WORKING PAPER 7: Widows’ Interisland Inheritances in St. Eustatius and St. Barths, 1796-1819

By Felicia Fricke.

With the death rate for European men extremely high, married women in the Caribbean in the late 1700s or early 1800s could reasonably expect one day to become a widow, a prospect that presented them with a number of challenges, responsibilities, and opportunities.[1] Here, I will discuss how women navigated the landscape of widowhood across late eighteenth and early nineteenth century St. Eustatius and St. Barths. In this period, Dutch St. Eustatius was at the beginning of an economic decline instigated by the invasion of the British under Admiral Rodney in 1781. At the same time, Swedish St. Barths was a prosperous free port island with many Statian residents.[2] In the multilingual, multi-imperial eastern Caribbean, the short distances between islands and the high employee turnover in many professions facilitated interisland movement, connections, and estates.[3] St. Eustatius’ multinational context is shown, for example, by newspapers dating to the 1790s, which include texts in English, Dutch, and French.[4] How did these circumstances manifest as a benefit or a drawback to Statia’s widows?

In addition to the possible emotional distress (or relief) associated with the death of a husband, widowed women in St. Eustatius also had to contend with the administrative duties that then fell upon them. At times, it was a burden that threatened to make them and their surviving relatives destitute.[5] Problems could include difficulty in getting the deceased husband’s relatives to pay support for minor children, difficulty acquiring funds from reluctant debtors, and simply the inability of a family to support itself when the main breadwinner was no longer around. Sometimes, when women advocated for themselves, their ability to receive assistance was proscribed by the authorities’ wish to preserve the whiteness of the free population. In Jamaica in 1797, for example, the Clergy Fund set up to support the widows and children of deceased Anglican clergymen restricted its assistance to those who behaved in a manner they considered proper, excluding those who had relationships with men of colour. Increasingly stringent eligibility requirements meant that many Jamaican widows and their families fell into poverty after the death of their husband or father.[6]

In other cases, widows could assert themselves in a way that might increase their wealth and social standing.[7] In eighteenth century Saint-Domingue, wealthy widows like Anne Rossignol and Marie Scipion (both free women of colour) could support themselves as housekeepers, retail and commercial actors, and real estate managers.[8] Even when they had no particular profession, women could exercise agency through socialising with their peers; corresponding with international contacts; managing finances, plantations, and households; arranging marriages for relatives; supervising enslaved people; and caring for children.[9] In Martinique, Manon Dessalles supervised sugar and coffee plantations between 1808, when her husband died, and 1814, when her son took over the estates. Even then, Manon still gave advice on how she thought the properties should be managed.[10] The high mortality rates made it necessary for women to have inheritance rights; the proper retention of family profits often relied upon them.[11] As Christina Walker suggests, we should therefore offer an “ambivalent account of the gendered dimensions of power” in a Caribbean context, an account that incorporates both the ability of free women to contribute to the status quo, and their attempts to subvert it.[12] In the following cases, I will show how four Statian widows (Elizabeth Pantophlet, Mary Simmons, Catharina Woods, and Sarah Jeems) dealt with interisland inheritances between St. Eustatius and St. Barths.

Figure 1: Woman and child in mourning dress (Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, 1809, Philadelphia Museum of Art, https://archive.org/details/repositoryofarts21809acke/page/n237/mode/2up).

Figure 1: Woman and child in mourning dress (Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, 1809, Philadelphia Museum of Art, https://archive.org/details/repositoryofarts21809acke/page/n237/mode/2up).

Complex Interisland Families: Elizabeth Pantophlet

Sometimes, interisland estates and complicated family structures could make circumstances particularly difficult for widowed women. In August 1796, Laurence Haddocks died intestate in St. Barths, leaving his wife, Elizabeth Pantophlet, behind him in St. Eustatius with their two children.[13] The absence of a will would entail a delay in Elizabeth receiving an inheritance from his interisland estate. The following year, one of his several children from his previous marriage, named James, died in St. Eustatius and left half his estate to Elizabeth and her children, and half to his brother John William and his children.[14] By 1800, neither of these estates had yet been settled and Elizabeth took matters into her own hands. She would use her existing contacts in and knowledge of St. Barths to try and settle the estates.

