WORKING PAPER 4: Prospect or Necessity: Migration Among Free People of Color in St. Thomas, 1803

By Hannah Hjorth, 12 July 2022.

In this working paper, Hannah Hjorth uses the 1803 registration of free people of colour residing in Charlotte Amalie (St. Thomas) 1803 to examine popular migration routes and potential motivations for mobility in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

In the early morning of February 8, 1803, Anna Margret and her 18-year-old daughter, Maria Penonna, walked from their home in Kings Quarter to the seat of the island commander in the town of Charlotte Amalie on the Danish island of St. Thomas. They were on their way to be registered as free people of colour residing on the island. The previous day, public spaces in Charlotte Amalie had resounded with the beating of drums, as the official document announcing the registration was read aloud. The two women might have heard the drums on their way home from work, or they might have been notified by a neighbour later the same evening. Either way, they were able to put other chores aside that day, and at nine o’clock they were standing in front of the registration counter ready to answer questions about their occupation, place of birth, and legal status.

Figure 1: There are no illustrations left of the buildings housing St. Thomas’ highest official, the Commander, which Anna Margret and Maria Penonna visited in February 1803. The drawing above is a sketch of the new building constructed in 1816. Courtesy of the Danish National Archives: The West Indian Local Archives, Koloniernes Centralbestyrelse, Vestindisk Kontor. 337 33. Kort og tegninger, 337 124 Udkast til ny bolig for kommandanten på St. Thomas, sydfacade og profil af grunden 1816, tegnet af Christian Daniel Gottlob Brücker 3

Anna Margret and Maria Penonna were both born on St. Thomas and had lived there all their lives. They would not have failed to notice that the last five years had brought significant changes to the demographics of their town. From 1797 to 1803, the group of free people of colour had more than sextupled, from 239 individuals to around 1500 individuals.[i] That would have been a change felt by people like Anna Margret and Marie Penonna in their everyday life. Additionally, they might have felt that local authorities were fearful, keeping a watchful eye on these changes in town demographics and on free people of colour in general. Already in 1774, the Governor General of the Danish islands, Peter Clausen, had expressed concern about the growing population of free people of colour, noting that many were unable to prove their freedom. In legislation from the Danish West Indies in the late eighteenth century, this concern appears at regular intervals. Sometimes focusing on the lack of free letters, on enslaved people pretending to be free, or, with a more economical twist, on the presence of so-called “worthless strangers” (i.e., unyttige fremmede ).[ii]

The concern and fear exhibited on St. Thomas in 1803 were not unique in the late eighteenth-century Caribbean. The years 1776-1824 are known as the age of revolution, referring to the impact of three major events in this period; the American revolution, the French revolution, and the Haitian Revolution.[iii] Across the Caribbean, white people were living in societies where they were greatly outnumbered by enslaved Africans, and they depended on aid from far-away European imperial powers. On the French islands, news of the revolution in their home country might at first have filled colonists with hopes of improvements to their rights and autonomies. Such hopes, however, quickly turned to concerns about how ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity might influence both enslaved and free people of colour. Soon, the white colonists and colonial administrators shifted towards controlling mobility and news to prevent the revolutionary upheaval of the French islands from spreading to the rest of the Caribbean.[iv]

It is against this historical background that we can understand why the Danish West Indian Governor General Walterstorff found it necessary to order the registration of the free people of colour on St. Thomas, the only free port in the Danish colonies and a centre for trade and people from different parts of the Caribbean.[v] In February 1803, Walterstorff appointed a committee consisting of five prominent citizens from the island. They were to register all free people of colour in the town of Charlotte Amalie, noting how they would provide for themselves, how they could prove their freedom, and where they had resided since 1789.[vi] When the registration was complete four days later on February 12, they had registered no less than 1521 men, women, and children.

The registration was done to control free people of colour. It also, however, allows us to obtain a fine-grained picture of who they were. Indeed, looking closer at the registration shows a very diverse group. They came from all over the Lesser Antilles; some were young adults, and others were children; some travelled alone, others with family. In what follows, we will see that interisland mobility existed for both men and women, but also that mobility did not mean the same thing to everybody and that there were different push and pull factors shaping people’s choices as they moved around between islands or stayed in one place. Focusing on the two biggest migrant groups on St. Thomas, namely those from Curaçao and Martinique, and comparing these with the population born on St. Thomas, this paper shows how different these three groups were from one another.

