Incoming Vessels in De Curaçaosche Courant: A Quantitative Microhistory, 1833-1834 and 1845-1846

By Felicia Fricke and Hannah Hjorth

De Curaçaosche Courant (whose earlier history is described in the IN THE SAME SEA blog post dated 15 June 2022) continued providing its readers with shipping information in the 1830s and 1840s. The original printer, William Lee, had died in 1823 and been succeeded by his wife, Margaritha Engelbron, who ran the business until her death ten years later[i]. The printshop in Willemstad was then taken over by Muller and Neuman, who had probably been apprentices before Margaritha’s death[ii]. Names of vessels masters in the shipping lists indicate that both men may have had relatives in the business of shipping, forming an extra link to the network of sailors who stopped at Willemstad, providing them access to news, rumour, gossip, and foreign newspapers[iii].

Figure 1: Boats in Harbor, Curaçao, Dutch West Indies, ca. 1860 - slaveryimages.org.

However, there was a change in the style of the shipping lists newspaper during this period. In the 1830s, De Curaçaosche Courant no longer listed the destinations of vessels leaving Willemstad. This could have been for many reasons, but perhaps the most pertinent is that vessels plying contraband trade might not wish to have their destinations advertised. This means that graphs cannot be developed for outgoing vessels in 1833-1834 and 1845-1846. Between 1837 and 1844 there were no shipping lists at all. This gap determined the years selected for analysis in this post.

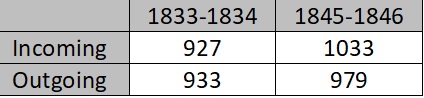

The data presented below represent a total of 1960 incoming and 1912 outgoing vessel itineraries to Curaçao across four years (see Table 1). This was an average of approximately 39 incoming and 39 outgoing vessels per month in 1833-1834 and 43 incoming and 41 outgoing vessels per month in 1845-1846. These numbers do not demonstrate much of a change in overall shipping traffic over a period of fourteen years.

Table 1: Incoming and outgoing vessel numbers for 1833-1834 and 1845-1846.

Table 1: Incoming and outgoing vessel numbers for 1833-1834 and 1845-1846.

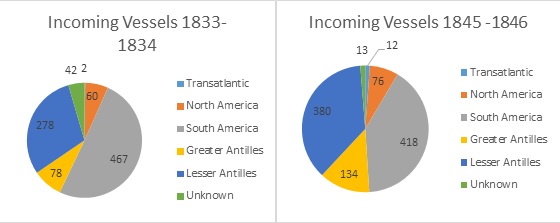

Figure 2 (below) shows vessels entering Willemstad during the two selected periods. South America was the most common vessel origin in both periods, followed by the Lesser Antilles, although contact with both the Lesser and Greater Antilles increased in the later period, while links with South America declined slightly. Transatlantic connections make up only a fraction of this trade, although there is a certain amount of error inherent in the ‘unknown’ category, which could contribute to any or all of the others. The slight decline in traffic to South America may reflect the post-independence period and the economic situation of states attempting find their feet after severing connections to Spain and Portugal.

Figure 2: Origins of vessels coming into Willemstad (Curaçao) in 1833-1834 and 1845-1846.

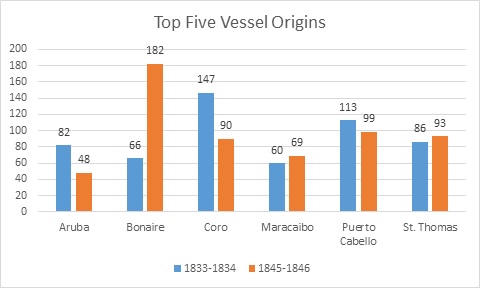

The top five most common vessel origins are shown in Figure 2. The largest changes over time are seen in connections with Bonaire (a massive increase), Aruba, and Coro (both decrease). In contrast, connections with Maracaibo, Puerto Cabello, and St. Thomas remained quite stable.

Figure 3: Comparison of top five vessel origins in 1833-1834 and 1845-1846.

