Splashes in the Antillean Archives

By Rasmus Christensen.

The island colonies of the Lesser Antilles were resource-scarce societies. As cotton and sugar production took off during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the islands came to house a population that could not be fed entirely on locally produced crops. Islanders, in particular enslaved people, depended on the regular import of flour and salted provisions such as beef and herring from North America and Europe, but they also turned towards local resources. These included crops grown on provision grounds and the fruits of the sea.

As part of my PhD research, I have started to look into the archives of the British, Danish, and Dutch empires to find out what colonial authorities thought about the resources of the waters surrounding the Lesser Antilles. I want to understand how they construed marine resources and their value within colonial society. I am particularly searching for references to edible marine resources, first and foremost fish. While the importance of imported fish such as salted cod and pickled herring is well documented in the historiography, colonists’ engagement with their marine environment is much less explored.[i] Correspondence concerning these imported commodities figures regularly in the archives, but in my search, I am looking for fish caught locally.

Turning the pages of this or that colonial correspondence, it appears as if marine resources were absent from the islands; as if, you are looking out over the sea searching for life beneath the surface. At first glance, it appears to be completely silent and almost dead. But, if you hold your breath, have patience, and watch carefully, suddenly a single disturbance will appear followed by another and yet another and you will soon be able to recognize all the action taking place beneath the surface. Like fish splashing on the surface, hints about marine resources appear here and there in the colonial archives.

