PhD Fellow Rasmus Christensen's Work on ITSS Database

By Rasmus Christensen.

This semester, I have been on a break from my PhD research and have worked as a research assistant on the IN THE SAME SEA project to finish the project’s database on enslaved fugitives in the Lesser Antilles, which we started work on approximately 2.5 years ago. All the members of ITSS have spent hundreds of hours flipping through thousands of colonial newspaper issues to locate notices of enslaved people running away or enslaved people imprisoned in colonial prisons (which we have decided to term 'jail lists'). Thanks to the large digitized newspaper collections available online, we have been able to search through issues of more than 50 different colonial newspapers from St. Thomas in the north, to Trinidad in the south, and Curaçao in the west, covering the period from 1765 to 1863.

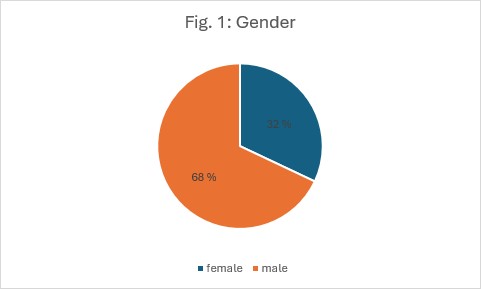

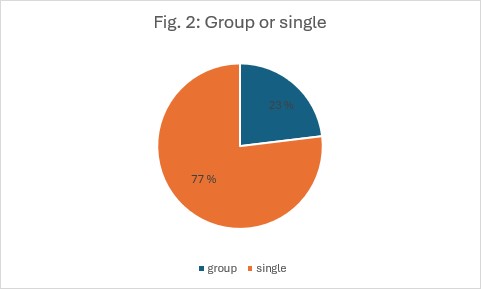

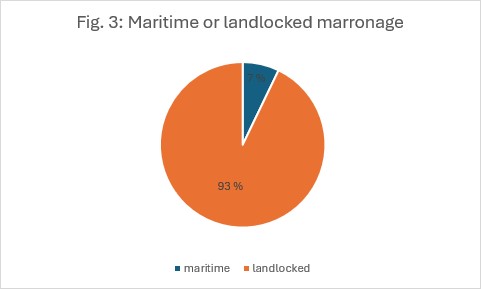

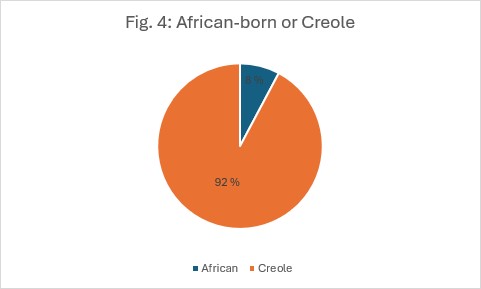

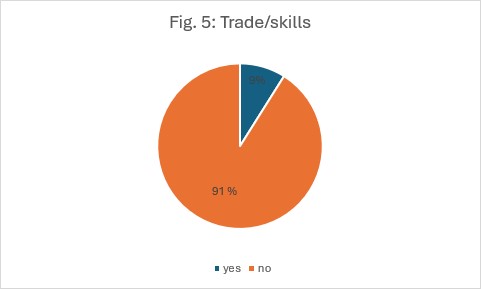

We are at the end stage of entering into the database, and have 3935 notices and jail-lists, containing information on 7022 fugitive individuals (for some overall information on these individuals, see figures 1-5).

Figure 1: Gender division in the fugitive database.

Figure 1: Gender division in the fugitive database.

Figure 2: Group marronage vs. single individuals in the database.

Figure 2: Group marronage vs. single individuals in the database.

Figure 3: Maritime vs. landlocked marronage in the database.

Figure 3: Maritime vs. landlocked marronage in the database.

Figure 4: African vs. Creole individuals in the database.

Figure 4: African vs. Creole individuals in the database.

Figure 5: Mention of trade/skills in adverts in the database.

