WORKING PAPER 2: Escaping and Maintaining Slavery in a World of Maritime Marronage

By Marie Keulen, 20 December 2021

In this working paper, Marie Keulen examines the attempts of enslaved men and women to escape slavery by crossing the Caribbean Sea from the Dutch island of St. Eustatius to foreign shores. While enslaved people made collective plans to run away, slave owners and colonial authorities continuously struggled to prevent this. Keulen explores this dynamic in the context of the early-to-mid nineteenth century, a period when the inter-island extradition of runaways was restricted due to abolitionist developments in the British Empire.

On an early Monday morning, in April 1833, two enslaved women, both named Mary, were waiting together with nine other enslaved people for a boat to pick them up from one of the outer bays of St. Eustatius. The day before, the women had agreed with a young sailor named William Burroughs to meet at the eastern point of the island, from where the sailor would bring Mary and Mary to the nearby British island St. Christopher, where they hoped to gain their freedom. When Burroughs and his two companions arrived at the agreed location, nine other enslaved people seem to have seized this opportunity for maritime escape and joined the two women. Perhaps the group of people who had gathered on the eastern shore were relatives, fleeing together with their loved ones; perhaps they were from the same owner, working on the same estate and escaping the same oppressive regime of slavery. However, the severe weather conditions of that day prevented the planned maritime escape from succeeding. Before the group of runaways could board Burroughs’ boat, it capsized in the pounding sea.[i]

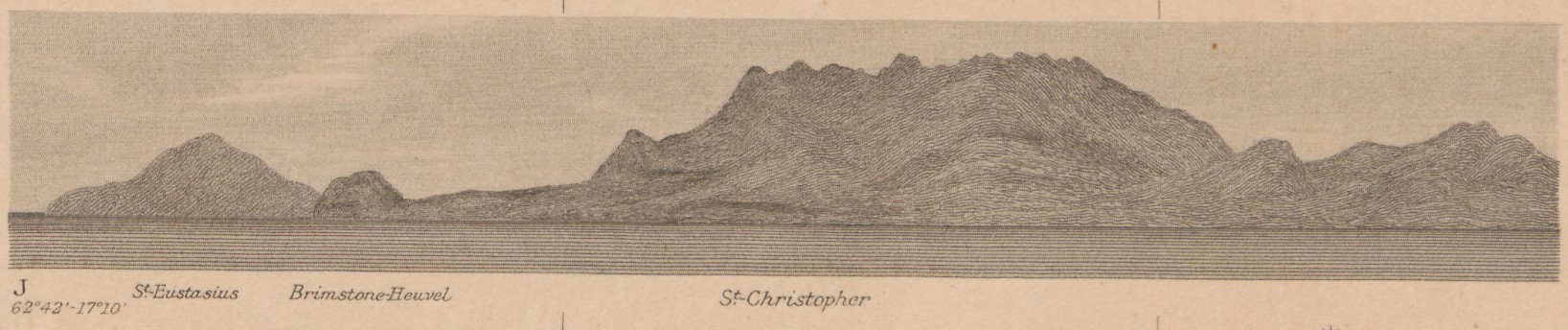

These eleven runaways were by no means the only enslaved people aiming to cross the waters that divided and connected the various islands of the Lesser Antilles. Many enslaved people attempted to run away from the islands they inhabited by facing the dangers of the sea and boarding a vessel, boat, or canoe. Some succeeded in these acts of maritime marronage and others did not – with the latter leaving more and better preserved archival traces in the journals, reports, and minutes of local colonial administrators. The Commander of St. Eustatius, the highest local colonial administrator on the Dutch island, regularly wrote about enslaved people who have attempted or succeeded to escape from the island. By far most of these maritime runaways fled to the closest neighbouring island, St. Christopher, which could be reached by travelling less than fifteen kilometres over the Caribbean Sea. The Dutch and British islands were so near that they were within clear sight of each other. On a bright day, it was even possible to see several other surrounding islands.[ii] This proximity – and visual presence – of other islands is a fundamental characteristic of the Lesser Antilles and was an important impetus for maritime marronage. The clear outlines of a foreign land on the other side of the sea, outlines of hills, coasts, and houses, must have encouraged hopes of freedom.