A history of politics and revolution

Anna Margret and her daughter were born on St. Thomas and had resided there all their lives. While her daughter was born free, Anna Margret had been born into slavery. It was the former General Governor, Christian Lebrecht von Pröck, who had freed her when she was a child. Now a 40-year-old woman, Anna Margret supported herself by baking bread, and her daughter worked as a seamstress, a profession she shared with 352 other women of colour in the town (53%), making it by far the most common occupation for women on St. Thomas.

These two women might have been neighbours of Guilamma Jeuor Pierre, who also resided in the King's Quarter. Guilamma was a sailor, 21 years old and born in Puerto Rico, although he had spent the last 14 years in Port au Prince, before he came to Kings Quarter on St. Thomas in July 1802. Guilamma did not have a free letter. His only documentation was a passport from St.-Domingue, and in addition, he had the support of one Peter Savis, a citizen of St. Thomas, who vouched for him. Having resided in St.-Domingue during the revolution, and being young, mobile, mixed-race, and freeborn, he almost perfectly fits the description most often found in the literature on free people of colour in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Figure 2: Conversation with a Private Soldier of the Black Army on his Excursion in St. Domingo. Courtesy of John Carter Brown Library: J. Barlow, Marcus Rainsford, 1805, ink on paper - JCB Archive of Early American Images (lunaimaging.com)

The history of free people of colour is often told as a history of politics and revolution. Indeed, in historical works on the Caribbean in this period, one character stands out and is so well described that it is almost possible to visualize him stepping out of the pages. This character is a military man, a member of one of the militias consisting of free people of colour, and a physically and mentally agile person who stands upright in his uniform. He is concerned with politics, and he bends an ear when sailors from the neighbouring islands drop comments about a potential disturbance or revolt amongst enslaved or free populations.[vii] He might be a revolutionary, inspired by what he has heard about the events taking place in France in 1789. He has political visions, he attacks structures of oppression, and he writes to governors (sometimes even directly to European kings) to extend the freedoms and rights of free people of colour. He is focused on holding on to his status as a free citizen, which he has to lay claim to and negotiate daily.[viii]

The historiography of the Caribbean in the age of revolution describes how exceptional free individuals of colour took destiny into their own hands and challenged social orders. Sources such as legal records, letters between government officials, petitions, and interrogation records, are mobilized to tell the stories of people who stood out - both in a positive and a negative sense. Historian Jane G. Landers, for instance, uses such evidence to reconstruct the lives of men who personify the active participation of free people of colour in the political struggles of the period.[ix] Yet, while these types of sources may tell the story of remarkable women as well as remarkable men, they seldom allow us to get a sense of the history of the people who went from cradle to grave without ever being the subject of a governor’s letter.[x] This, however, is possible by looking into the data available in the 1803 registration and proceedings of free people of colour in St. Thomas. By studying the information provided there, it is possible to get a bit closer to people who for one reason or another stayed out of other official documents.

