WORKING PAPER 3: Missionary Networks, Black Preachers, and the Spread of Methodism in the Antilles

By Marie Keulen, 19 January 2022

In this working paper, Marie Keulen writes about the initiation of the Methodist missions in the Antilles. By travelling, preaching, and communicating between British, Dutch, and Danish islands, Methodist missionaries transcended imperial boundaries and created missionary networks. Keulen specifically focuses on the Dutch island of St. Eustatius, where free and enslaved men and women of colour were not only the recipients of the gospel but also the main preachers and religious leaders on the island.

In the late eighteenth century, numerous Protestant missionaries, who came to be known as Methodists, visited various islands in the Antilles, where they would establish religious communities among the white, enslaved, and Indigenous populations inhabiting these islands. One of the leading figures in this period was Thomas Coke, who played an important role in the founding and spread of Methodism in North America, the Caribbean, and many other places around the world. Between 1786 and 1793, he would make four visits to the Antilles, visiting twelve different British, Dutch, and Danish islands. Coke wrote about his journeys through the Caribbean in his journals, composed of letters that he originally exchanged with the founder and leader of the Methodist movement, John Wesley, and which were published in the 1780s and 1790s. By the time of Coke’s last visit to the Caribbean, the number of Methodist missionaries active in the region had increased from one to twelve, and missionaries would often travel between the different Methodist communities on the different islands. Thus, instead of being isolated events, the Methodist missions on the Antillean islands were part of a broader missionary endeavour transcending imperial boundaries. Coke and his fellow missionaries came with the same religious agenda to different islands within different empires, where they would encounter different situations, responses, and challenges.

Too often, the history of Christian missions in Caribbean colonial societies has been studied in isolation, being fragmented and divided along lines of denomination, empire, and even individual colony. By examining a missionary who was moving, preaching, and communicating between islands, we can begin to understand the role of missionaries and the meaning of missionary encounters in the Caribbean as a whole. Whereas most historians have concentrated on the local scale of individual colonies when investigating Christian missions, foregrounding the regional scale of the Methodist missions gives a different perspective on the encounters that took place between missionaries and the different groups inhabiting the Antillean islands. It exposes the importance of missionary networks and sheds light on the way missionaries profited from and created them. For Coke and the missionaries accompanying him on his journeys, the Antilles seemed to be a space where they could move freely and spread their religion. However, on the Dutch island of St. Eustatius, these white European missionaries were confronted with the unwelcoming attitudes of the local colonial authorities. On St. Eustatius, the white Methodist efforts led by Coke intersected with the Afro-Methodist community already present on the island. In this paper, I connect the early history of Methodism on St. Eustatius, in which free and enslaved people of colour played a pivotal role, to the broader story of the spread of Methodism and Methodist missionaries in the region.

We know that throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, the reactions from planters, slave owners, and colonial administrations to Protestant missionary groups hoping to convert their enslaved populations could be both positive and negative. As missionaries arrived in colonial slave societies, a new social and cultural group influenced the relationship between slaves, masters, and the authorities. Further research is needed to fully understand the role of missionary encounters in Caribbean slave societies and to get a better understanding of how missionaries maintained, undermined, or changed the institution of slavery and the practices upon which slavery was founded. Various historians have emphasized that anti-missionary and anti-conversion attitudes were widespread among colonists in the British, Danish, and Dutch Atlantics. This interpretation suggests that Christian missions undermined the institution of slavery. At least, it points out that the people invested in the institution of slavery – the planters, slave owners, and colonial administrators – were convinced of the pernicious effects of slave conversion. Yet, there were always planters and slave owners who had a positive attitude towards missionaries, who were in favour of slave conversion, or who were even actively involved in attracting missionaries to their estates. In general, missionary groups received both welcoming and hostile reactions to their presence, as was also the case with the Caribbean Methodist missions, and these reactions were often connected to particular island conditions. In the case of St. Eustatius, the existence of a strong Afro-Methodist community may explain why missionary efforts were met with scepticism and hostility.

Frontpage of the journals of Thomas Coke. Extracts of the Journals of the Rev. Dr Coke’s Five Visits to America (G. Paramore, 1793).