View of St. Christopher showing the outlines of the western part of the island from a sea-point perspective. The outlines of St. Eustatius, slightly more vague but still clearly visible, can be seen in the left background of the image. These coastal views, which show the contours of an island from the perspective of a ship approaching the island, were often included in nautical charts. Cutout from: J.G. den Engelse Wiemans, West-Indië St. Martijn, Saba, St.-Eustatius en omliggende eilanden, ’s-Gravenhage, Ministerie van Marine, Afdeeling Hydrographie, 1903, Leiden University Sepcial Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:53052.

Part of a map of the Dutch Leeward islands showing (from left to right) Saba, St. Eustatius, St. Christopher, and Nevis. At the top are two sea-perspective outlines of St. Eustatius and St. Christopher, one of which is shown above in more detail. To the left at the bottom, there is a small inset map of Oranjebaai, the main bay of St. Eustatius. Cutout from: J.G. den Engelse Wiemans, West-Indië St. Martijn, Saba, St.-Eustatius en omliggende eilanden, ’s-Gravenhage, Ministerie van Marine, Afdeeling Hydrographie, 1903, Leiden University Sepcial Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:53052.

Although it is impossible to know exactly how many enslaved people ran away from St. Eustatius to St. Christopher or other islands – a point stressed by Jessica Roitman – things can be said about the significance of maritime marronage on this small island. Approaching this question from the perspective of frequency and the threat of depopulation, Roitman concludes that for the Dutch Leeward islands, “it is very doubtful that these escapes ever comprised any significant percentage of the total enslaved population.”[iii] Maritime runaways were a constant but small group, “never higher than a few per cent yearly.”[iv] On a local level, this small but continuous stable flow of runaways was of great significance – for the enslaved people who succeeded or failed in reaching foreign shores, for the slave owners who lost their property and consequently (part of) their source of income, and for the enslaved people who were not directly involved but for whom the successful acts of escape could give hope. Both the successful and unsuccessful attempts of escape created friction in the system of slavery and slave labour that planters, owners, and authorities tried to maintain by all means.

On St. Eustatius, the local authorities were involved in a continuous struggle to prevent enslaved people from fleeing the island, to discourage free people to help them do so, to punish those who were involved in one of these acts, and to get the inhabitants’ “fugitive property” back in case their slaves did, in the end, succeed to escape. This included the promulgation of various ordinances, during both the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, regulating the use and safeguarding of small boats and canoes to prevent these small crafts from falling into the hands of slaves aiming for an escape.[v] An explicit regulation on maritime marronage only appeared in 1834, when the concerns of the then-Commander Van Raders about the many runaways to St. Christopher came to a head and coalesced into two related ordinances: one prohibiting the transportation of slaves to foreign colonies, and any kind of complicity, the other rewarding those who inform the government of any runaway conspiracies. In explaining the need for these regulations, Van Raders explicitly complained about “the constant attempts of the slaves to escape in groups with canoes or other craft to the neighbouring British Islands, in which they are sometimes supported and aided by free people from this island as well as from St. Kitts”.[vi]