The Haddocks family had been in the Caribbean since the seventeenth century, present for example in Barbados in 1699,[15] while later becoming important in the Virgin Islands and Antigua,[16] and in Trinidad.[17] At the time of Laurence’s death, there were Haddocks family members in both St. Eustatius and St. Barths.[18] Meanwhile, the Pantophlet family first came to the Caribbean in 1741, as part of a drive to encourage white settlers in Jamaica.[19] This family could also be found on both St. Eustatius and St. Barths.[20] In March 1800, Elizabeth made the journey from St. Eustatius to St. Barths, where she was perhaps housed and assisted by her family members. There, she petitioned the local court, writing “your Petitioner having been a Widow for upwards of three years past […] with two Children to Support and Maintain, and not having it in her power to do so, without the assistance of her proportion of the property belonging to her late Husband”.[21] She wanted permission to appoint a representative in St. Barths, who could oversee the inventory, sale, and closure of the estate there. Despite her efforts, Elizabeth went away from St. Barths empty-handed.

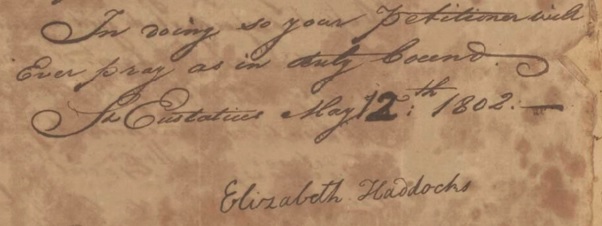

Figure 2: Elizabeth Haddocks signs her letter to the St. Eustatius island council concerning the settlements of her husband’s and stepson’s estates (NA 1.05.13.01 Inventaris van de archieven van St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba, 1709-1828 (1869), 22 1802 januari - 1802 september, page 36).

Figure 2: Elizabeth Haddocks signs her letter to the St. Eustatius island council concerning the settlements of her husband’s and stepson’s estates (NA 1.05.13.01 Inventaris van de archieven van St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba, 1709-1828 (1869), 22 1802 januari - 1802 september, page 36).

Two years later, there was still no movement. On May 12, 1802, Elizabeth petitioned instead the court in St. Eustatius. She complained that “part of the Estate of her deceased Husband is in this Island, and some negro’s at St Bartholomew […] That she is till this moment entirely unacquainted with the Situation of the Said Estate, and notwithstanding repeated applications made by her to Mr. John Wm. Haddocks, in this Island, and to Mr. Abraham Haddocks, in the Island of St Bartholomew, under whom the negro’s are, she has not been able to get any Settlement […] which she is intitled to, for her and her two children’s maintenance”.[22] Concerned that she might not get a reasonable sum, she coldly pointed out that the enslaved people working in St. Barths were valuable, but that they “depreciate dayly besides the risk of death”.[23] She also complained that she had been able to get nothing from James’ estate either, urging that the matter be settled so that she might know “what she with her children might have to depend on, and as she is from time to time put off, and the matter Continually delayed, and not able herself to act”. Finally, and seemingly as a last resort, she requested that the court appoint someone to bring these two estates to a close, a man who might wield the power of the court over her inheritance.[24] Inheritance of enslaved people in particular was a recurring concern for widowed women in the Caribbean, since many of them relied on this exploitation to provide a living in the absence of male protectors.[25] From Elizabeth’s perspective, through denying her access to the enslaved people in St. Barths, the male relatives of her late husband and stepson obstructed, for six years, her attempts to acquire proceeds that were vital for sustaining her family.