The Foundation of the Methodist Caribbean Missions

Although there had been a Methodist community in Antigua since the mid-eighteenth century, initiated by a Methodist-inspired planter, it was not until the arrival of Coke in the Antilles that one could speak of an organized trans-Atlantic effort to spread Methodist Christianity in the Caribbean. It was only by coincidence that Coke, on his second journey to North America, accompanied by three fellow preachers, entered Caribbean waters for the first time and set foot on the island of Antigua in 1786. During his voyage, the ship he had boarded from England got into trouble when sailing into a hurricane, which forced the captain to head for the West Indies instead of North America. Once there, Coke was struck by “the wonderful openings we have in these parts” and continued his journey visiting Dominica, St. Vincent, St. Christopher, Nevis, and St. Eustatius before heading for his original planned destination.[i] With these words, Coke engages in a long-standing colonial discourse that views the Caribbean as a beautiful place that has a lot to offer Europeans – in this case, many new converts. Within the seven years that followed, Coke would make three more visits to the Antillean region, each time reaching out to more and more islands and including them in the Methodist missionary network. The preachers who followed him on his journeys stayed behind on the various British, Dutch, and Danish islands, gathering followers, organizing congregations, and building networks with the wider Methodist community, the planters, officials, merchants, soldiers, sailors, and slaves inhabiting the islands, and possibly other religious groups.

The Methodist missionaries aimed to spread the gospel among all the different groups inhabiting the Antillean islands, preach to as many people as possible, and establish flourishing congregations with large numbers of members. The audience they hoped to reach included white elites, such as planters, government officials, and merchants, non-elite white people, such as sailors and soldiers, and non-white people, such as enslaved men and women, free people of colour, and Indigenous people. Although Methodists preached to both Black and white people – both slaves and their masters – the two groups were separated in congregational structures and practices. Based on what we know from the other Caribbean and North American missions, it seems likely that this also affected the content of the preaching and that the missionaries emphasized different messages in their sermons depending on their audience.[ii] In his journal, Coke frequently mentions his contacts and interactions with planters and merchants who were interested in his religious ideas, invited him over for dinner, encouraged the missionaries in their efforts, and offered them their help and support. It was, however, the enslaved population that was the most significant and largest group of (potential) converts for the Methodist missions in the Caribbean.

The significance of Africans and their descendants for the growth of the Methodist congregations becomes clear when looking at the membership numbers in the early 1790s, in which “whites”, “coloured people”, and “blacks” are registered separately, with the first group being only tens and the latter two groups, sometimes categorized together, being hundreds or even thousands of people per colony.[iii] This situation in the Antilles differed from that of the North American context with which Coke had been familiar before travelling through the Caribbean. In North America, white people made up a far larger proportion of both society in general and the Methodist community in particular. Despite the significant presence of Black people in the Methodists’ Caribbean congregations, these men and women do not play an important role in Coke’s journal. In most cases, the many enslaved people whom the Methodists see as potential converts, are briefly mentioned as a group, for example as an audience to a sermon. Rarely do we get to know the individual people forming these groups and their reactions, actions, opinions, and feelings towards the missionaries?

View of the Methodist chapel in Charlestown on the island of Nevis. The engraving shows different social groups. In the front, there is a group of five well-off women accompanied by three Black (possible enslaved) women sitting on stones. The back of the picture includes two separate groups of three white men and three women conversing. Printed in: Thomas Coke, A History of the West Indies, 3 vols (London: 1811), III. Held by the John Carter Brown Library.

Missionary Networks

Reading through Coke’s journals, it is striking how, in this early phase of the Methodist missions in the Caribbean, Coke and his fellow companions became part of an extensive network across the British, Dutch, and Danish islands of the Antilles. Whenever Coke and the two or three missionaries travelling with him arrived in a new colony, they would soon be supported by planters and merchants in favour of their missionary endeavours. Sometimes they already knew people living on the respective island, due to personal connections or because people had moved from another Caribbean island where they had already met with the Methodist religion. For example, when Coke went to Dominica a couple of days after his first arrival at Antigua, he was invited to the house of Mrs Webley, “a Mulatto Gentlewomen of some property”, who was an acquaintance of “brother” John Baxter, a missionary who had been preaching on Antigua on his own accord and who was now accompanying Coke on his journey through the Antilles. Webley encouraged Coke to give a sermon in her house, an invitation of the kind that the missionary frequently got from the various white people he met during his journeys.[iv]