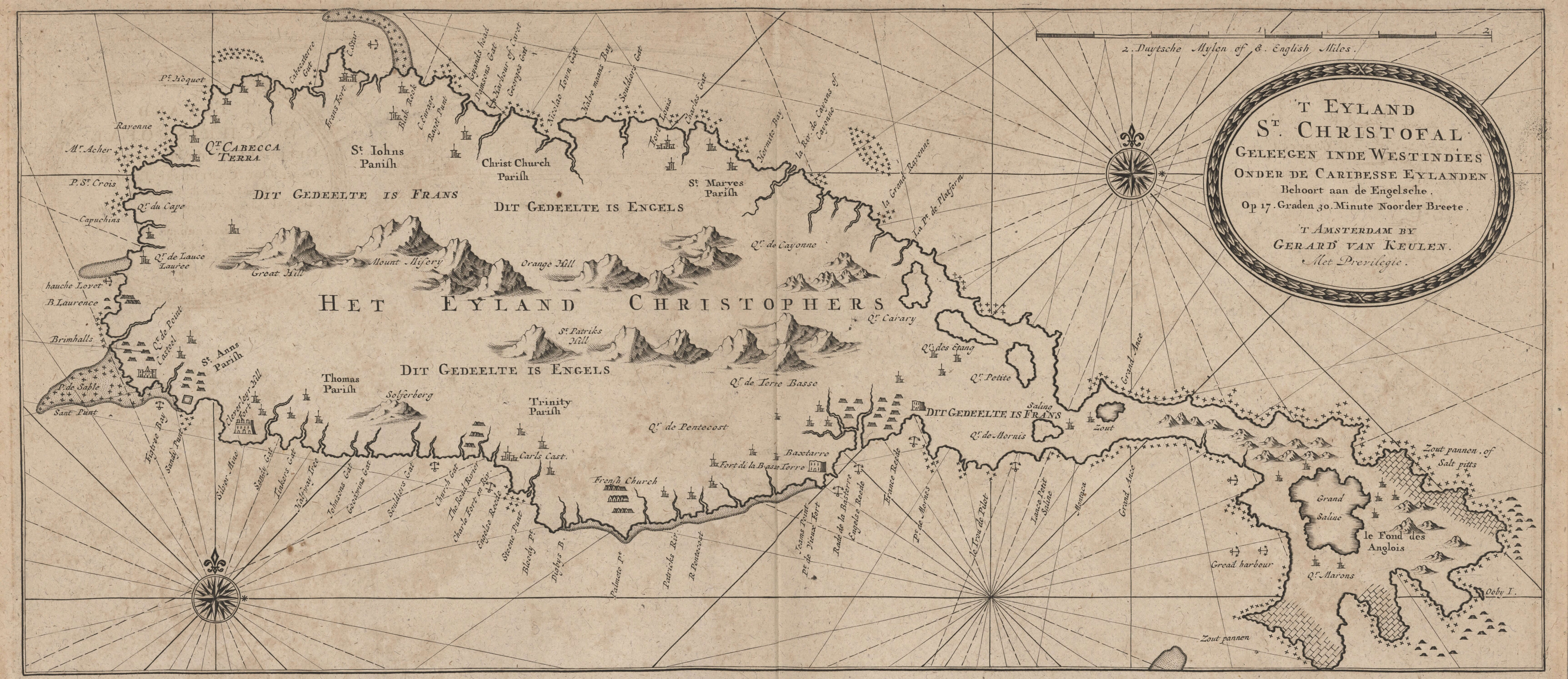

Map of St. Christopher. Gerard van Keulen, 'T Eyland St. Christofal Geleegen inde Westindies Onder de Caribesse Eylanden, ca. 1719, Danish National Library, KBK 2-867, pl. 14.

