Vessel Itineraries in De Curaçaosche Courant: A Quantitative Microhistory, 1816-1818 and 1825-1826

By Felicia Fricke, Christian Kofoed Hansen, Hannah Hjorth, and Gunvor Simonsen

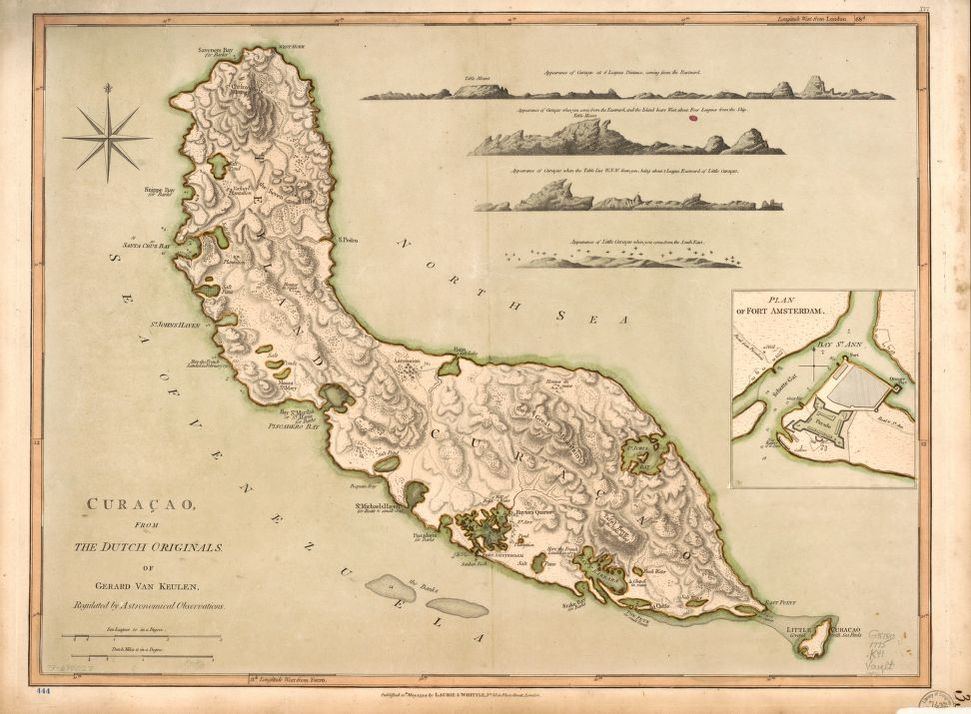

Figure 1: Van Keulen, Gerard, Robert Laurie, and James Whittle. Curaçao. London: Laurie & Whittle, 1794. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/73694027/

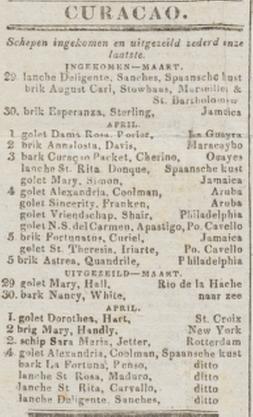

In 1812, a Scottish printer named William Lee arrived on the island of Curaçao. He printed the first issue of The Curaçao Gazette and Commercial Advertiser on December 11, 1812, under British rule and after the Dutch takeover of Curaçao in 1816 he stayed and continued his business. The new Governor, Albert Kikkert, appointed Lee as the King’s Printer on March 29, 1816. His newspaper then received a new name — De Curaçaosche Courant.[1] It was a typical West Indian newspaper.[2] In De Curaçaosche Courant, Lee presented his readers with systematic recordings of incoming and outgoing vessels in shipping lists containing vessel names, captain names, vessel destinations, date of arrival or departure, and sometimes the flag that the vessel sailed under.[3] In this blog post, shipping lists in two two-year periods (April 5, 1816, to March 28, 1818, and January 8, 1825, to December 30, 1826), are used to illustrate the interisland trade connections between Curaçao, the rest of the Caribbean, the wider Americas, and Europe in the first decades of the nineteenth century. [4]