Most of the time, however, the missionaries would come into contact with people they did not know. Yet, even in these cases, Coke and his companions would oftentimes not arrive empty-handed. Using Coke’s wider network from London and Baxter’s network from Antigua, they armed themselves with recommendation letters, sometimes written for specific planters whom they had heard would be positive concerning their mission ambitions. In some cases, “warm letters of recommendation” were not even necessary, for example when the missionaries met a planter on Dominica who had been a member of the Methodist society in Dublin, or when they encountered a merchant in Barbados who had heard Coke preach in Baltimore and Maryland.[v] Coke and Benjamin Pearce, the missionary accompanying him at that moment, came into contact with this Barbadian merchant because a group of soldiers had told them that the said merchant had provided the soldiers with a room for prayer. He also proved to be a helping hand for the missionaries: “His house, his heart, his all seemed to be at our service,” wrote Coke.[vi] This was not the only time the travelling Methodist missionaries were tipped off by islanders mentioning planters, merchants or other people who they thought would be willing to help the missionaries’ cause. Many times, white elites would pro-actively use their networks for the benefit of the newly arrived missionaries. It is surprising how fast the news of the arrival of the Methodists spread in the harbours they arrived at and the islands they visited. Sometimes the news was even faster than the missionaries themselves. For example, when Coke travelled to St. Eustatius, several free Black people of the existing Methodist community had already received word from St. Christopher that he intended to visit the island.[vii]

Not only did Coke and his companions profit from existing networks, but they also created new networks as they travelled from one island to the other. Indeed, their way of organizing the Methodist missions in the Antilles – with the custom of ‘travelling’ missionaries who regularly changed residence – contributed to the creation and maintenance of inter-island and inter-imperial networks. Visiting the different British, Dutch, and Danish Antillean islands several times in the years between 1786 and 1793, Coke made sure to stay in contact with various white elites after meeting them for the first time. He was well aware of the importance of these connections and actively used them for the Methodist cause by making sure that the missionaries who stayed behind on the islands were well provided and connected. His journals are full of descriptions of the constant encounters with interested, encouraging, and helpful people who aided the missionaries in finding preaching houses, accommodation, and audiences. Coke also made sure to include the local colonial authorities of the various Antillean islands in his network, whose support he actively sought. Oftentimes, missionary-positive slave owners invited the Methodists to preach to their slaves, ‘offering’ them as potential converts. The voices of the concerned enslaved men, women, and children themselves are remarkably absent in Coke’s journals, which suggests that the Methodist missionaries reached the enslaved population not directly but indirectly through their masters.