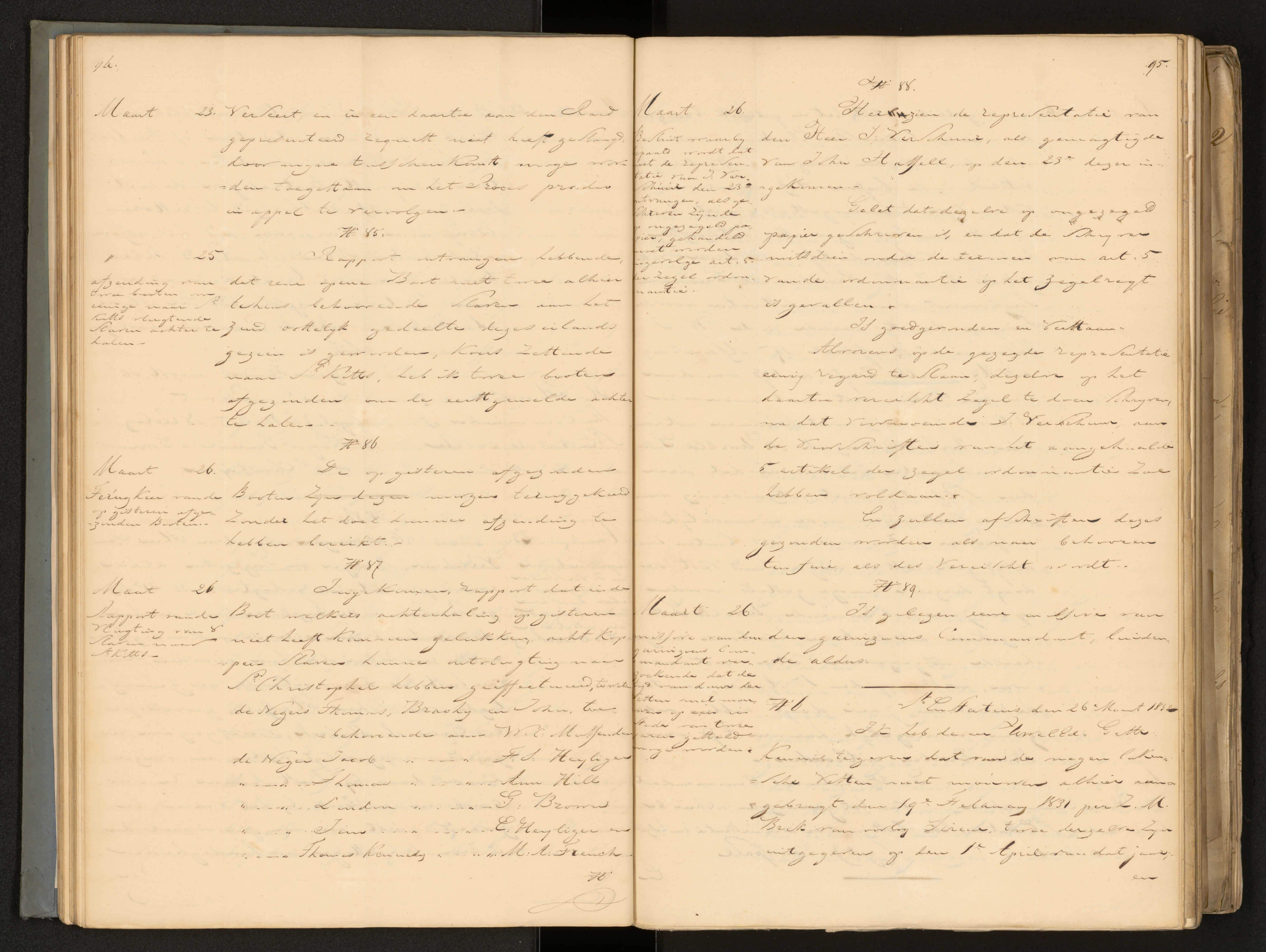

In the years leading up to these ordinances, various runaway cases are reported by the Commander of St. Eustatius. In 1832 and 1833, four distinct groups of enslaved people successfully ran away to St. Christopher, involving a total of 24 people.[vii] However, the fact that these enslaved people had succeeded in reaching the British shores did not stop the Dutch colonial authorities from trying to reclaim and recapture them. Incited by the planters and owners whose enslaved labour force ran away, Commander Van Raders wrote several letters to the Governor of St. Christopher seeking to mobilize his assistance in the extradition of the escaped slaves from St. Eustatius. Although inter-imperial cooperation in the extradition of runaway slaves was not uncommon in the Lesser Antilles, in the early-to-mid nineteenth century, this practice came under pressure due to abolitionist developments in the British Empire. In 1825, the “Act to amend and consolidate the Laws relating to the Abolition of the Slave Trade” went into effect, which prohibited the extradition of escaped slaves who arrived in British territory.[viii] Returning enslaved people to their owners in foreign territories was viewed as tantamount to the illegal importation or exportation of slaves. As a consequence, maintaining slavery became more challenging for non-British slave owners in the Lesser Antilles.[ix]

Aware of the possible difficulties of cooperation, Van Raders backed up his request of extradition to the Governor of St. Christopher by proposing an agreement of mutual exchange of runaways. Not only did enslaved people run away from St. Eustatius to St. Christopher, but there were also numerous examples of enslaved men and women trying to escape slavery by taking the reverse route. Thus, when at the beginning of 1832, the authorities of both islands were looking at each other for their escaped slaves, Van Raders used this opportunity to propose, “in the principle of reciprocity,” the mutual extradition of Dutch slaves who had fled to St. Christopher and British slaves who had fled to St. Eustatius.[x] Despite his multiple letters, however, the Commander of St. Eustatius could not persuade his British counterpart to agree to such cooperation and none of the enslaved men and women were handed over to the owners they escaped from.[xi] This outcome left the slave owners, planters, and administration of St. Eustatius with a feeling of disappointment, impotence, and frustration. Whenever enslaved men and women succeeded in reaching British islands, they would have no power to reclaim and recapture their property. The Commander of the Dutch island was well aware that within this context maintaining slavery had become more challenging: enslaved people would continue to seek their freedom in the lands so close and visible from their homes, and it was “impossible to completely prevent their escape.”[xii]

Page from the journal of the Commander of St. Eustatius Van Raders in which he writes about the escape of eight slaves to St. Christopher. NLHaNA, 2.10.01, inv. no. 3862, Gouvernements Journaal, image 49.