Geographical spread among free people of colour in Charlotte Amalie in 1803

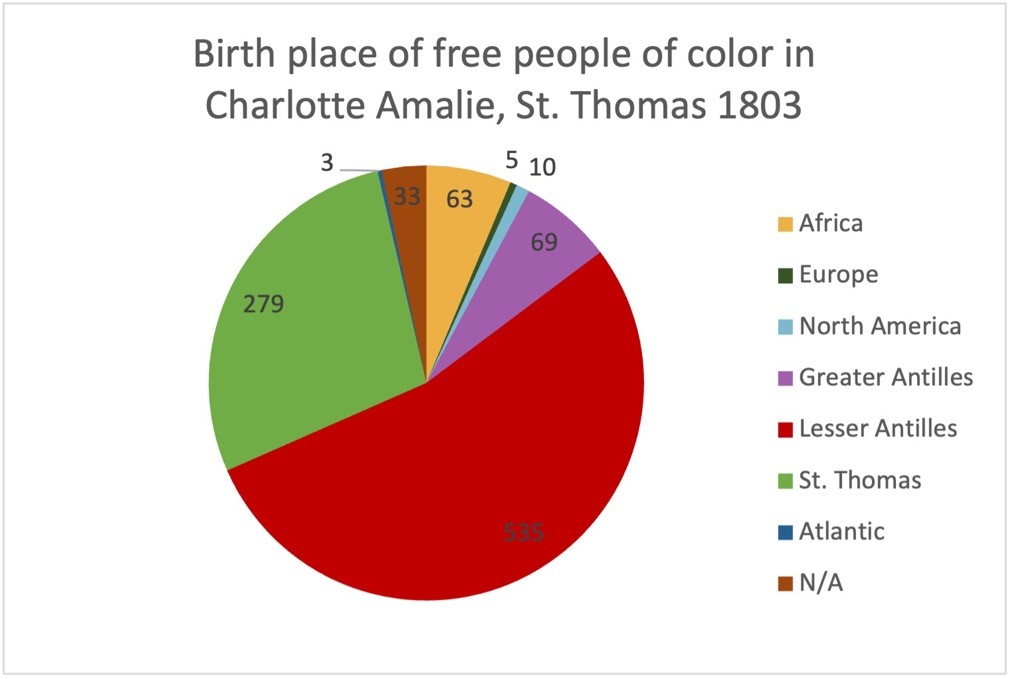

Figure 3: The birthplace of free people of colour, who resided in Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas, in 1803. Source: Digitalization of the translated data in Knight, & Prime, L. de T. (1999). St. Thomas 1803: crossroads of the Diaspora: the 1803 proceedings and register of the free coloured inhabitants in the town of Charlotte Amalie, on the island of St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies. Little Nordside Press. Digitalization by Hannah Katharina Hjorth for In The Same Sea 2022 [xi]

Free people of colour in Charlotte Amalie at the beginning of the nineteenth century were at the same time a geographically diverse and locally interconnected group. On the one hand, almost three-quarters of them can be characterized as immigrants (either forced or voluntary). This group of people includes those born in West Africa, Martinique, different places in North America, and even Johannes Moll, a man of African descent aged 83 and born on the Danish island of Ærø, who was brought to St. Thomas at the age of 10. On the other hand, three-quarters of this group were born within the Lesser Antilles, which points towards a high degree of interisland mobility for free people of colour in the region, significantly higher than the mobility which linked the region to Africa and the Greater Antilles.

