Newspapers as Microcosms of Everyday Life for Elites in the Danish West Indies

By Gabriëlle La Croix.

For almost three years, the entire ITSS team has been diligently reviewing Caribbean newspapers for our database. While our primary focus has been on identifying notices of enslaved individuals who absconded, we have also uncovered other intriguing and noteworthy articles that provide insights into daily life on these small islands. Besides relaying information from Europe or from elsewhere in the Americas, newspapers were filled with personal notices of sale, death, and marriage as well as announcements and the occasional entertainment piece.

Newspapers were often locally printed on the islands. The printing press was initially introduced to the Caribbean in the early eighteenth century, representing a pivotal advancement in the region's communication. Initially, many of these printing presses were under government control, as authorities sought to manage the flow of information. However, other presses emerged from the entrepreneurial efforts of private businesses, highlighting a growing interest in commercial publishing. These newspapers, regardless of their origins, typically addressed similar themes, reflecting the shared interests of both their printers and readers. Major topics included the institution of slavery, a fundamental aspect of Caribbean society and economy, and the cultivation and trade of sugar, the region's primary cash crop. Moreover, international relations were also of significant concern, particularly in relation to immigration, which affected demographic shifts and social dynamics within the islands. Consequently, these newspapers not only served as vehicles for information but also as platforms for public discourse on the pressing issues of the time.[1]

The examples below are drawn from the Royal Danish American Gazette, which was published on St. Croix during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (1770-1802). This newspaper was predominantly in English, and occasionally in Dutch and Danish, reflecting the languages most commonly spoken across the island. After the newspaper ceased to exist, its place was taken by the St. Croix Gazette (1808-1813). The Danish West Indies had a total of 11 newspapers over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (most of them published on St. Croix), of which the Royal Danish American Gazette was probably the first.

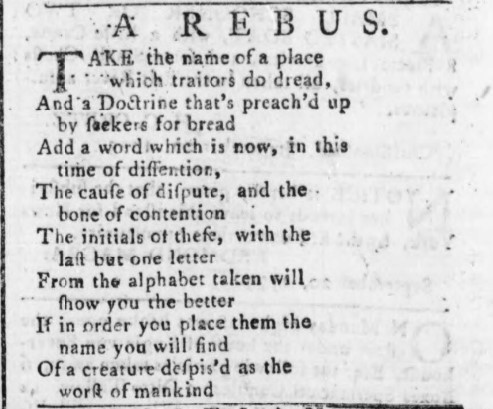

Figure 1: A Rebus, The Royal Danish American Gazette, 20-09-1775 (Mediestream).

Figure 1: A Rebus, The Royal Danish American Gazette, 20-09-1775 (Mediestream).

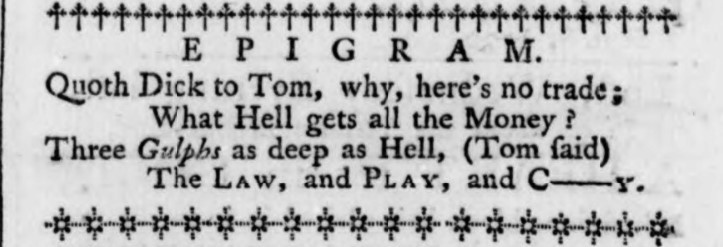

In the newspaper published on September 20, 1775, a rebus was featured (see Figure 1)[2]. It was not unusual for printers of that era to include puzzles in their publications. However, this particular rebus stands apart from modern puzzles and other contemporary rebuses, which typically utilize images to suggest the intended words. Even though this type of puzzle had existed since ancient Roman and Greek times, the rebus was popularized in France during the late Middle Ages before spreading to other European nations and, as this newspaper illustrates, eventually reaching the Caribbean.[3] Additionally, the puzzle is explicitly aimed at a specific segment of society—those who were literate, relatively educated, and of a certain social standing. This again tells us that newspapers were more than informational; the printer was also focused on replicating European customs to its readership. Another example of a play on words can be found in Figure 2, which shows a short epigram. Epigrams are brief, often satirical statements that express an idea in an entertaining way.[4] They are often written to “hit home, to wound”, not unlike a traditional satire.[5]

Figure 2: Epigram, The Royal Danish American Gazette, 08-09-1770 (Mediestream).

Figure 2: Epigram, The Royal Danish American Gazette, 08-09-1770 (Mediestream).

Other sections frequently found amongst the news articles and advertisements included reflections on various topics. Many of these pieces are unattributed and appear to be published at the printer’s discretion, leaving the authorship uncertain. The Gazette was printed by Daniel Thibou, who resided in Christiansted, adjacent to the printing office. Little is known about Thibou’s life, although he is believed to have originally come from St. Kitts before settling on St. Croix and opening the first print shop in 1769.[6] Thibou was not the only printer who seemed to have originated from St. Kitts, as by the 1790s the printer of St. Eustatius, Edward Luther Low, had arrived from St. Kitts as well. He had been the King’s printer there and according to Maritza Coomans-Eustatia it is likely that he had already been doing printing work for St. Eustatius in the years before his arrival.[7] In the Dutch Leeward Islands and the Danish West Indies, it was common to find English printers. In contrast, most printers on the French islands were French, while in other Dutch colonies in the Americas, such as Suriname, the printers were Dutch.[8]

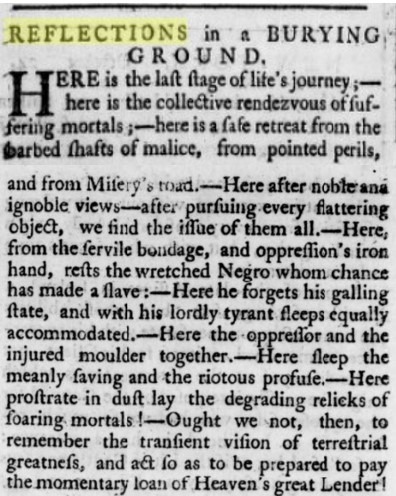

Figure 3: Reflections in a Burying Ground, The Royal Danish American Gazette, 09-01-1790 (Mediestream).