A week later, however, John William told the court a different story. He said that his “intention has never been to frustrate any of the Heirs of their right and as for being in possession of any property belonging to said Estate […] he is only in possession of two old and Infirm Negroes, whereas Mrs. Haddocks is in possession of the Greatest property, being a Dwelling and Out Houses with Seven or Eight Negroes belonging to said Estate”.[26] He also pointed out that it was impossible to settle James’ estate while his father’s was still unsettled. The difference in perspective between Elizabeth on the one hand, and John William and Abraham on the other, was structured by their differing circumstances and resources. Both these men were probably carpenters by profession, occupying a middling position in society and with a source of independent income.[27] Elizabeth, meanwhile, had no profession – her household, including her two minor children, had to be supported through the inheritance.

Although the fact that James named Elizabeth as one of his heirs suggests that there was a good relationship between them, her relationships with the brothers Abraham and John William was clearly strained, if not prior to the death of her husband, then certainly after it. It was easy for John William to evade responsibility for six years, all the while profiting from the labour of the people his father had enslaved, and then pretend to the court that he had done no such thing. It was also perhaps convenient to claim that the enslaved people in St. Barths were elderly and infirm, since the interisland nature of the inheritance meant that there was no easy way for the court to confirm this. In the end, the court appointed two men to take care of the estates – and we hear no more from Elizabeth.

Guardianship: Mary Simmons

Sometimes widows had more influence over the affairs of their deceased husband. For example, after the death of John Simmons, his wife Mary inherited his administrative duties. John had been named guardian of his relative’s minor children, Mary and Helin, and the elder Mary took over the responsibility for seeing that they were properly cared for. On February 3, 1802, she wrote to the St. Eustatius council that “Mr. Jn. Wm. Haddocks,[28] hath been appointed by the Honble. Court of this Island, as joint Guardian, with my decd. Husband Jn. R. Simmons, over the Minor Children, of Thoms. Simmons decd. / by name Mary & Helin, and as Mr. Jn. Wm. Haddocks, wishing to decline longer acting as Guardian your petitioner prays this Honble. Court, that two sufficient Guardians be appointed in their sted”.[29] Although the petition is from Mary, she signed it together with John William, who wanted to give up being a guardian. It seems that Mary had unofficially taken over her husband’s role as guardian since his death, and it is the occasion of the resignation of the other guardian that precipitates this appeal.

Just over two weeks later, Mary wrote again to the island council, this time together with the newly appointed guardians, William Mitchell and Nath Mussenden. Although Mary was no longer representing her deceased husband, she was still involved in the welfare of the two girls. Together with William and Nath, she requested “permission to dispose of by public sale, the negroes & furniture of Mrs. Helena Simmons decd. As they conceive it to be to the benefit of the Minors”. [30] In response, the court named William and Nath as executors of Helena’s estate, thereby giving permission for the sale, but excluding Mary from official responsibility.[31] One month later, Mary again petitioned the court, asking them to confirm a relevant sale that she had already made. She wrote, “your petitioner not knowing the requisite forms to be observed, had sold (on the 12 March 1799 at the Island of St Bartholomews) to Mr. Isaac […] Davids a certain Negro Woman named Nancy, the property of the Estate of Mrs. Helena Simmons, for the sum of Thirty Joes by private contract, as said Moneys wher for the purpose of defraying the funeral charges of said Mrs. Helena Simmons”.[32] This time, her name stands alone on the document. As in the case of Elizabeth and Laurence Haddocks, there were Simmons family members present in St. Barths as well as in St. Eustatius.[33] Mary may have used this network to help facilitate the sale of the enslaved woman Nancy. Here, we see Mary taking charge for the benefit of her husband’s wards. It may not have been the case that she was ignorant of the rules for selling enslaved people on other islands – instead, she may have reasoned that it was better to ask forgiveness than permission. Her decision might have helped avoid the kind of delay experienced by Elizabeth Haddocks.