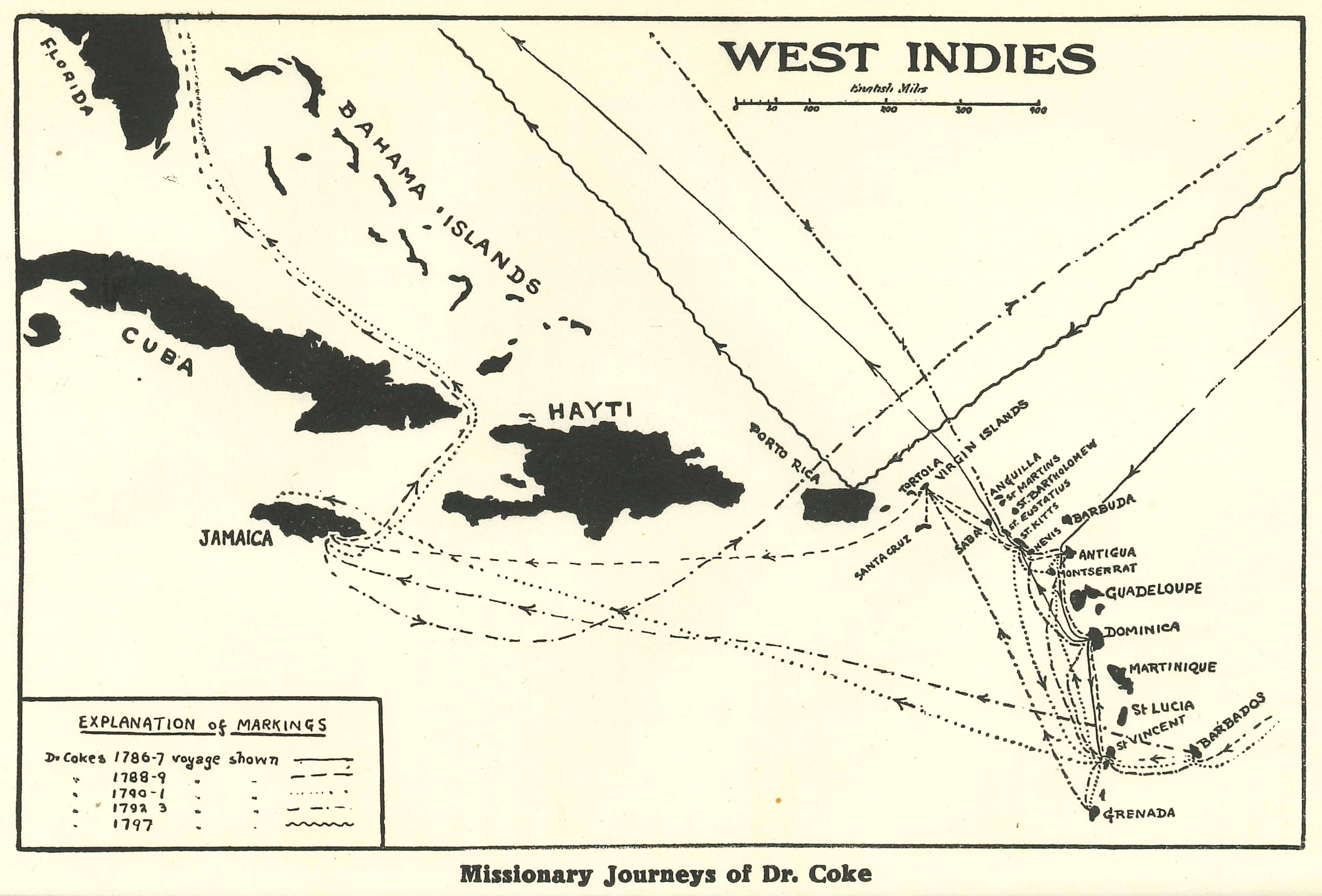

Map of the Antilles showing the four voyages of Thomas Coke through the Caribbean. In 1797, Coke made a fifth brief visit to the Antilles, when he stayed in Puerto Rico before travelling to North America. Source: Findlay, G. G., and W. W. Holdsworth, The History of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society, 5 vols (London: The Epworth Press, 1921), II, p. 27.

Map of the Antilles showing the four voyages of Thomas Coke through the Caribbean. In 1797, Coke made a fifth brief visit to the Antilles, when he stayed in Puerto Rico before travelling to North America. Source: Findlay, G. G., and W. W. Holdsworth, The History of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society, 5 vols (London: The Epworth Press, 1921), II, p. 27.

Anti-Missionary Opposition on the Dutch island St. Eustatius

The image that arises from Coke’s journals of the early Methodist missions in the Antilles is very optimistic in terms of institutional support. On almost all the islands where Coke and his companions set foot, they received a warm welcome from planters and authorities alike and they were explicitly allowed to proselytize to the enslaved population. Within this context, the distrustful and, according to Coke, blatantly hostile attitude of the local administration on the Dutch island of St. Eustatius is striking. In his journals, Coke pays a lot of attention to the anti-missionary attitude of the Governor of St. Eustatius, Johannes Runnels (in Coke’s journal referred to as ‘Rennolds’), which eventually led to the persecution of Methodists preachers on the island. On the one hand, Coke is optimistic when he describes the work being done by Methodist preachers and the followers they have among the enslaved population. On the other hand, he is pessimistic when it comes to the attitude of the local administration, in particular the Governor, comparing this hostile attitude to the more welcoming and friendly reception on neighbouring islands.