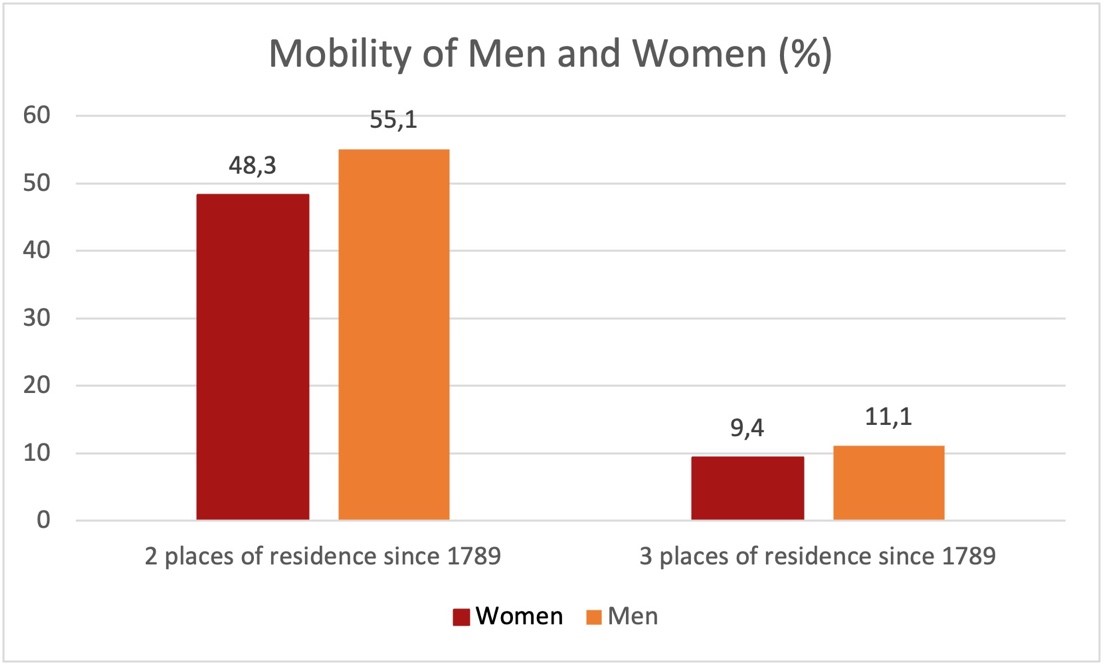

Besides the variety of birthplaces, the group was also characterized by quite a high level of mobility. 62% state that they have resided in at least one place other than St. Thomas since 1789 and around 10% even list three or more places in which they had resided during the 14 years between 1789 and 1803.[xii] As figure 2 shows, this mobility was not limited by sex. Only slightly more men than women moved around.

Figure 4: Free people of colour in Charlotte Amalie, who stated two or three places of residence since 1787, divided by sex. Stated in the percentage of the total amount of women/men. Source: Digitization of the 1803 registration, 2022

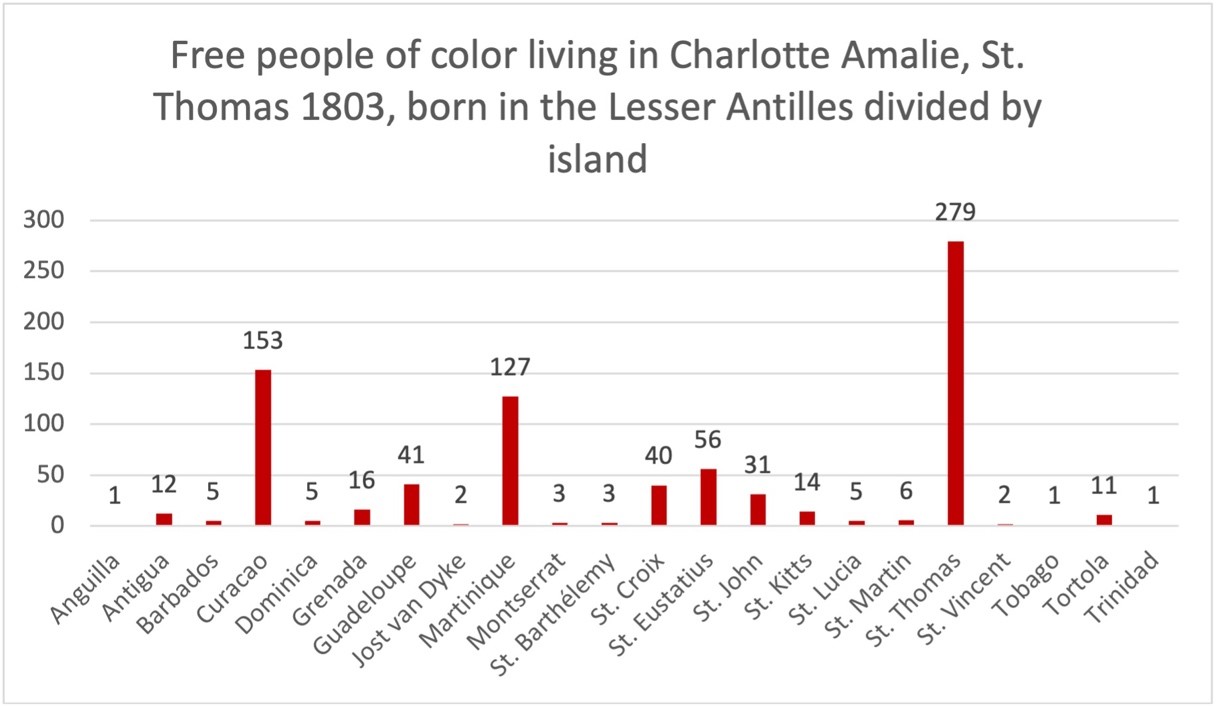

Zooming in on the 814 people born in the Lesser Antilles, three islands stand out – St. Thomas, Martinique, and Curaçao. Combined, these three birthplaces make up 56% of the free non-white population. Occupied by three different colonial powers, geographically as far from each other as you might come within the Lesser Antilles, and quite different in size, these three islands help show the diversity of the group of free people of colour who resided in Charlotte Amalie in 1803.