There were also unsuccessful plans of maritime marronage, cases in which the colonial authorities did succeed in preventing enslaved men and women from escaping the island. It is these cases – of which better records are preserved – that can tell us more about how acts of maritime marronage came into being and about the people involved. Although the existence of maritime marronage in the Lesser Antilles, and the Caribbean in general, is widely known among historians, there is still little known about what happened before and after the actual attempts of escape.[xiii] How did people plan their escape? What were the logistics involved in the collective efforts of planning to run away from an island by crossing the sea? And what happened to the people who did, in the end, succeed in reaching foreign shores governed by British authorities who would not return them to the owners they fled? By looking at the colonial records of cases in which authorities succeeded in capturing, prosecuting, and punishing enslaved people who had attempted to run away we could begin to answer the question of what happened before enslaved people boarded a boat to cross the sea that lay ahead of them.

An example is the unfortunate attempt of the two enslaved women named Mary and the group of people joining them. The case led to extensive legal proceedings against the three free sailors Burroughs, Hyndmans, and Brown for their planned role in facilitating a slave escape. The fact that enslaved people could plan their escape by having contact with and making agreements with free sailors was an alarming and frightening observation for slave owners and local authorities. They hoped to set an example by sentencing these three men to severe corporal punishment. Reading the accusations and verdicts of these sailors, one is left wondering about their motivations. Although their behaviour is seen as alarming, the Court of Civil and Criminal Justice does not seem interested in the question of why they helped a group of enslaved people escape the island – only the fact that they did it. Burroughs, who agreed to smuggle two enslaved people from St. Eustatius to St. Christopher, did not seem to have personal connections to any of the people involved. Perhaps the agreement between the enslaved women and Burroughs was some sort of business agreement, with the latter obtaining a financial gain.

Mary and Mary, who are pointed out as “the heads of the conspiracy of escape,” and the nine enslaved people joining them, were not prosecuted by the Court of Civil and Criminal Justice and nothing is mentioned about the consequences of their failed escape for their lives or the punishments they had to endure. It seems likely that this was left to their owners. If the Court of St. Eustatius was involved in their punishment, it did not leave the same extensive archival traces. The fact that the two people involved in planning the escape, by making contact with sailors and by making an agreement with them, were two women is remarkable. Within the historiography, women are not often described as the main figures involved in planning maritime marronage. From the sources that have been preserved about this case, it is not clear how Mary and Mary were able to make the agreement they did. Coming from St. Christopher, Burroughs arrived on a Saturday at St. Eustatius, where he came to conduct trade. It is on this day or the next that Mary and Mary must have noticed his presence in the harbour of the island, Orange bay. On Sunday evening, when the sun had already set and they were less vulnerable to watching eyes, they approached Burroughs and made their deal. If the agreement did indeed involve money, then the two enslaved women must have been in a position to either earn money of their own or steal it. Although the agreement with the sailors was made in the evening just before their escape, the active planning of both Marys had probably started much earlier than that.[xiv]

Coloured lithograph of the port of Willemstad on the Dutch Antillean island Curaçao showing the many different kinds and sizes of vessels in a nineteenth-century Lesser Antillean harbour. Besides the portrayed ship entering Willemstad, the infrastructure of the harbour consisted of many small boats. Cutout from: Jacob Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, colored lithograph from Gezigten uit Neerland's West-Indien, naar de natuur geteekend, en beschrevendoor G.W.C. Voorduin, [1860-1862], John Carter Brown Library.