When in 1787, Coke, together with three fellow missionaries, arrived on St. Eustatius for the first time, he encountered an island on which a vibrant and strong Afro-Methodist community was in open conflict with colonial authorities. The community was led by a Black man named Harry, also known as ‘Black Harry’, who came as a slave from North America, where he had been a member of the Methodist Society.[viii] On other islands in the Antilles, Coke appears to have succeeded with a missionary intervention primarily borne by white preachers. The situation in St. Eustatius, however, was different. Due to the strong Methodist community already in place, and the discomfort and uneasiness this aroused among the elites, Coke and his missionary efforts were confronted with anti-missionary sentiments from colonial authorities. Immediately upon their arrival on the island, the group of white Methodist missionaries learned about the unfavourable and unenthusiastic attitude of the authorities concerning the existing Methodist community; the Governor had just forbidden Harry “to preach any more” under penalty of severe punishments.[ix] Coke and his companions also had to answer government officials. Until the colonial authorities “had considered whether our religion should be tolerated or not”, the white Methodists were not allowed to appear in public.[x]

Late eighteenth-century engraving of St. Eustatius, portraying the harbour Orange Bay and the various vessels visiting the island. The Dutch Reformed Church (number 3, centre left) is one of the most prominent buildings in the depicted landscape. Gezigt van het Eyland St. Eustatius, [approximately 1780], etching/copper engraving, 26 x 41,5 cm, Leiden University Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:53042.

Late eighteenth-century engraving of St. Eustatius, portraying the harbour Orange Bay and the various vessels visiting the island. The Dutch Reformed Church (number 3, centre left) is one of the most prominent buildings in the depicted landscape. Gezigt van het Eyland St. Eustatius, [approximately 1780], etching/copper engraving, 26 x 41,5 cm, Leiden University Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:53042.

When, two years later, in 1789, Coke again visited St. Eustatius during his second journey through the Antilles, the position of Governor Runnels towards the Methodist preachers on his island had not changed. Immediately upon their arrival, Coke and the missionaries accompanying him found out that Harry had been “publicly whipped, imprisoned and banished” from the island. Moreover, the administration of St. Eustatius had promulgated an ordinance in which preaching and praying by white people and people of colour was prohibited. Coke interprets the ordinance, which he partly quotes in his journal, as “persecution against religion itself” – against all forms of Christian prayer.[xi] It seems more likely, however, that the ordinance targeted specific religious groups such as the Methodists, leaving the accepted Dutch Reformed Church, Anglican Church, and Lutheran Church unaffected.[xii] Despite this explicit prohibition, Coke decided to stay on the island for a month to devote himself to preaching to the island’s congregation. This, however, did not go unnoticed, and soon Coke and his companions were summoned before the government with the demand that they would not “publicly or privately, by day or by night, preach either to whites or black” during their stay on the island.[xiii] In the years that followed, similar confrontations would take place during Coke’s third and fourth visits to St. Eustatius.