Figure 5: Free people of colour born in the Lesser Antilles, who was residing in Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas, in 1803. Divided by island. Source: Digitization of the 1803 registration, 2022

Families from Martinique and young women from Curaçao

The Bordois family also lived in King’s Quarter. The mother, Victoir Bordois, had been manumitted on Martinique in 1779 at the age of 18, and all her four children had been born free. The group of children counted two boys and two girls, the eldest being Louis Eli, aged 20. Victoir, Louis Eli, and Teus, a female relation residing with them, were the main providers in the family. Victoir and Teus produced and sold jam, while Louis Eli worked as a goldsmith and had taken his younger brother Sacat Simon, aged ten, as his apprentice. The two teenage sisters, Rosetta (who also had a child of her own) and Reus, both helped their mother with housework and jam-making. Although the family had resided in St. Thomas for the past eight years, Victoir was now planning to move her family somewhere else. When asked how she expected to provide for herself if she was allowed to stay, she told the registering officer that she only intended to stay for a short while and that she would be taking the younger children with her when she left.[xiii] We do not know exactly why Victoir and Teus were planning to leave St. Thomas with their family – or indeed if they did so. Perhaps they hoped to be able to return to Martinique; perhaps they were uniting with other family members on another island. What we do know is that Louis Eli did not wish to follow his family to another island. A young man, and a goldsmith by profession, he might have felt his prospects would be better if he stayed where he was.