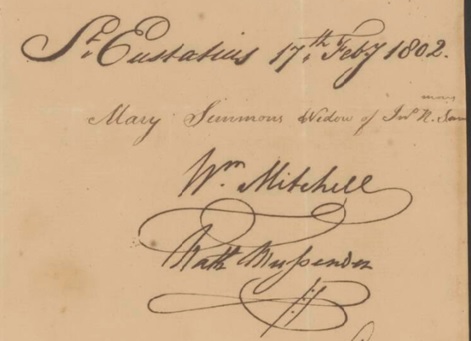

On each of these documents, when Mary’s name is accompanied by those of the other guardians, hers appears first (see Figure 3). This may indicate that she was the person taking the initiative in caring for these children. Widowed women often had to advocate for others around them, and could use the courts and appeal to local and foreign governments in order to do this.[34] Metropolitan stereotypes of creole women as litigious, unladylike, and jealous, may partially reflect the actions that Caribbean widows had to take after the death of their husbands.[35]

Figure 3: Mary Simmons’ name listed above those of the court-appointed guardians, William Mitchell and Nath Mussenden (Nationaal Archief 1.05.13.01 Inventaris van de archieven van St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba, 1709-1828 (1869). Inventarisnummer 208 1819 mei - 1822 augustus, page 15).

Figure 3: Mary Simmons’ name listed above those of the court-appointed guardians, William Mitchell and Nath Mussenden (Nationaal Archief 1.05.13.01 Inventaris van de archieven van St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba, 1709-1828 (1869). Inventarisnummer 208 1819 mei - 1822 augustus, page 15).

Death of a Widow: Catharina Woods and Sarah Jeems

Indeed, as we have already seen, widows in St. Eustatius were often in need of the court’s assistance to resolve inheritances where male parties were unwilling to help. On April 28, 1802, Catharine Woods (or Catharina Wood), widow of George Thomas Jeems, wrote to the court concerning debts from her late husband’s estate.[36] She had tried to settle this debt “in an amicable manner but to no effect” with a Mr. Jennings, and now asked the court “to appoint such persons on both sides, for the final close of said accts.”[37] It seems that requesting men appointed by the court to advocate on their behalf was a common strategy for widows in St. Eustatius, and usually it was a request that the court immediately granted. However, in Catharina’s case they directed her “to put a Copy of her Petition in the Hands of Mr. R. D. Jennings to Reply thereon by Wednesday next”.[38] The court therefore seems to have placed more trust in Mr. Jennings than Catharina did.

Catharina lived a further seventeen years as a widow and died intestate on May 18, 1819, her estate now presided over by her relative John Woods.[39] Her husband’s estate was still not settled, and its administration required interisland interventions. For example, in December 1819, John Woods had to arrange for the sale of an enslaved boy named James, in order to settle the Jeems’ debts to his own father, Richard Woods, in St. Barths.[40] Because both the Jeems family and the Woods family were present in St. Eustatius and in St. Barths, Catharina’s and George Thomas’ estates could therefore be managed by both families.[41]