Shifting Vessel Origins, 1816-1846

When compared with the data for vessel origins in 1816-1818 and 1825-1826, in the 1830s and 1840s we see a slight recovery from the lower number of vessels recorded for the 1820s, although not increasing to the levels of the 1810s. Incoming vessels from South America make up approximately half of the shipping across all periods, while the proportion of vessels from the Lesser Antilles falls in the 1820s and recovers in the 1830s and 1840s, reaching a high in the 1845-1846 period. In the 1840s, the top five vessel origins see the important introduction of Bonaire, while Coro declines from its height in the 1820s and 1830s. Aruba as a vessel origin declines consistently across all periods. Puerto Cabello and St. Thomas are in the top five vessel origins across all periods, while Puerto Rico drops out of the top five altogether in the 1830s and 1840s. The almost complete absence of transatlantic vessels entering Curaçao in the 1830s and 1840s also follows the declining trend seen through the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries[iv].

There may be a number of reasons for these trends. An overall drop in shipping (and in shipping from the Lesser Antilles) during the 1820s may be related to the highly uncertain Caribbean environment during this period, as the region was unsettled by hurricanes, fluctuating sugar markets, war, and social change[v]. Curaçao was additionally troubled by water shortages and an epidemic[vi]. In 1827, Willemstad was declared a free port in order to attract trade[vii]. This may account for the increased shipping in the 1830s and 1840s. The economy would subsequently continue to improve in the second half of the nineteenth century[viii].

Meanwhile, the introduction of Bonaire as an important vessel origin in the 1840s may be related to salt production or contraband trade with South America[ix]. At this time, most of the enslaved people on Bonaire were owned by the Dutch government and worked in the salt pans to supply international shipping with a food preservative[x]. There were also warehouses used by Spanish American smugglers[xi].

Overall, the shipping lists in De Curaçaosche Courant between 1816 and 1846 illustrate a Curaçaoan trade environment that was much more closely connected to micro-regional destinations (especially the coast of South America and the Lesser Antilles) than to destinations in North America or on the other side of the Atlantic. This is important for our understanding of Willemstad as a port city, but also for our understanding of news, transport, and trade networks in the Caribbean during the first half of the nineteenth century.

[i] De Curaçaosche Courant, 1823-08-16, 1833-08-03 (Delpher.nl)

[ii] De Curaçaosche Courant, 1833-08-31 (Delpher.nl)

[iii] De Curaçaosche Courant, 1824-06-12, 1849-05-26 (Delpher.nl)

[iv] Felicia Fricke et al., ‘Vessel Itineraries in De Curaçaosche Courant: A Quantitative Microhistory, 1816-1818 and 1825-1826’, 15 June 2022, https://inthesamesea.ku.dk/blog/vessel-itineraries-in-de-curacaosche-courant-1816-1818-and-1825-1826/#_edn7

[v] Patrick Baker, Centring the Periphery: Chaos, Order, and the Ethnohistory of Dominica (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994), 98–99; Laurent Dubois, ‘The nineteenth century: consolidation and reconfiguration’, in J. Miller (ed.) The Princeton Companion to Atlantic History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 46-54; Sami Bensassi, Preeya Mohan, and Eric Strobl, ‘A storm in a teacup? Hurricanes and sugar prices in the first half of the nineteenth century’, Weather, Climate and Society 9(4):753-768, 2017; Hollis Micheal Tarver, The History of Venezuela (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC., 2018), 53–64; Karly Kehoe, ‘Colonial collaborators: Britain and the Catholic Church in Trinidad, c. 1820-1840’, Slavery & Abolition 40(1):130-146, 2019; Edward Cox, Free Coloreds in the Slave Societies of St. Kitts and Grenada, 1763-1833 (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1984), 7–9.

[vi] Jack Schellekens, De rijke geschiedenis van Curaçao: Indianen, de WIC en invasies (Amsterdam: Caribpublishing, 2012), 88.

[vii] Schellekens, De rijke geschiedenis van Curaçao, 89.

[viii] Schellekens, De rijke geschiedenis van Curaçao, 89.

[ix] Linda Rupert, Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2012), 124, 142.

[x] Kwame Nimako and Glenn Willemsen, The Dutch Atlantic: Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation (London: Pluto Press, 2011), 65.

[xi] Rupert, Creolization and Contraband, 124; Ruud Stelten and Konrad Antczak, ‘Life at the salty edge of empire: the maritime cultural landscape at the Orange Saltpan on Bonaire, 1821-1960’, International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 2022, DOI: 10.1007/s10761-022-00660-9; Konrad Antczak, ‘Bonaire and Curaçao’, The SHA Newsletter 54(2):21-25, 2021.