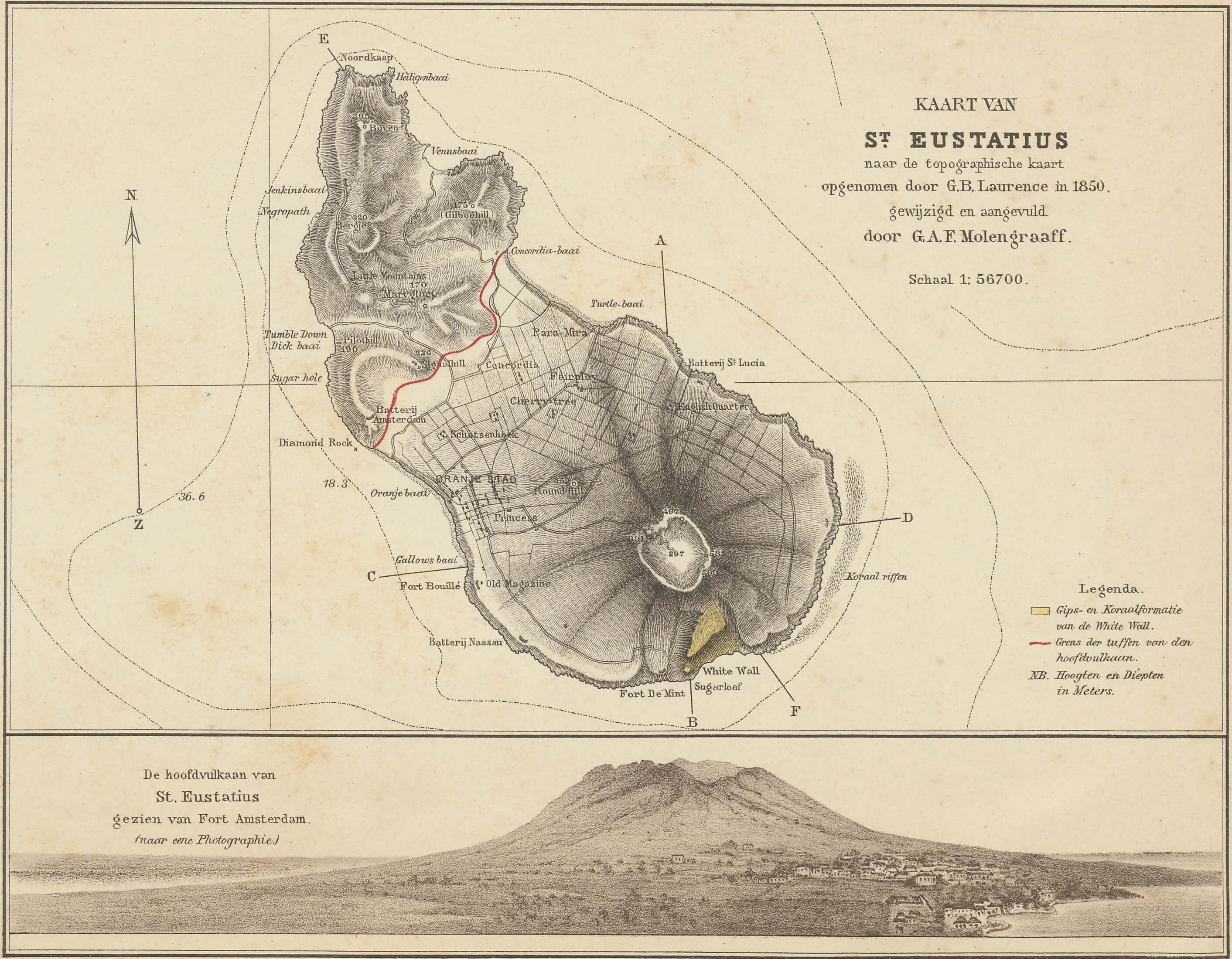

In the years before and after this case, the local authorities were confronted with two other runaway attempts, or “conspiracies”. In these cases, enslaved people did not try to use an existing boat for their flight, by either stealing it or by making a similar agreement to the one Mary and Mary had made, but they had instead planned to flee the island with a self-made canoe, manufactured from tree stumps. More than twenty enslaved people were involved in the plans of escaping St. Eustatius with these canoes. The canoes, about five and three and a half meters long, were made and hidden in the “burnt down” volcano on the southeast of the island, “a mere shell [where there] are growing large trees and bushes”.[xv] It was only by mere coincidence, writes Commander Van Raders, that the canoes and the runaway attempts were discovered. Maybe the increased surveillance of small craft, induced by the ordinances regulating their use, made it more difficult for enslaved people to steal the boats and canoes so widely used on the island. As this case shows, even without access to the omnipresent boats used for fishing and transportation on and around the island, enslaved people sought ways to reach foreign shores.

