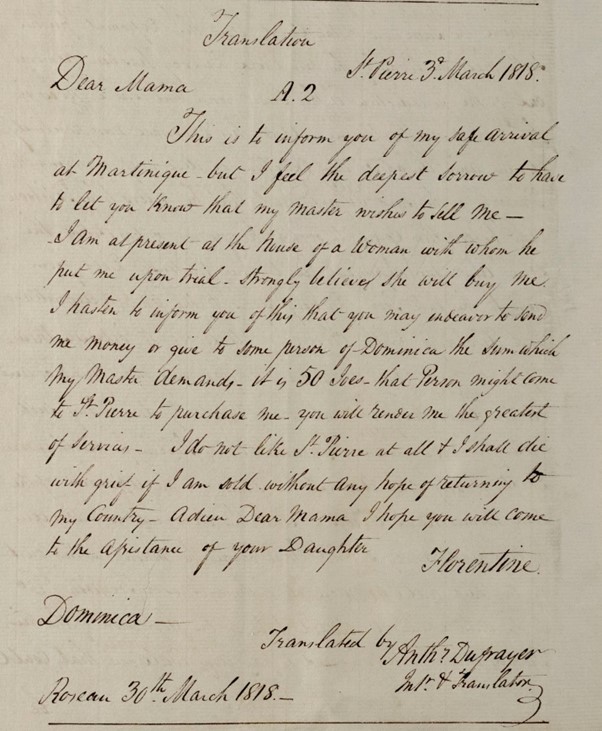

Letter by Florentine to her Mama, St. Pierre, 3 March 1818 (British National Archives, CO 71/55, Dominica 1818 - Governor Maxwell: Despatches).

In her letters, Florentine spoke of her sale in a deeply emotional tone. In the first letter, written on 3 March 1818, she said, “I feel the deepest Sorrow to have to let you Know that my Master wishes to Sell me […] & I shall die with grief, if I am sold without any hope of returning to my Country.” Concluding her letter, Florentine begged for her mother’s help: “Adieu Dear Mama I hope you come to the Assistance of your Daughter.” In the letter, Florentine also asked her mother to send money. She wanted to go back to Dominica, stating “I do not like St Pierre”.

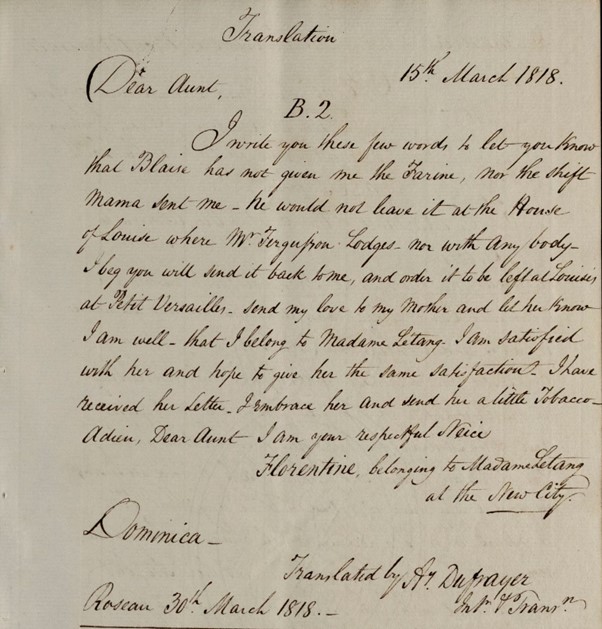

Two weeks later, on 15 March 1818, Florentine addressed her aunt, making sure to inform her of her new owner and location. Florentine has been moved, it appears, from St. Pierre to Nouvelle Cité. This letter shows that Florentine received both material support and emotional comfort from her Dominican female relatives, in particular from her mother. Florentine explains to her aunt where flour should be delivered for her to receive it, and she notes that the “shift mama sent me” had not arrived.

Letter by Florentine to her Aunt, 15 March 1818 (British National Archives, CO 71/55, Dominica 1818 - Governor Maxwell: Despatches).

Concluding her letter, Florentine asked her aunt to “[s]end my love to my Mother and let her know I am well.” Indeed, mother and daughter had already established a longer correspondence. Florentine has received, she notes, her mother’s letter, and now she sends back an epistolary hug and “a little Tobacco.”

Family ties crossed Antillean waters. They allowed Florentine to receive the help of her maternal family. Upon her return, the three women joined forces as they sought to attain freedom for Florentine. The very fact that her letters had found their way into paper archive of the Vice Admiralty Court suggests that the women were aware of the legal opportunities that anti-slave trade legislation had brought to Dominica. Together, they presumably decided that these letters could make Florentine’s case stronger, and indeed, in the information filed against Fergusson by Domnica’s custom officers, Florentine’s letters were central.

We cannot know how Florentine’s mother and aunt helped her return to Dominica, such dangerous information was not put into writing. The women must have communicated in other ways as well. Perhaps trusted couriers helped them agree on an escape plan. Yet her letters describe the material support, the food, clothing, and cash that the women exchanged, and the emotional support they sustained despite being apart. The power of their connection must be reckoned with as we attempt to fill the gaps of an archive that very often effaces or misrepresents the experiences of enslaved women. While most enslaved women did not communicate in writing, Florentine’s letters show us an intimate and emotional history of slavery, a history in which family ties allowed women in bondage to counter grief and sorrow.