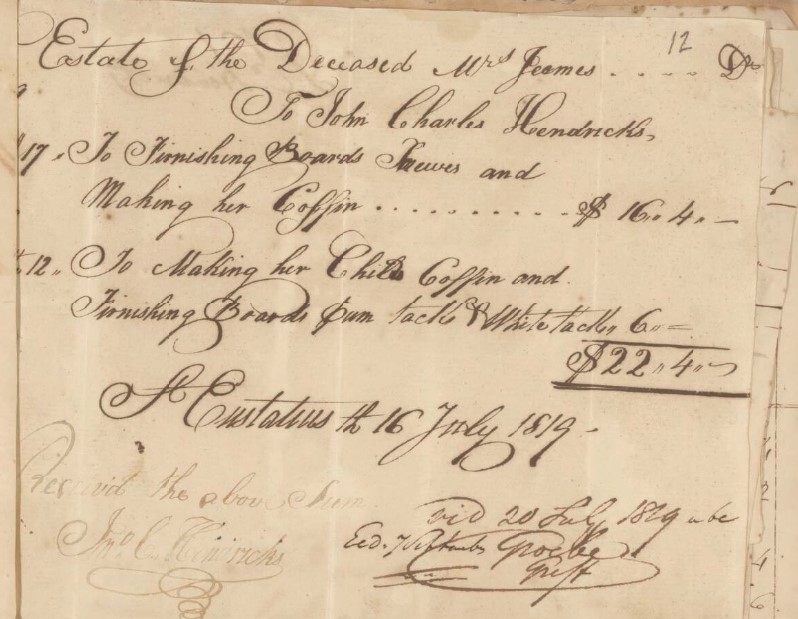

Unfortunately, Catharina was not alone in her death. The accounts of her estate include a bill for her coffin, but also a coffin for one of her children (see Figure 4).[42] The following bill reads “To Caroline Dewindt – To attendance in the Small Pox [and] To making her shroud”.[43] It is likely that Catharina died of smallpox along with her young child – despite the fact that a vaccine for smallpox was already available in the Dutch Caribbean.[44] That Catharina had small children at the time of her death implies that she had entered into another relationship after George Thomas’ death, although she did not remarry. Widows were attractive brides because they were likely to bring with them at least part of the fortune of their previous husband.[45] However, marrying might also mean losing control over one’s estate. Catharina may have wanted to protect her property by remaining legally single.

Figure 4: Bill for the construction of two coffins, one for Catharina Jeems and one for her child (NA 1.05.13.01 Inventaris van de archieven van St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba, 1709-1828 (1869). Inventarisnummer 208 1819 mei - 1822 augustus, page 17).

Figure 4: Bill for the construction of two coffins, one for Catharina Jeems and one for her child (NA 1.05.13.01 Inventaris van de archieven van St. Eustatius, St. Maarten en Saba, 1709-1828 (1869). Inventarisnummer 208 1819 mei - 1822 augustus, page 17).

It is conceivable that, at her death, Catharina was probably one of the more economically privileged women in St. Eustatius. The inventory of her estate includes furniture made of mahogany and cedar, four American chairs, and two tables.[46] She enslaved a man named William and two boys named Abraham and Louis in St. Eustatius; and a boy named James and three women named Charlotte, Betsy, and Sincerity in St. Barths.[47] Sincerity was freed on Catharina’s death, according to the terms of her mother’s will.[48] In June, Abraham, William, and Louise were sold along with the furniture.[49] In July, Charlotte was sold too, having been brought to St. Eustatius for the settlement of the estate.[50] By September, a list of outgoings could be compiled for costs relating to Catharina’s funeral and to the care of her surviving minor children. This latter was a task taken on not by court-appointed male guardians, but by Catharina’s widowed mother-in-law, Sarah Jeems, who would care for them until they were able to fend for themselves.[51] She did this despite the fact that they were not her own grandchildren.

The funeral preparations were elaborate, including decorations of black cambric and white ribbon,[52] and a shroud made by Caroline, who had cared for Catharina during “her last illness”.[53] The grave was dug at night, perhaps to shield her onetime benefactor John William Cross (or more likely someone he enslaved) from the heat, but perhaps also for discretion.[54] This was not the only assistance that John William offered the family after Catharina’s death. Each December between 1821 and 1826, he assisted Sarah in managing the children’s finances.[55] Perhaps John William was their anonymous father.

Sarah was also assisted in her role as guardian by the Orphan Vacant Estate Chamber. In St. Barths in May 1821, the enslaved woman Betsy was sold to pay for “the Clothing and maintenance” of Catharine Jeems, one of Catharina’s children. The sale was organised by the Chamber, which then forwarded Sarah the money.[56] In this case, financial and caring responsibilities passed from a widow of one generation to a widow of another. During her lifetime, Catharina may have played the system in order to ensure an inheritance for the next generation, while Sarah was consistent in acquiring support from the government, as well as from John William. We see the widows of St. Eustatius navigating a complex interisland inheritance, on behalf of the next generation.