Figure 2: Shipping list, De Curaçaosche Courant, April 5, 1816. Available from www.delpher.nl

Curaçao as a Caribbean Entrepôt

In 1675, the Dutch opened the island Curaçao to free trade. It became a major Caribbean commercial centre frequently used by competing, and even warring, European imperial powers for the import and export of commodities. Its port of Willemstad evolved from a small naval base into a cosmopolitan maritime centre.[5] Owing to its proximity to the Spanish mainland and its excellent harbour, Willemstad soon became more than simply a node for loading and unloading of goods. Financial institutions were established, ships were built, repaired, bought and sold; and sailors enlisted for voyages to all parts of the Caribbean. These circumstances positioned Curaçao centrally in the links that connected islands in the Lesser Antilles to one another and the wider Atlantic world.[6]

Figure 3: 't Eÿland Curaçao, ao. 1800. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/99465330/

A Quantitative Analysis of Vessel Itineraries

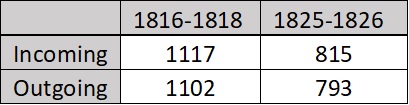

The data presented below represent a total of 3,827 vessel itineraries from or to Curaçao across four years (1,932 incoming and 1,895 outgoings) (see Table 1). This was an average of approximately 47 incoming and 46 outgoing vessels per month in 1816-1818; and 34 incoming and 33 outgoing vessels per month in 1825-1826.

Table 1: Incoming and outgoing vessel numbers for 1816-1818 and 1825-1826.

Incoming Vessels

Figure 4 (below) shows vessels coming into Willemstad (Curaçao) during the two selected periods. South America was the most common vessel origin across both periods, followed by the Lesser Antilles. Transatlantic connections made up only a fraction of the trade, with only 9 vessels entering from Amsterdam in 1816-1818 and 5 in 1825-1826. During the two periods, the proportion of trade links with the Greater and Lesser Antilles decreased, while the proportion of trade links with South and North America increased.

Figure 4: Origins of vessels coming into Willemstad (Curaçao) in 1816-1818 and 1825-1826.

Outgoing Vessels

Figure 5 (below) shows vessels leaving Willemstad (Curaçao) during 1816-1818 and 1825-1826. Again, South America was the most common vessel destination across both periods, followed by the Lesser Antilles. Transatlantic connections made up only a fraction of the trade, with 13 vessels leaving for Amsterdam in 1816-1818 and 9 in 1825-1826. The proportion of trade links with South America remained stable through time, while the proportion of trade links with the Lesser Antilles decreased and the proportion of trade links with North America increased.

Figure 5: Destinations of vessels departing from Willemstad (Curaçao) in 1816-1818 and 1825-1826.

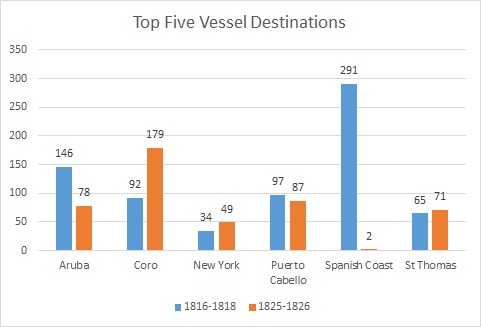

Destination Comparisons

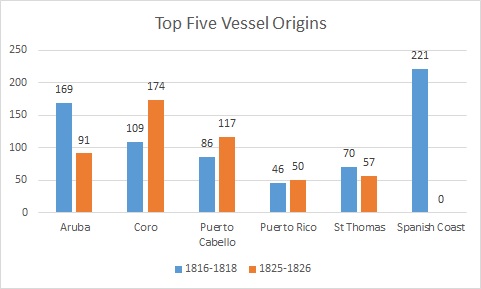

The top five most common origins and destinations for vessels recorded in De Curaçaosche Courant are shown in Figures 6 and 7 below. The large drop in involvement of the Spanish Coast category after 1816-1818 was probably due to increased accuracy of origin and destination recording in the later period.