Late eighteenth-century engraving of St. Eustatius portrays the harbour, Orange Bay, and the inactive volcano on the southeast of the island. The volcano is also called The Quill, which comes from the Dutch word ‘kuil’, meaning 'pit' or 'hole'. Gezigt van het Eyland St. Eustatius, [approximately 1780], etching/copper engraving, 26 x 41,5 cm, Leiden University Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:53042.

The more than twenty people involved in the making and hiding of the two canoes were from different slave owners and estates. Only scattered fragments of the written traces that were produced by the colonial clerks have been preserved.[xvi] These documents tell us that the key planner of the second escape attempt with a self-made canoe was Benjamin Burnham, who had run away from St. Christopher to St. Eustatius two years earlier, and who was now trying to go back with a group of other enslaved people. Whereas at the time of his first maritime escape, the Governor of St. Christopher had identified him as a free person of colour, the authorities in St. Eustatius had always regarded and treated him as an enslaved person.[xvii] Burnham was interrogated in the investigation of the canoe case, as well as four other enslaved people: Thom Phips, Henry, Peryanna, and Lidy. Only the interrogation of Phips can now be found in the Dutch National Archives.[xviii] Seeking refuge in the volcano after running away from his owner Charles Mussenden, Phips describes running into Burnham, who was working there on his canoe which “was nearby finished”. Phips, who was from St. Christopher and who, perhaps, had waited for an opportunity like this, joined Burnham’s plan and assisted him in finishing the boat.

Burnham must have planned his attempted escape to St. Christopher a long time before meeting Phips in the volcano. Making a dugout canoe is very laborious and would have taken hundreds of hours of work.[xix] Burnham and the people involved in his plan would have needed tools and knowledge to turn a tree stump into a boat with which they could cross the fifteen kilometres of sea separating St. Eustatius from St. Christopher. Once finished, they would also need to carry their canoe from the volcano where they were making the canoe to the coast from where they could depart without being noticed by the authorities. The volcano was a good place to hide both yourself and a boat but it was also a place that was not very easy to get to. This would have made it difficult to move easily and quickly between a hideout place in the volcano and an estate. Yet staying at the volcano was also challenging as it was a difficult place to provide yourself with food and water. These circumstances point out that the two runaway attempts with self-made canoes were long-planned escapes, in which we know more than twenty enslaved people were involved. Together they cooperated and carefully planned their escape, just as Mary and Mary had done. Although the number of people who made a similar choice, planning to leave behind their homes and communities, was relatively small, they tell an important story of slavery and freedom in the Lesser Antilles. In a region where small islands of different imperial authorities – British, French, Dutch, Spanish, Danish, and Swedish – were so close that they were in each other’s field of vision, maritime marronage was literally and metaphorically on the horizon. Within this context, slave owners and colonial authorities struggled to maintain, recapture, and reclaim the enslaved people who looked across the sea for their freedom.

Late nineteenth-century map and an aerial view of St. Eustatius. It portrays the volcano on the southeast part of the island as a prominent presence in the landscape. Gustav Adolf Frederik Molengraaff, Kaart van St. Eustatius, 1886, Leiden University Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:876330.

[i] National Archives, The Hague (NLHaNA), 1.05.08.01, Inventaris van het archief van de Gouverneur-Generaal der Nederlandse West-Indische Bezittingen, inv. no. 490, Kopie-notulen van de Raad van Civiele en Criminele Justitie van St. Eustatius, 9 April 1833 (images 57-60), 11 April 1833 (images 60-70), 18 April 1833 (images 71-73), 22 April 1833 (images 73-77), 25 April 1833 (images 77-96); NLHaNA, 1.05.13.02, Inventaris van de archieven van St. Eustatius en Saba, inv. no. 30A, Civiele en crimineele processtukken, William Burroughs 18 April 1833 (images 1-6).

[ii] George Coggeshall, Thirty-Six Voyages to Various Parts of the World, Made Between the Years 1799 and 1841, Selected from His MS. Journal of Eighty Voyages (New York: Putnam, 1858), p. 252.

[iii] Jessica Roitman, ‘Land of Hope and Dreams: Slavery and Abolition in the Dutch Leeward Islands, 1825–1865’, Slavery & Abolition, 37.1 (2016), 375–98 (p. 384) <https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2016.1140457>.