Conclusions

For women widowed in St. Eustatius in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as Cecily Jones has noted for Barbados in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, their new status presented opportunities as well as challenges.[57] Kit Candlin has suggested several themes for the lives of women arriving in Trinidad between 1790 and 1820: independence, transnational mobility, wealth, and how race affected each of these.[58] Similar themes could also be applied to these widows from St. Eustatius, and they prompt us to ask further questions of the data. What did it mean for heirs when inheritances happened across islands? What were the similarities and differences in impacts for male and female widows, or for widows from different strata of society? Did foreign nationality influence the outcome of an inheritance? Were there more negative outcomes when husbands died without a will? These questions remain to be answered. However, here Elizabeth, Mary, Catharina, and Sarah’s experiences have shown not only the restrictions on widowed women in St. Eustatius, but also the ways in which they advocated for themselves and their dependents, using the colonial system to their own advantage. This often came at a cost to the people they enslaved. Additionally, the experiences of these four Statian widows underline the complex family connections between St. Eustatius and St. Barths at a time when one island was suffering economic decline while the other profited. Statian widows could proactively use these interisland family and inheritance relationships to support themselves and their dependents. It seems that interisland inheritances between these islands was common - both were places of belonging where citizens exercised ownership over people and property.

[1] Aaron Graham, 2021, ‘Gender, Family, Race, and the Colonial State in Early Nineteenth-Century Jamaica’, New West Indian Guide 95(3/4): 199-222.

[2] Han Jordaan and Victor Wilson, 2014, ‘The Eighteenth-Century Danish, Dutch and Swedish Free Ports in the Northeastern Caribbean’, in Gert Oostindie and Jessica Roitman, eds, Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680-1800; Linking Empires, Bridging Borders, Leiden: Brill, 273-308; Victor Wilson, 2019, ‘Contraband Trade under Swedish Colours: St Barthélemy’s Moment in the Sun, 1793-1815’, Itinerario 43(2): 327-347.

[3] Kit Candlin, 2010, ‘The Empire of Women: Transient Entrepreneurs in the Southern Caribbean, 1790-1820’, Journal of Imperial & Commonwealth History 38(3): 351-372.

[4] Johannes Hartog, 1984, ‘Life on St. Eustatius in 1790-1794, as Portrayed by Rediscovered Local Newspapers’, Gazette: International Journal of the Science of the Press 34(2): 137.

[5] Cecily Jones, 2014, Engendering Whiteness: White Women and Colonialism in Barbados and North Carolina, 1627-1865, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 92-101.

[6] Aaron Graham, 2021, ‘Gender, Family, Race, and the Colonial State in Early Nineteenth-Century Jamaica’, New West Indian Guide 95(3/4): 199-222.

[7] Jones, Engendering Whiteness, 92-101.

[8] Dominique Rogers and Stewart King, 2012, ‘Housekeepers, Merchants, Rentières: Free Women of Color in the Port Cities of Colonial Saint-Domingue, 1750-1790’, in Douglas Catterall and Jodi Campbell, eds, Women in Port: Gendering Communities, Economies, and Social Networks in Atlantic Port Cities, 1500-1800, Leiden: Brill, 357-397.

[9] Rebecca Hartkopf Schloss, 2022, ‘Furthering Their Family Interests: Women, French Colonial Households, and Mobility in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic’, Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 20(1): 113-151.

[10] Hartkopf Schloss, ‘Furthering Their Family Interests’.

[11] Christine Walker,2020, Jamaica Ladies: Female Slaveholders and the Creation of Britain’s Atlantic Empire, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 17-18, 170.