Incoming trade relationships with Puerto Rico and St. Thomas stayed relatively stable across both periods. However, there were differences in incoming trade relationships with Aruba (decrease), and Coro and Puerto Cabello (increase). Outgoing trade relationships with New York, Puerto Cabello, and St Thomas remained relatively stable between 1816-1818 and 1825-1826, but there were differences in outgoing trade relationships with Aruba (decrease) and Coro (increase).

Figure 6: Comparison of top five vessel origins across both periods in 1816-1818 and 1825-1826.

Figure 7: Comparison of top five vessel destinations across all periods in 1816-1818 and 1825-1826.

Shifting Regional Patterns in Curaçaoan Trade

Though Curaçao had direct transatlantic commercial ties reaching several major European ports such as Liverpool and Rotterdam, these long-distance connections were few in comparison with the island’s regional trading network. The orientation of Curaçao’s port towards different parts of the Americas changed through time, with increasing engagement with the North and South American mainland and decreasing engagement with the Greater and Lesser Antilles. However, South America and the Lesser Antilles remained the most important trading regions through time.

This was a continuation, or even an intensification, of a pattern already observed in the eighteenth century. Linda Rupert notes in her book Creolization and Contraband that at the peak of Curaçao’s direct transatlantic trade in 1783, 80 vessels made this journey in one year. This was a marked increase from numbers in the first half of the eighteenth century when an average of 14 or 15 vessels sailed from Curaçao to the Netherlands per year.[7] However, it is still more than twice the number of such vessels observed in the early nineteenth century. Peak years of the eighteenth century saw over 1,000 total incoming vessels, but in 1816-1817 and 1825-1826, the yearly averages are much lower, at 559 and 408 respectively.[8] We can therefore observe that the number of vessels recorded trading through Curaçao’s entrepôt had decreased by half since the 1780s.

Conclusion

Although it is important to remember that Curaçao had also been long embedded in clandestine trading networks that would not necessarily have been recorded in the newspaper, the data presented above show that during the first decades of the nineteenth century Curaçao was closely connected to other Antillean islands (particularly those of the Lesser Antilles), and the Spanish mainland.[9] It was part of a trans-imperial trading network through which Curaçaoan islanders were connected to communities and markets well beyond the shores of their island. Besides having their commercial function, the vessels also facilitated a network of communication. Incoming vessels often brought the latest foreign newspapers to Lee.[10] While Curaçao’s transatlantic trade was insignificant, its position in a trading network that linked the Antillean islands together enabled him to provide his readers with an outlook on the world.