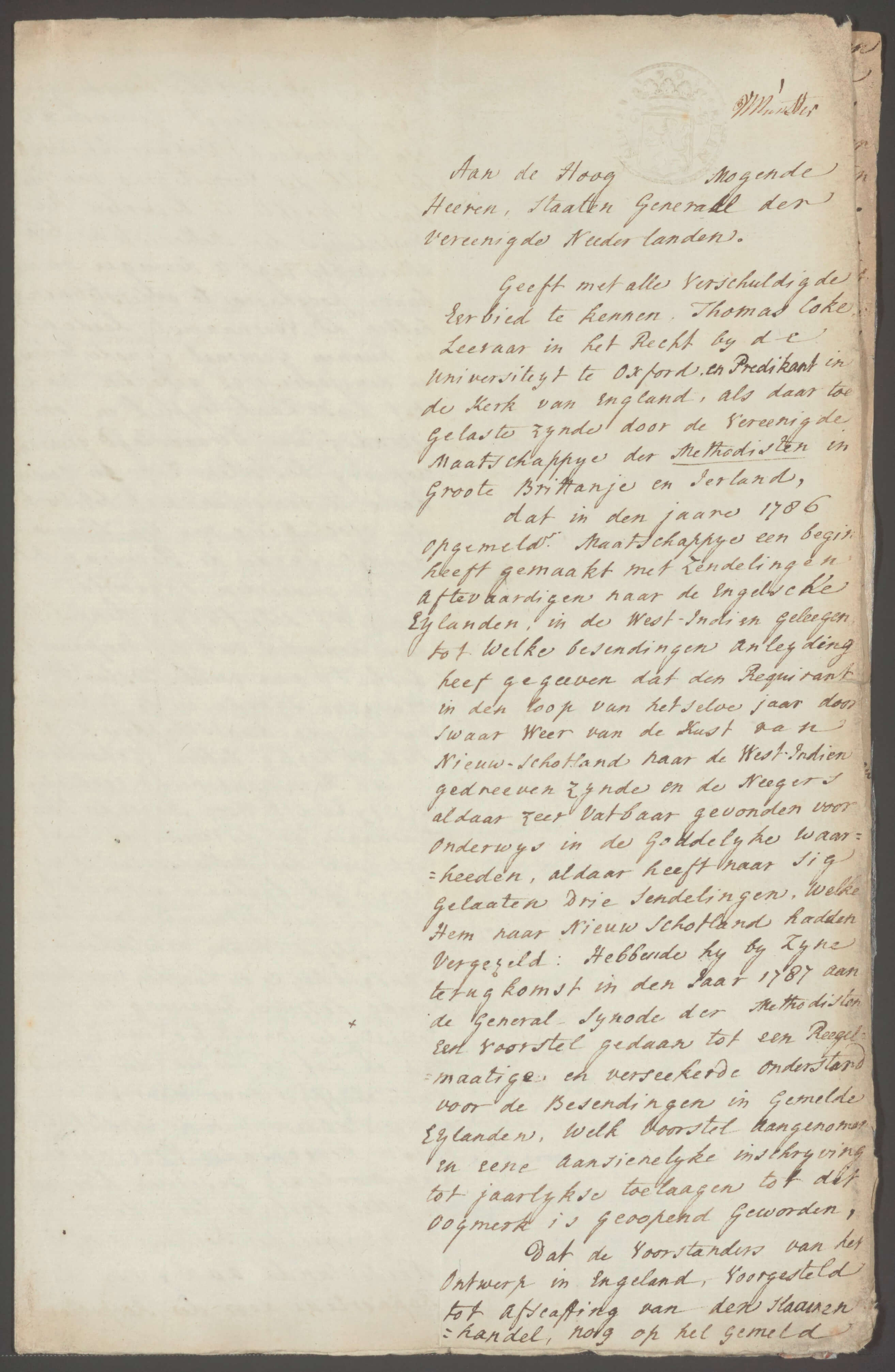

These difficulties experienced by Coke and other British Methodist missionaries visiting the Dutch island, as well as the persecution and banishment of Black preachers and enslaved followers, did not stop Coke’s determination to spread the Methodist religion on St. Eustatius. In 1794, two years after his last visit to the island, Coke travelled to the Dutch Republic to request the States-General’s permission for the Methodist missions in the Dutch West Indian islands. He accompanied his request with letters of recommendation from the British politician Henry Dundas and the Methodist Society in Great Britain and Ireland, emphasizing that the Methodist missionaries were “virtuous, pious and useful men” who were loyal and obedient to the law and who laboured “to make the Negroes faithful and obedient servants to their masters”.[xiv] In his request, Coke also tried to underline the favourable effects of slave conversion for slave owners, arguing that Christian slaves would be more obedient, work harder, and therefore be more valuable than non-Christian slaves. With these statements, and by explicitly distancing the Methodist Society from the abolitionist movements in the British Empire, Coke made sure that in his communication to the States-General the underlying conditions of the institution of slavery were acknowledged, and even reinforced.

Coke’s appeal to the highest political body of the Dutch Republic had no consequences for the situation of the Methodists on St. Eustatius, however. In 1804, the local administration issued another ordinance prohibiting anybody except those with special permission to preach or to be involved in any religious teachings whatsoever. The reason mentioned for this ordinance, which was repeated four years later, was

[…] that here, by day as well as by night, various assemblies and meetings of both free people of colour and slaves are held, in which both free people of colour and slaves preach or are in other ways involved in religious practices […].[xv]

This statement shows that not only did the Government of St. Eustatius persist in their attempts to ban Methodism from the island, but the same was true for the free and enslaved men and women of colour involved in preaching and communal prayer.