Figure 3: Reflections in a Burying Ground, The Royal Danish American Gazette, 09-01-1790 (Mediestream).

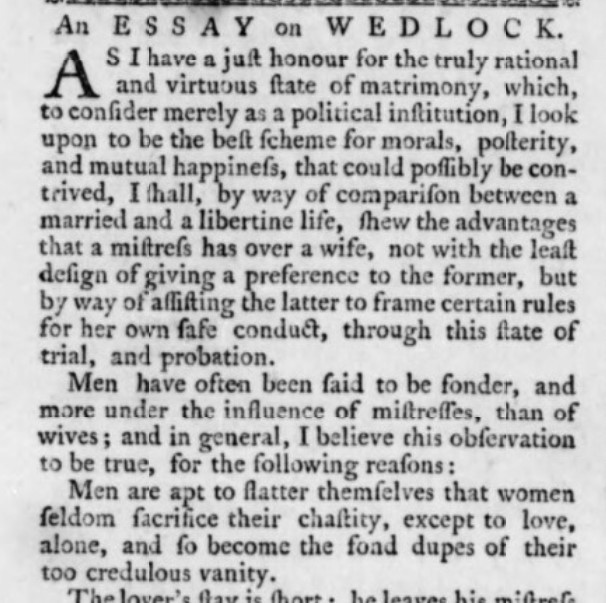

Figure 4: Extract of An Essay on Wedlock, The Royal Danish American Gazette, 01-08-1770 (Mediestream).

Figure 4: Extract of An Essay on Wedlock, The Royal Danish American Gazette, 01-08-1770 (Mediestream).

Common themes in these reflections encompass marriage, the social roles of men and women, and occasionally, death. Given that the colonial Caribbean experienced significant wars, natural disasters, and demographic challenges related to a scarcity of women, it is not surprising that individuals would contemplate these issues. Additionally, these reflections often incorporate religious elements, with references to "Heaven", or an "Amen" concluding the thoughts expressed.[9] Figure 3 (above) shows reflections on those who had been enslaved, suggesting to the reader that enslaved people and their enslavers lay side by side in the burying ground.[10] Whether in practice this was the case remains doubtful, as enslaved people were often buried separate from their enslavers. Figure 4 presents an excerpt from an essay discussing wedlock, or the state of being married. The author clearly advocates for traditional marriage and seeks to persuade both men and potentially women that this is the optimal choice for "posterity and mutual happiness."[11] This reflection points towards the importance of marriage in everyday life in the Caribbean, for men marriage would not only provide them a wife to mother legitimate offspring but it might also broaden their trading, and political connections, occasionally aiding them to rise in status.[12]

These examples collectively illustrate that newspapers from the colonial era served various roles beyond reporting on trade and monetary concerns. They provided insight into the lives of everyday people, highlighting aspects of daily existence that catered to the community's need for entertainment and engagement. In addition to advertisements for the return of fugitives to slavery and to financial matters, these publications reflected the societal interests and values of the time, offering stories, local events, and anecdotes that shaped the public's understanding of their world. This blend of commercial content and reflections on ordinary life demonstrates the newspapers' function as a vital source of information and social cohesion, capturing the nuances of daily life and the interests of the community.

[1] Roderick Cave, “Early Printing and the Book Trade in the West Indies,” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 48, no. 2 (1978): 168, 190.

[2] “Rebus,” The Royal Danish American Gazette, September 20, 1775, VI, 811 edition.

[3] Marcel Danesi, The Puzzle Instinct: The Meaning of Puzzles in Human Life, 1st ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), 60.

[4] “Epigram,” The Royal Danish American Gazette, September 8, 1770, I, 19 edition.

[5] Salvatore I Attardo, Encyclopedia of Humor Studies, 1st ed., vol. 2 (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Incorporated, 2014), 213, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483346182.

[6] Jens Vibæk, "Dansk Vestindien 1755-1848, Vestindiens Storhedstid", in Vore Gamle Tropekolonier Volume 2, ed. Johannes Brøndsted (Copenhagen: Westermanns Forlag, 1953).

[7] Maritza Coomans-Eustatia, “Notes on Early Printing in the Dutch Caribbean Islands,” in History of Literature in the Caribbean, Volume 2: English- and Dutch-Speaking Regions, ed. A. J. Arnold (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2001), 368.

[8] Cave, “Early Printing and the Book Trade in the West Indies,” 173.

[9] “The Husband’s Creed,” The Royal Danish American Gazette, August 4, 1770, I, 9 edition.

[10] “Reflections in a Burying Ground,” The Royal Danish American Gazette, January 9, 1790, XX, 2401 edition.

[11] “An Essay on Wedlock,” The Royal Danish American Gazette, August 1, 1770, I, 8 edition.

[12] Rebecca Hartkopf Schloss, “Furthering Their Family Interests: Women, French Colonial Households, and Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic,” Early American Studies 20, no. 1 (2022): 1, https://doi.org/10.1353/eam.2022.0000.