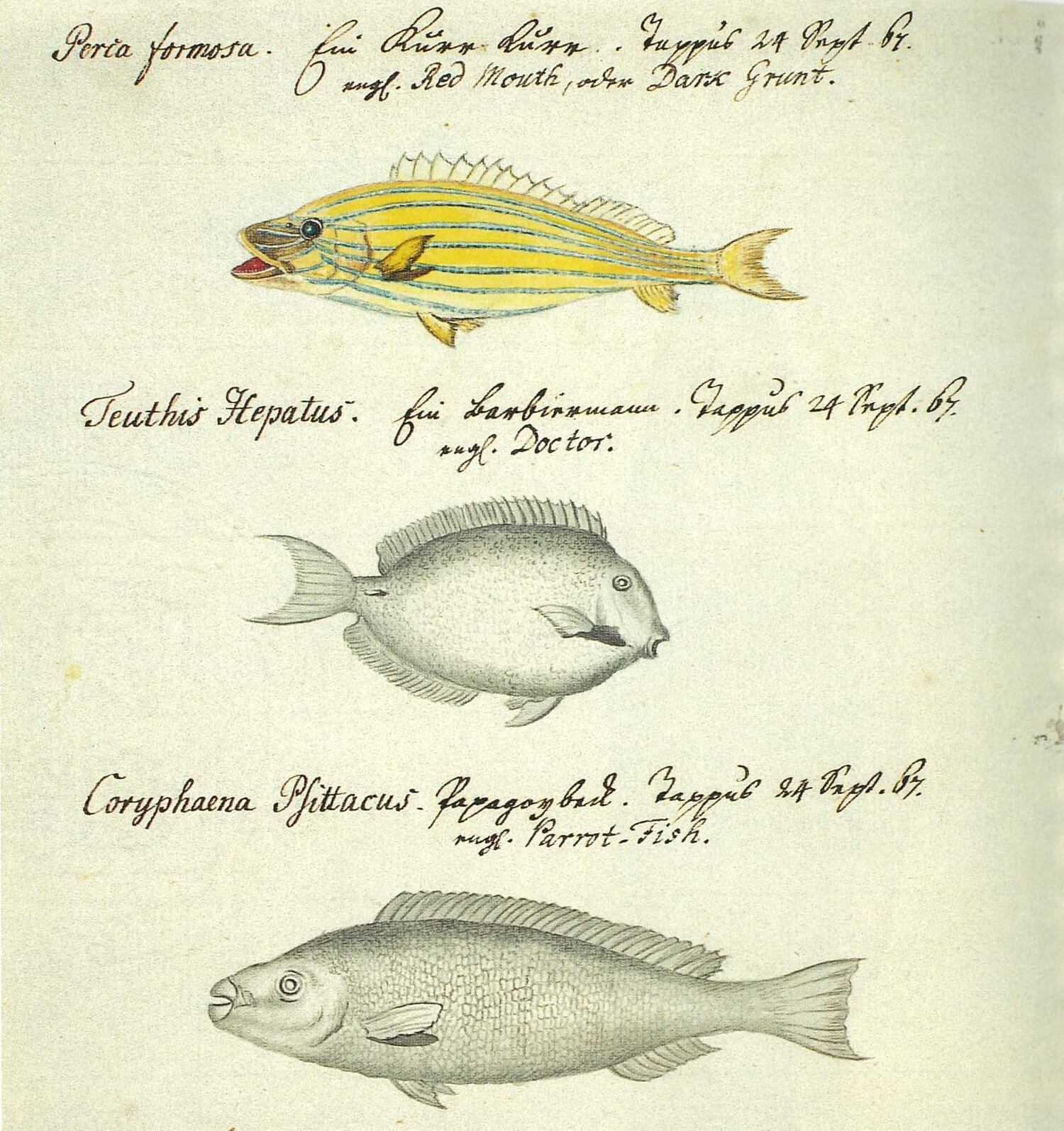

Figure 1. Illustration of various fish. From C.G.A. Oldendorps Historie der caribischen Inseln Sanct Thomas, Sanct Crux und Sanct Jan, Erster Teil, III, 1777.

Figure 1. Illustration of various fish. From C.G.A. Oldendorps Historie der caribischen Inseln Sanct Thomas, Sanct Crux und Sanct Jan, Erster Teil, III, 1777.

The evidence for use of local marine resources in the archives is indeed very scattered. It is easy to reach the conclusion that the lack of fish in the archives reflects a reality in which local marine resources did not matter. Instead, I would argue that it hints at a profound bias in the archival record in which export crops and imported foodstuff, being inseparable parts of the colonial economic machinery, were favored at the expense of goods of a more “quotidian” nature. While imports were taxed, providing revenue for colonial institutions, fish, turtle, and other local marine resources escaped the fiscal logic of the European colonial states. Local marine resources therefore only rarely entered into the minds of colonial officials. As historian Keith Pluymers has noted for the case of wood in the British colonies:

"Woods had value for their capacity to meet local needs, but, as in Bermuda, it was those trees with the capacity to serve transatlantic markets that registered most prominently in surviving property records. Much like the Bermuda palmetto, the patterns and rules that colonists developed for everyday and local uses fall largely outside the scope of surviving records.”[ii]

Indeed some records suggest that one should not take the limited evidence in the archives at face value. Various local ordinances from the British, Danish, and Dutch colonial authorities testify to concerns about sustaining marine resources. In Antigua, for example, the Assembly passed “An Act to prevent Abuses in the Fishery about this Island.” The motivation for the legislative measure was that “the Fishery … hath been greatly injured of late Years by the too frequent Use of Nets or Seins of too small a Mesh, to the great Destruction of young Fish or Fry.”[iii] While I still have to dive deeper into the circumstances underlying this and other similar acts, it is clear that there was in fact a local governmental engagement with marine resources and a recognition of their importance within the colonial society.

Contemporary visual records and narratives also tell a different story in their rendering of local marine life and its exploitation. Various engravings and paintings as well as written accounts reveal a great interest in fish and human engagement with the marine surroundings. This is especially manifest in the Dissertation sur les Pesches des Antilles written by an anonymous author in 1776.[iv] The dissertation mostly describes various Indigenous Caribbean and African fishing techniques but also provides glimpses of cultural practices connected to fishing, for example:

As far as one sees the pirogue arrive, the Negroes and Negresses, with baskets in their hands and with money, come running from all sides to buy fish. They themselves announces their arrival by the repeating sounds of a horn of lambis so that those who are in there [on land] are all the happier to resound that their fishing was more fruitful.

Charity, this amiable virtue too little exercised among the common people, is in great honor among this slave people. Rarely does one who has neither money nor money to buy the fish necessary for his subsistence return empty-handed.[v]