The first page of Thomas Coke’s request to the States-General of the Dutch Republic from 1794. NL-HaNA, 1.05.01.02, inv. no. 1333.

The first page of Thomas Coke’s request to the States-General of the Dutch Republic from 1794. NL-HaNA, 1.05.01.02, inv. no. 1333.

The Black Methodist Community of St. Eustatius

Before, during, and after Coke’s visits, Black men and women formed the Methodist Society of St. Eustatius. It was the existence of this community of believers rather than abstract contradictions between slavery and the Christian mission, which explains the suspicious and hostile attitude of the authorities of St. Eustatius towards Methodism in general. Black men and women were not only the recipients of the gospel but also the main preachers and religious leaders on the island. Not the white European missionary Coke but the Black formerly enslaved man Harry was the one who first introduced Methodism to the island and its inhabitants. With his preaching, Harry is said to have greatly touched his audience, with whom he shared a common experience of the hardships of living in slavery. The enslaved men and women listening to, praying with, and singing along with Harry “were so affected under the word, that many of them fell as if they were dead, and some of them would remain in a state of stupor for some hours” – which was a thorn in the side of the slave owners and colonial authorities.[xvi] It is no coincidence that Coke and his fellow British companions received fierce anti-missionary opposition on the Antillean island where Methodism was first introduced by a Black spiritual leader surrounded by a free and enslaved community of colour.

Harry was not the only Black preacher and leader of the Afro-Methodist community on St. Eustatius. The hostile attitude towards Methodism made it impossible for Coke to station one of his fellow white missionaries on the island – a common practice that had enabled Coke to set up a network throughout the Antilles and to keep close control over the Methodist religious communities on the different islands. The absence of a stationed British missionary in these early years at the end of the eighteenth century left more room for the religious and organizational leadership of the free and enslaved Black people involved in the Methodist community of St. Eustatius. Besides the attention to the story of Harry – whose persecution by the colonial authorities is described by Coke as an act of heroic martyrdom – Coke’s journals frequently mention the prominent role of free Black people within the religious community. Many of these people, whom Coke rarely mentions by name, were “awakened by Harry” and given the latter’s prominent role in the early Black Methodist community, it seems likely that it was through Harry that Methodism first arrived on St. Eustatius. Besides Harry, there was also another person with North-American ties, a Black woman, only briefly mentioned by Coke, and whose name we, unfortunately, do not know.

Despite the difficulties experienced by both the British missionaries visiting St. Eustatius and the Methodist followers and preachers on the island, throughout the 1780s and 1790s the number of followers of the Methodist congregation grew. This happened in a period when the population of St. Eustatius, especially the enslaved population, increased enormously from more than 3000 people in 1779 to almost 8000 people in 1790.[xvii] After baptizing almost a hundred and forty people during his second visit to the island, Coke notices that “even under this heavy cross and hot persecution, our numbers amount to two hundred and fifty-eight; and of those, we have reason to believe, that one hundred and thirty-nine have tasted that the Lord is gracious”.[xviii] Methodist religion proved to be attractive for a small but significant part of the enslaved and free Black population. Although there were various other religious groups on the Dutch island, such as the Dutch Reformed, Jews, Anglicans, and Lutherans, none of these groups directed their efforts toward converting the Black men and women inhabiting the island. Methodist preaching and communal praying attracted a substantial group of followers and people who occasionally joined these religious meetings out of curiosity.

Even though during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries no British missionaries were stationed on the island, the Methodist congregation on St. Eustatius, in which Black preachers and leadership were fundamental, was embedded in the broader Methodist Antillean network. Although Governor Runnels made it very clear that he was not welcome on the island, Coke did visit St. Eustatius every time he was in the Caribbean. Seven other missionaries had joined him on these different trips and every time Coke and his companions set foot on St. Eustatius, they were very involved in the Methodist community on the island. Coke also tried to strengthen the communal structure of the congregation by implementing classes, small groups of members of the Methodist congregation who collectively prayed, read the scriptures, shared their spiritual experiences, and listened to exhortations under the guidance of a leader. Before leaving St. Eustatius after his first visit, Coke formed six classes, three “to the care of Harry”, “two to our North American sister, and one to a black named Samuel”.[xix] During one of his later visits, one of the leading figures in the community expressed his wish to be in more direct contact with Coke and with the Methodist community on St. Christopher. A “considerable number of brethren and sisters that were free negroes” were planning to head to this neighbouring British island, to strengthen inter-island Methodist ties and to enjoy religious ceremonies together.[xx]