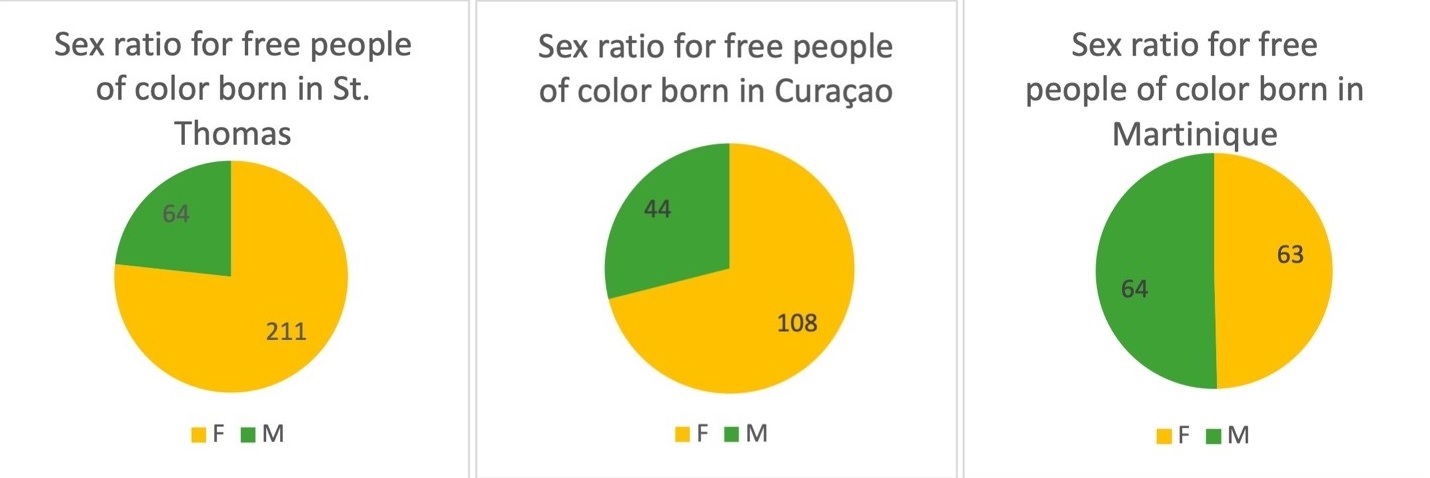

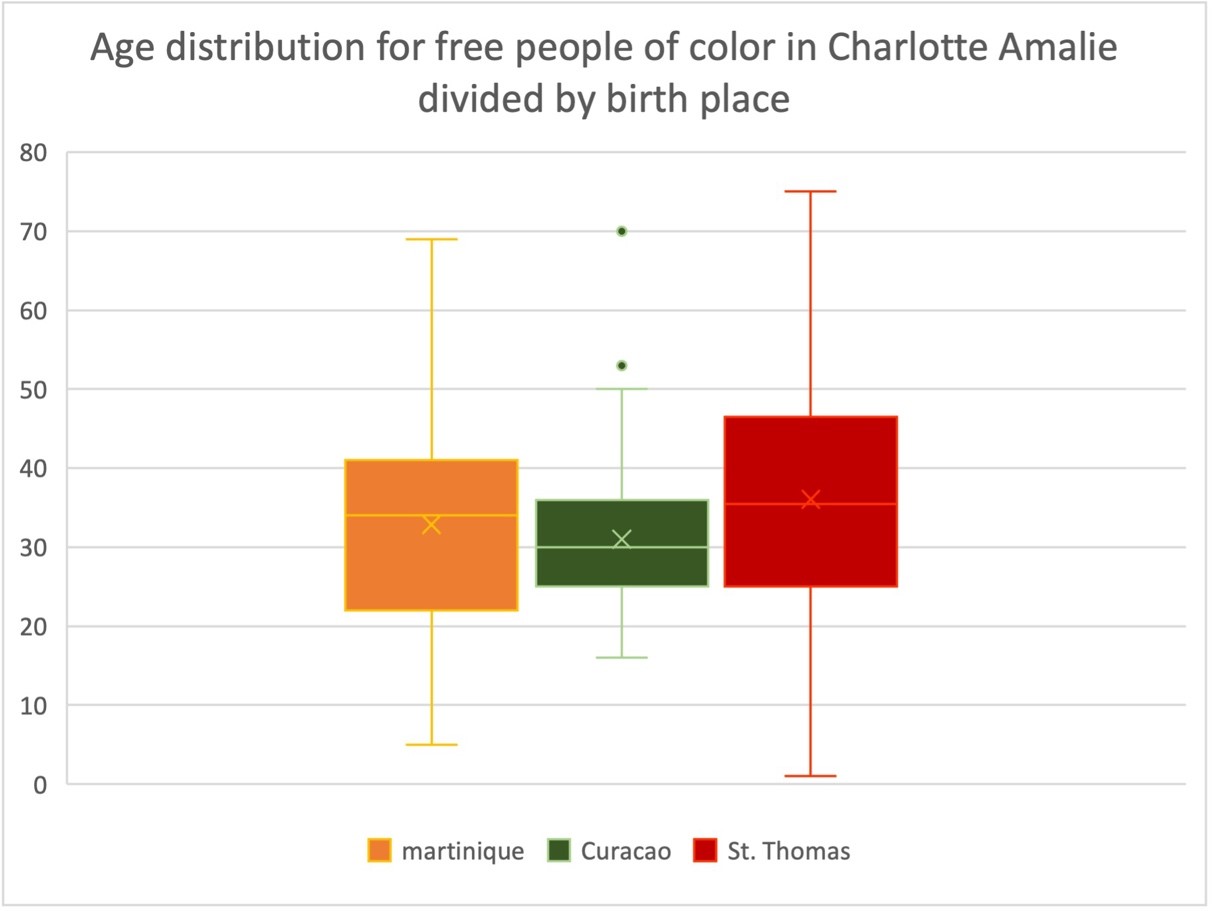

The Bordois family were not the only family from Martinique who had chosen to settle in Charlotte Amalie around the turn of the eighteenth century. A comparison between the sex ratio of the three different population groups under scrutiny shows that the group of Martinican immigrants differed from the two other groups by having an almost 50-50 sex ratio. This also differs from the overall group of free people of colour, where 67% were women and 33% were men.[xiv] Indeed, it appears that free people of colour from Martinique, who came to St. Thomas, were travelling as families whereas those from Curaçao travelled alone. The evidence makes it difficult to determine family ties, since individuals were registered as single persons, and not as members of households, as would otherwise be customary in census registrations at the time.[xv] But when combining data about the sex ratio and the age distributions, there are indications that the Bordois family might have been more rule than the exception for immigrants travelling from Martinique to St. Thomas. Figure 5 shows that whereas the Curaçaoan immigrants were quite homogenous in age (there are a mere 11 years between the 1st and 3rd quartiles), the Martinican group were more spread out. This either means that a lot of people from Martinique in different age groups decided to go to Charlotte Amalie independent of each other in this period, or – more probably - that many travelled as families. Either way, there are quite substantial demographic differences between the two groups. The reason for this might may pertain to the differences between Curaçao and Martinique in the late eighteenth century.