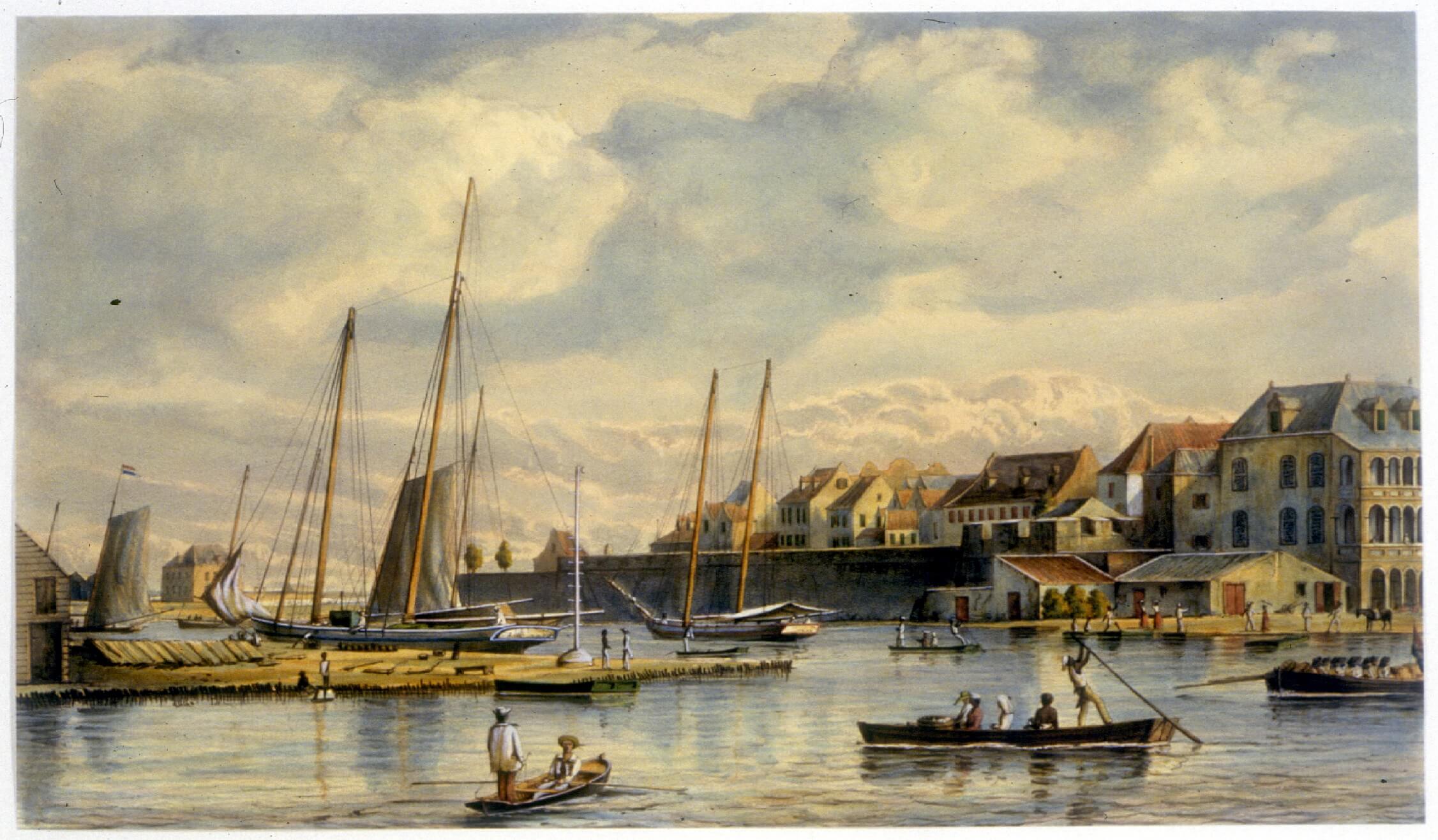

Figure 8: "Boating Activities, Curaçao, Dutch West Indies, ca. 1860", Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed June 2, 2022, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/897

[1] Maritza Coomans-Eustatia, “Notes on Early Printing in the Dutch Caribbean Islands,” in History of Literature in the Caribbean, Volume 2: English- and Dutch-Speaking Regions, ed. A. J. Arnold (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2001), 370–71.

[2] Roderick Cave, “Early Printing and the Book Trade in the West Indies,” Library Quarterly 48, no. 2 (1978): 179.

[3] Lee was not alone. In the early 1790s, Jamaican newspapers also recorded the daily arrivals of foreign vessels: Julius S. Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution. (Brooklyn: Verso, 2018), 46.

[4] De Curaçaosche Courant is digitized at Delpher: https://www.delpher.nl/

[5] Linda Rupert, Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2012), 136.

[6] Wim Klooster, “Curaçao and the Caribbean Transit Trade,” in Riches from Atlantic Commerce: Dutch Transatlantic Trade and Shipping, 1585-1817; Rupert, Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World, 104, 119.

[7] Rupert, Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World, 120-121.

[8] Rupert, Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World, 121.

[9] Rupert, Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World, 121.

[10] De Curaçaosche Courant, 23 August 1817.