During the nineteenth century, persecution and mistrust gradually made a place for acceptance, and in 1811 the Methodists gained freedom of religious practice.[xxi] On other Antillean islands, there was an opposite development where persecution and anti-missionary sentiments replaced initial acceptance. Due to these local differences in the circumstances, responses, and challenges that the Methodists encountered, their missions throughout the Antilles cannot be reduced to the situation on an individual island. From their inception in the late eighteenth century to their spread and growth in the nineteenth century, the Caribbean Methodist missions have always been part of a broader missionary endeavour transcending imperial boundaries. Within this context, people such as Coke, his companions, Black Harry, and the free and enslaved Black people of St. Eustatius profited from and created inter-island and trans-Atlantic missionary networks.

[i] Thomas Coke, An Extract of the Rev. Dr. Coke’s Journal, from Gravesend to Antigua, in a Letter to the Rev. J. Wesley (J. Paramore, 1787), p. 12.

[ii] For example Gerbner describes how Moravian missionaries adapted their religious message in the Danish West Indies to the wishes and concerns of both planters and Afro-Caribbean enslaved people: Gerbner, pp. 167–171.

[iii] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, pp. 187–188.

[iv] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 78.

[v] See respectively: Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, pp. 80; 94.

[vi] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 94.

[vii] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 82.

[viii] Not to be confused with Harry Hosier, an African-American Methodist preacher during the Second Great Awakening who was during his life also known as ‘Black Harry’.

[ix] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 83.

[x] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 83.

[xi] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 110.

[xii] The Dutch Reformed Church was the official church of the island. The other accepted religious groups during this period were the Jews, the Anglicans, the Lutherans, and even the Roman Catholics. Yet, in the eighteenth century, the Roman Catholics had no public church on the island. For more about religious places in the landscape of St. Eustatius see Derek R. Miller and R. Grant Gilmore, ‘Negotiating Tensions: The Religious Landscape of St. Eustatius, 1636–1795’, Journal of Social Archaeology, 16.1 (2016), 56–78.

[xiii] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 111.

[xiv] National Archives, The Hague (NL-HaNA), 1.05.01.02, Inventaris van het archief van de Tweede West-Indische Compagnie, inv. no. 1333, Rekest van Thomas Coke, methodist, aan de Staten-Generaal, met afschriften van geleidebrieven van de Engelse ambassadeur Dundas en raadspensionaris Van der Spiegel, en een getuigschrift van methodisten uit Amsterdam.

[xv] NL-HaNA, 1.05.13.01, Inventaris van de archieven van St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba, inv. no. 72, Notulen van de vergaderingen van de gouverneur (commandant) en de Raad van Politie, 14 April 1804, image 110-111; NL-HaNA, 1.05.13.01, inv. no. 82, Register van publicaties, proclamaties en notificaties, 12 April 1804, image 11; NL-HaNA, 1.05.13.01, inv. no. 82, 15 December 1808, image 73.

[xvi] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 83. This image of the powerful effect of Black Harry's preaching upon his audience has also survived in oral history: Felicia Jantina Fricke, ‘The Lifeways of Enslaved People in Curaçao, St Eustatius, and St Maarten/St Martin: A Thematic Analysis of Archaeological, Osteological, and Oral Historical Data’ (University of Kent, 2019).

[xvii] Norman F. Barka, ‘Citizens of St. Eustatius, 1781: A Historical and Archaeological Study’, in The Lesser Antilles in the Age of Expansion, by Robert L. Paquette and Stanley L. Engerman eds. (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996), pp. 223–38 (p. 234).

[xviii] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 110.

[xix] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 84.

[xx] Coke, The Journals of Dr. Thomas Coke, p. 138.

[xxi] NL-HaNA, 1.05.13.01, inv. no. 72, images 467–469.