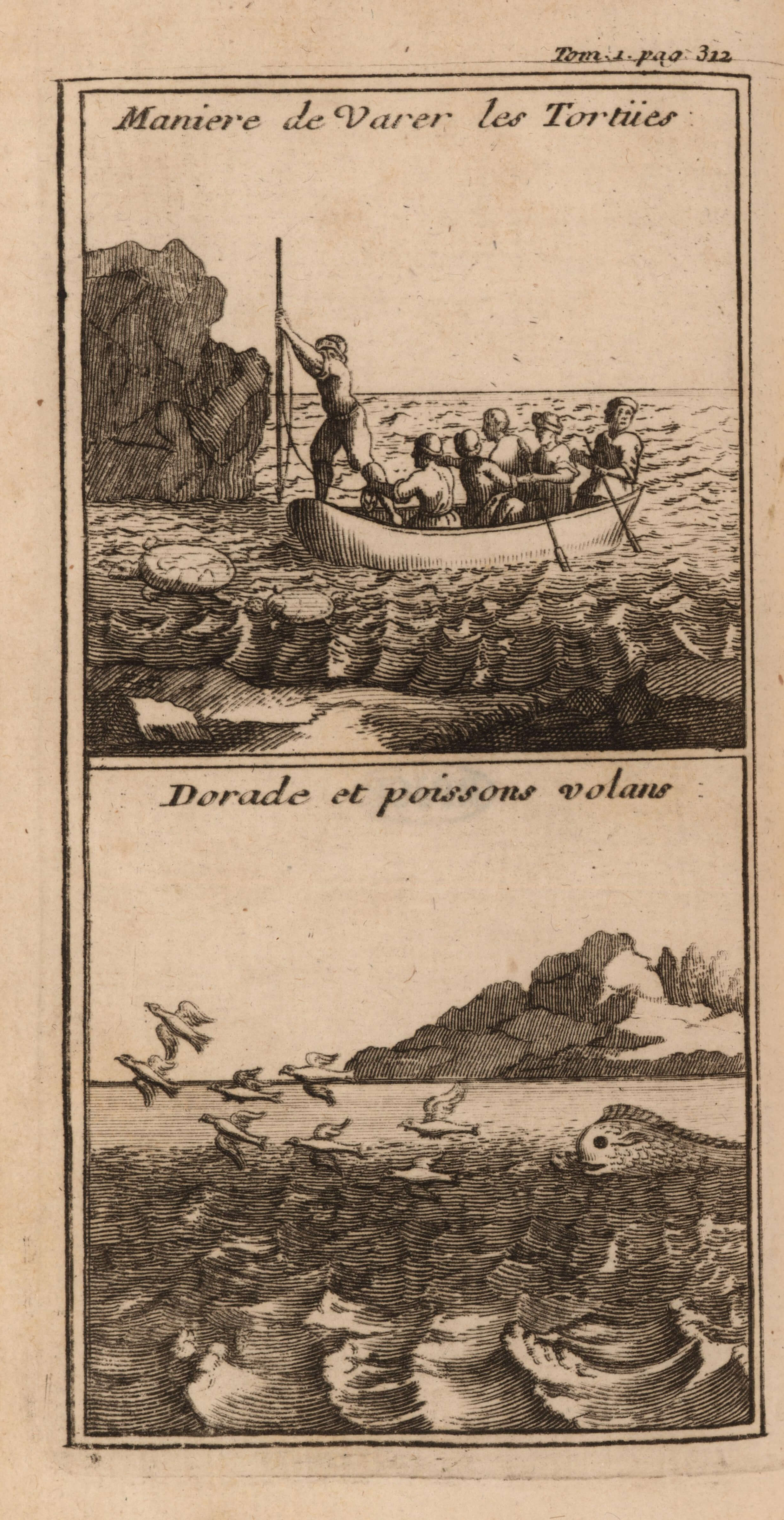

Figure 2. Turtle catching and fish. Jean Baptiste Labat, Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l’Amerique vol. 1, p. 312 (1722). © John Carter Brown Library.

Figure 2. Turtle catching and fish. Jean Baptiste Labat, Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l’Amerique vol. 1, p. 312 (1722). © John Carter Brown Library.

However, some records also reveal that colonial authorities had limited knowledge of fishing activities in local waters. In an 1826 revenue return from Grenada, colonial authorities estimate that 120 boats are engaged in the local fisheries. The assessed annual total catch is 469,400 lbs ascribing to the industry an annual value of £ 23,475.[vi] These estimates are based on information “collected from the most experienced persons in such matters,” since “[t]here are no regular Fisheries in the Colony, nor […] any means of ascertaining either the exact Number of Boats & Canoes employed wholly or partially in Catching Fish […].” The fish caught were “Jacks, King Fish, Snappers and a great variety of other Tropical Fish.” This statement is quite revealing of the ambivalent role of marine resources within the colony of Grenada and speaks to the limited presence of the topic in colonial archives in general. Even though considerable fishing activities were taking place within and around the colony, colonial authorities had no structured way of obtaining information about it. Maybe it was not a “regular” industry in the view of colonial officials, but it was still very much present in the everyday lives of ordinary people.

Figure 3. An engraving of a carangue or jack, from Jean Baptiste Labat's Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l’Amerique vol. 8, p. 312 (1722). © John Carter Brown Library.

Figure 3. An engraving of a carangue or jack, from Jean Baptiste Labat's Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l’Amerique vol. 8, p. 312 (1722). © John Carter Brown Library.