[iv] Roitman, ‘Land of Hope and Dreams’, p. 383.

[v] For the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries see: Jacob Adriaan Schiltkamp and Jacobus Thomas de Smidt eds., West Indisch Plakaatboek. Publikaties en andere wetten betrekking hebbende op St. Maarten, St. Eustatius, Saba. 1648/1681-1816 (Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1979). For the early-to-mid nineteenth century see: NLHaNA, 2.10.01, Inventaris van het archief van het Ministerie van Koloniën, inv. no. 3843, Reglementen, publicaties, tarieven, ordonnanties en andere verordeningen, uitgevaardigd voor St. Eustatius en Saba.

[vi] NLHaNA, 1.05.08.01, inv. no. 730, Stukken door de gezaghebber van St. Eustatius en Saba, en de procureur-generaal van Suriname aan de gouverneur-generaal gezonden betreffende publicaties over weggelopen slaven: “de geduurig gemaakt wordende pogingen van slaven om in partijen met kanoos of andere vervoertuigen naar de naburige Engelsche Eilanden te vlugten waarin zij soms ondersteund en geholpen worden door vrijlieden zoo hier als te St. Kitts s’huis behoorende”.

[vii] NLHaNA, 2.10.01, inv. no. 3862, Gouvernements Journaal, no. 87 (image 49), no. 155 (image 80), no. 164 (image 83); NLHaNA, 1.05.13.02, inv. no. 3, Journalen van de commandeur, no. 102 (image 36).

[viii] Acts of the British Parliament, Slave Trade Act 1824, 1824 Chapter 113, 24

June 1824.

[ix] Jessica Roitman writes about the implications of the 1825 act and the British abolition of slavery in 1834 for the Dutch Leeward islands in the following articles: Roitman, ‘Land of Hope and Dreams’; Jessica Roitman, ‘The Price You Pay: Choosing Family, Friends, and Familiarity over Freedom in the Leeward Islands’, Journal of Global Slavery, 1.2–3 (2016), 196–223 <https://doi.org/10.1163/2405836X-00102003>.

[x] NLHaNA, 2.10.01, inv. no. 3862, no. 75 (images 43-45).

[xi] NLHaNA, 2.10.01, inv. no. 3862, no. 80 (images 46-47); no. 83 (images 47-48), no. 92 (images 52-53), no. 94 (images 56-57).

[xii] NLHaNA, 2.10.01, inv. no. 3862, no. 176 (images 91-92): “zal het onmogelijk blijven hunnen ontvlugting geheel tegen te gaan”.

[xiii] See for example the work of Julius S. Scott, who convincingly shows that maritime marronage was an integral part of the Caribbean region: Julius S. Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution. (Brookly: Verso, 2018) 59-68.

[xiv] For the archival documents of this case see NLHaNA, 1.05.08.01, inv. no. 490, 9 April 1833 (images 57-60), 11 April 1833 (images 60-70), 18 April 1833 (images 71-73), 22 April 1833 (images 73-77), 25 April 1833 (images 77-96).

[xv] NLHaNA, 1.05.08.01, inv. no. 730 (images 4 and 41). For the description of the volcano see Coggeshall, p. 251.

[xvi] For the preserved minutes of the Court of Civil and Criminal Justice mentioning one of the canoe cases see: NLHaNA, 1.05.08.01, inv. no. 490, 12 June 1834 (images 409-416).

[xvii] For the documents about Benjamin Birmham’s escape from St. Christopher to St. Eustatius see: NLHaNA, 2.10.01, inv. no. 3862, no. 62 (image 38), no. 75 (images 43-45), no. 94 (images 56-57).

[xviii] NLHaNA, 1.05.13.02, inv. no. 30A, Civiele en crimineele processtukken, Thom Phips 5 June 1834 (images 11-16).

[xix] This is shown by archaeological experiments reconstructing dugout canoes with prehistorical and historical tools. See for example Havley Messer and Krissy Hogeweg, ‘Eto Perro Experimental Dugout Canoe Project’ (Florida State University Libraries, Undergraduate Research Symposium, 2015); Andrea Johnson, Douglas McLearen, James Herbstritt, and Kurt Carr, ‘The Pennsylvania Dugout Canoe Project’, Pennsylvania Heritage, Fall, 2006.