Figure 5: Mention of trade/skills in adverts in the database.

When we designed the database, we decided on a limited number of attributes that we would enter for each individual based on some of the research questions we wanted to ask and because we knew that we would not have time to enter all the information provided in the notices. Because of this, we decided that it was important to transcribe the complete text of all the notices, facilitating use of the database in future research projects. The complete transcriptions will make it easier for other scholars with different interests and questions to search and organize the data for their own purpose.

My tasks in the previous months have been to ensure consistency, review incomplete entries, and coordinate the entering of the transcriptions. During this process, we have used the HTR software Transkribus to read the images of the notices. This has speeded up the process of entering transcriptions, even though the machine-read notices needed to be reviewed manually because of imperfect transcriptions.

Working with the database has spurred many questions within the ITSS team about the nature of the notices and jail lists as historical sources, and about what they can tell of the historical reality: is the demographic profile in the data representative of the phenomenon of marronage as a whole, or are there blank spots in the material that we can only elucidate by using other types of records? What kind of control mechanisms do the notices represent, how do these change over time, and for what reason? Since we have not yet finished the database, we have not yet tried to answer these questions, but we look forward to doing it when the data are published.

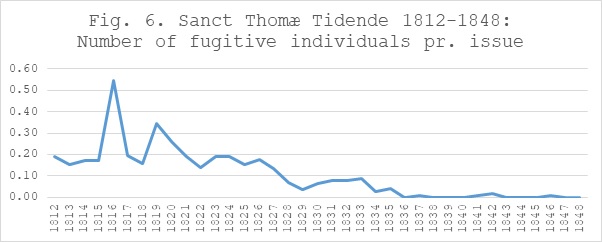

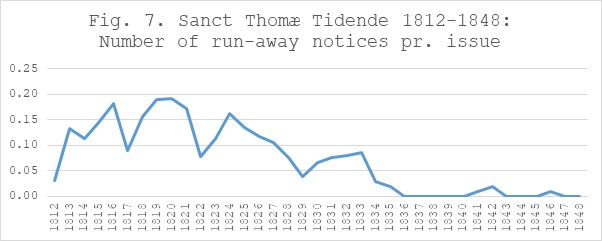

One example is from the newspaper Sanct Thomæ Tidende (or The Saint Thomas Gazette) from the island of St. Thomas in the former Danish West Indies, today the US Virgin Islands. This newspaper was consistently published from 1809 to 1917, although some issues do not survive. For this database, we have been concerned only with the period under slavery, which ended in July 1848 on St. Thomas.

Figure 6: Number of fugitives per issue of a newspaper from St. Thomas between 1812 and 1848.

Figure 6: Number of fugitives per issue of a newspaper from St. Thomas between 1812 and 1848.

Figure 7: Number of newspaper ads in a St. Thomas newspaper between 1812 and 1848.

Figure 7: Number of newspaper ads in a St. Thomas newspaper between 1812 and 1848.