Fish also pop up on other occasions when they are enmeshed in questions of property rights. After the British conquest of the French part of St. Christopher in the 1690s, French plantations were handed over to British subjects. The patent issued by Christopher Codrington on November 24, 1696, stated that along “[…] Houses, Edificies, Buildings, […] Pastures, […] Woods, […] Canes, Corne, with the Soile, and ground of the Same,” “waters water courses fishing and fishing places with all other profits […]” belonged to the property of the owner.[vii] That fishing is mentioned in this context tells us a great deal about how it figured in the local economy, namely that fishing rights could be considered part of private property and that fish were seen as offering potential for economic gain.[viii]

As the above examples suggest, there was actually something going on with local marine resources within the colonies of the Lesser Antilles, something to bale out of the archives. I have yet to make the big catches … but I am sure they will come.

[i] Richard Price, “Caribbean Fishing and Fishermen: A Historical Sketch,” American Anthropologist 68, no. 6 (1966): 1363–83; Pedro Welch, “Exploring the Marine Plantation: An Historical Investigation of the Barbados Fishing Industry,” The Journal of Caribbean History 39, no. 1 (2005): 19-37; Julio A. Baisre, “Setting a Baseline for Caribbean Fisheries,” The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 5, no. 1 (April 16, 2010): 120–47; John M. Chenoweth, “Marine Shell and Small-Island Slavery in the Caribbean,” Historical Archaeology 52, no. 2 (June 1, 2018): 467–88. Indeed, the most recent environmental history of the Caribbean devotes only a couple of pages to the exploitation of marine resource in colonial times, see Philip D. Morgan, John R. McNeill, Matthew Mulcahy & Stuart B. Schwartz, Sea and Land. An Environmental History of the Caribbean (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 117-119.

[ii] Keith Pluymers, No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 176–78.

[iii] An Act to prevent Abuses in the Fishery about this Island (18 Nov 1765) published in The Laws of the Island of Antigua vol 1, 1805, 335. For Danish and Dutch examples see: Plakat ang. Fiskenettene hvorledes de skal være bundne, samt forbud at kaste giftig Træe i Vandene (https://www.sa.dk/ao-soegesider/da/billedviser?epid=20193436#284717,55588739); and: Ordonnantie. Prijzen van vlees en vis (24 Oct. 1783) published in Jacob Adriaan Schiltkamp and Jacobus Thomas de Smidt, eds., West Indisch plakaatboek 3: Nederlandse Antillen Bovenwinden: publikaties en andere wetten betrekking hebbende op St. Maarten, St. Eustatius, Saba 1648/1681-1816 (Amsterdam: Emmering, 1979), 320.

[iv] Anonymous, Dissertation Sur Les Pesches Des Antilles (1776), ed. Jean Benoist (St. Jacques: Centre de recherches caraïbes, 1975). See also fx. Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (London: Printed for Humphrey Moseley, 1657), fx. 35-36, 39. Jean Baptiste Labat, Nouveau voyage aux isles de l’Amerique vol. 1 (Paris: Rue S. Jacques, chez Pierre-François Giffart, près la ruë des Mathurins, à l’image Sainte Therese, 1722), 311, 325; Schmidt Johan Christian, Various Remarks Collected on and about the Island of St. Croix in America, Documentary Sources in Danish West Indian and U.S. Virgin Islands History (St. Croix: Virgin Islands Humanities Council, 1998), 25. For other examples see the IN THE SAME SEA working paper “Fishing and natural resources in 18th-century Danish West Indies” (https://inthesamesea.ku.dk/blog/fishing-and-natural-resources-in-eighteenth-century-danish-west-indies/).

[v] “Du plus loin que l'on voit arriver la pirogue de saine, les Nègres et les Négresses un panier à la main avec des effets ou de l'argent accourent de toutes parts pour acheter de poisson. Elle annonce elle-même son arrivée par les sons redoublés d'une corne de lambis que ceux qui sont dedans font d'autant plus volontiers retentir que leur pesche a été plus fructueuse. La charité, cette vertu aimable trop peu exercée parmi le commun des hommes est en grand honneur parmi ce peuple esclave. Rarement celui qui n'a ni argent, ni effêt pour acheter le poisson nécéssaire pour sa subsistance, retourne les mains vides,” Anonymous, Dissertation Sur Les Pesches Des Antilles, 26-27.

[vi] CO 318/106, “Brown Books of Statistical Tables, Grenada-Trinidad.” Equaling a purchasing power of a little below £ 1,600,000 in 2017. The 2017-value is calculated from British National Archives’ currency converter: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/.

[vii] CO 152/11.

[viii] Similarly, a patent to Cockrane Island off Antigua in 1733, included the rights to nearby fisheries, CO 152/43.