[12] Walker, Jamaica Ladies, 80-115; Trevor Burnard and Deirdre Coleman, 2022, ‘The savage slave mistress: punishing women in the British Caribbean, 1750-1834’, Atlantic Studies 19(1): 34-59; Patricia Mohammed, 1994, ‘Nuancing the feminist discourse in the Caribbean’, Social and Economic Studies 43(3): 135-167; Cecily Jones, 2003, ‘Contesting the boundaries of gender, race, and sexuality in Barbadian plantation society’, Women’s History Review 12(2): 195-232.

[13] Nationaal Archief Den Haag (NA) 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 35-38.

[14] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 35-36.

[15] Elizabeth Haddocks (The National Archives at Kew (TNA) CO 28/5, p. 380).

[16] Antigua, 1824 (TNA CO 7/10 p. 254).

[17] In the 1820s (TNA CO 318/76 p. 358).

[18] NA 1.05.13.01 p. 35.

[19] TNA CO 137/28, p. 233.

[20] Fonds suédois de Saint-Barthélemy (FSB) Vol. 146, image 33, accessible at www.swecarcol.ub.uu.se

[21] FSB Vol. 144, image 480.

[22] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 35-36.

[23] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 36.

[24] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 35-38. A copy of Elizabeth’s 1802 petition to the St. Eustatius court is also to be found in the St. Barths archives (FSB Vol. 147, images 581-583).

[25] Walker, Jamaica Ladies, 23.

[26] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 37.

[27] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 626; FSB Vol. 11, image 456.

[28] This is the same John William Haddocks who put off Elizabeth Pantophlet in the matter of her husband’s and stepson’s estates.

[29] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 13.

[30] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 15.

[31] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 16.

[32] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 17.

[33] Naturalisation of Abraham Simmons, December 15, 1812 (FSB Vol. 277, image 379); see also for example FSB Vol. 140, images 100-101; FSB Vol. 250, images 299-300.

[34] Aaron Graham, ‘Gender, Family, Race, and the Colonial State in Early Nineteenth-Century Jamaica’.

[35] Kathleen Wilson, 2002, The Island Race: Englishness, Empire and Gender in the Eighteenth Century, London: Taylor and Francis, 145; Burnard and Coleman, ‘The savage slave mistress’; Mohammed, ‘Nuancing the feminist discourse in the Caribbean’.

[36] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 23-24; NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 6.

[37] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 23-24.

[38] NA 1.05.13.01, 22, p. 24.

[39] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 6.

[40] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 28.

[41] On December 16, 1789, eleven Jeems family members were listed as heads of households in St. Eustatius, showing that the family had a significant presence on the island (NA 1.05.01.02, 1196, p. 410). There were also eight heads of household with the surname Wood in St. Eustatius in the same year (NA 1.05.01.02, 1196, p. 427). Jeems family members in St. Barths included Rebecca, who in 1810 got into a dispute about someone else’s pig eating her vegetables (FSB Vol. 161, images 443-444).

[42] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 17.

[43] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 18, 21.

[44] De Curaçaosche Courant, 1818-12-19 (Delpher).

[45] Wilson, The Island Race, 155; Walker, Jamaica Ladies, 178.

[46] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 6-7. Richard had resided in St. Barths since at least 1815, when he is mentioned in a fiscal’s report as the enslaver of a boy, named Boy (FSB Vol. 177, images 227-228). An Edward Woods is accused of adultery with married woman Susanna Basden in St. Barths in 1796 (FSB Vol. 141, image 84).

[47] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 6-7, 28.

[48] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 6-7.

[49] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 9.

[50] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 10.

[51] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 14-15.

[52] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 20.

[53] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 18, 21.

[54] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 21.

[55] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 31, 33, 35, 37, 39, 41.

[56] NA 1.05.13.01, 208, p. 30.

[57] Jones, ‘Contesting the boundaries of gender, race and sexuality in Barbadian plantation society’; Jones, Engendering Whiteness, 92-101.

[58] Candlin, ‘The Empire of Women’.