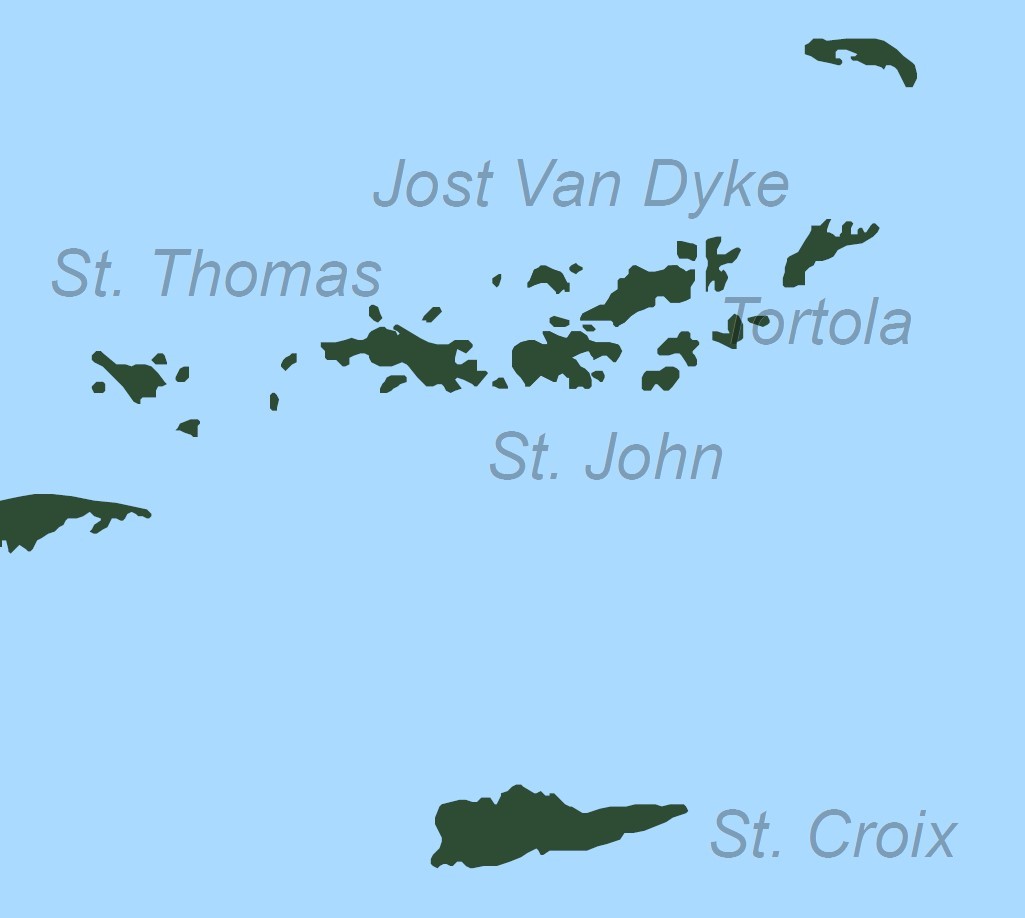

The graphs above show the number of enslaved fugitives per newspaper issue (fig. 6) and the number of run-away advertisements per issue (fig. 7). In this way, we can see how many enslaved fugitives were announced throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, as well as how often advertisements were used to announce enslaved people on the run to the public. On the face of it, the data suggest a decline in fugitives throughout the period. However, this seems incorrect when we put it into the larger historical context of political developments in this period. Because of the British Consolidated Slave Trade Act of 1824 and the British abolition of slavery in 1834, enslaved people in the Danish West Indies would have gained greater opportunities for escaping slavery by fleeing to the nearby British Virgin Islands. This, we know, increased maritime escape attempts across the Danish/British border and led to a fundamental anxiety among slaveowners and governmental officials in the Danish West Indies. This development, however, is not evident from the data in the newspapers. Maybe this discrepancy can be explained by a change in the manner of publicly announcing the escapes of enslaved people. This change made, for the most part, run-away advertisements obsolete. While we still need to examine this further, one explanation could be that during this period, marronage went from being a private matter of the single slave owner to becoming a public matter on a larger scale because of the new legal landscape that threatened the stability of the Danish slave society.

Figure 8: Map showing the US Virgin Islands (former Danish West Indies) and the British Virgin Islands.

Figure 8: Map showing the US Virgin Islands (former Danish West Indies) and the British Virgin Islands.

When the last transcriptions have been entered and the last revisions made, the next step will be to make the database ready for publication. The data will be available online together with an interactive map to help visualize the data. We look forward to presenting and publishing the data and sharing it with you. We hope it will prompt a lot of interest in and discussions about marronage in the Lesser Antilles in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Figure 9: Database dashboard for entry of the transcriptions by the ITSS team.

Figure 9: Database dashboard for entry of the transcriptions by the ITSS team.