Figure 6a-c: Pie charts showing the sex ratio for free people of colour born in Curaçao, St. Thomas, and Martinique. Source: Digitization of the 1803 registration, 2022

Figure 7: Boxplot showing the age distribution for the migration groups from Martinique and Curaçao, compared with the group of free people of colour from St. Thomas in 1803. Source: Digitization of the 1803 registration, 2022.

Conditions for free people of colour in Curaçao and Martinique

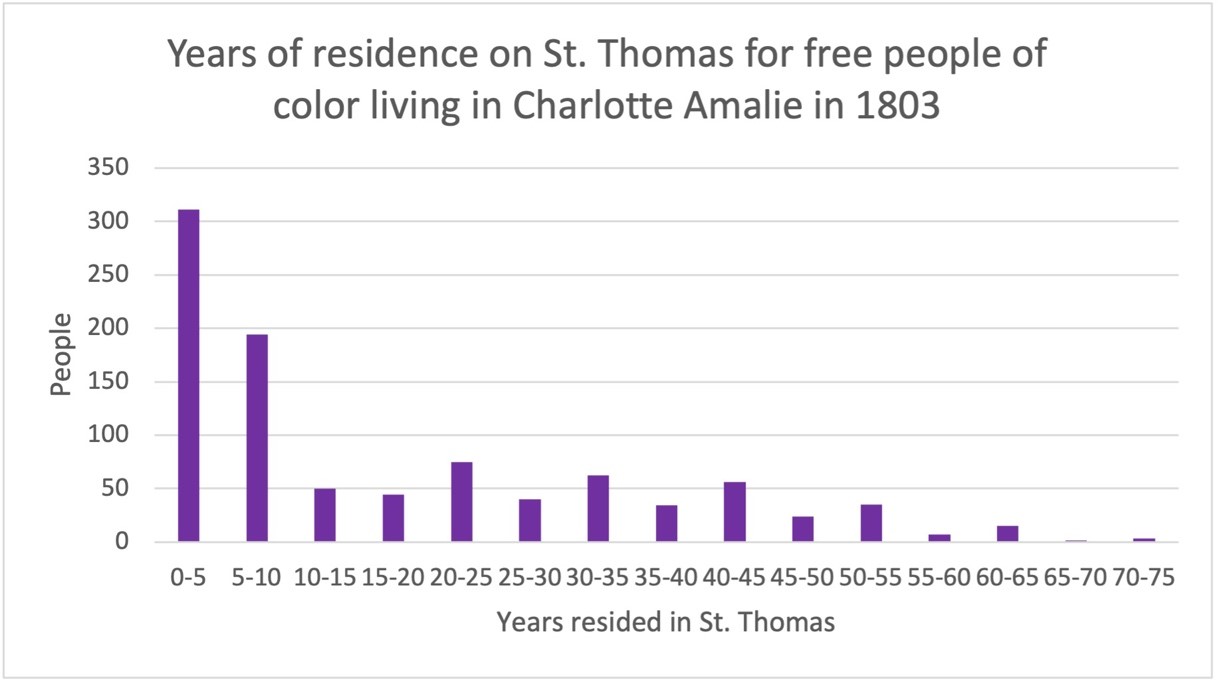

The majority of free people of colour had only resided in Charlotte Amalie for 10 years or less. This means that we might get a better idea of their motives for moving from one island to another by looking into the conditions on other islands during the age of revolution.

Figure 8: The number of years free people stated they had resided on St. Thomas in 1803. Source: Digitization of the 1803 registration, 2022

Like Charlotte Amalie, Willemstad (Curaçao) was a free port and a place for trade and maritime occupations. Most of the free non-white population on Curaçao lived in Willemstad and were occupied as carpenters, sailors, seamstresses, and traders.[xvi] This made them more mobile than free people of colour on plantation-based islands, and as the centre for regional trading shifted from Willemstad to St. Thomas, many free people of colour might have found it profitable to follow trading routes to a place that somewhat resembled their birth town.[xvii] The demographics of Willemstad among free people of colour also resembled those on St. Thomas, with higher manumission rates for women than men, making it likely that there would be a majority of women among the migrants.[xviii]

Figure 9: The harbour in Willemstad. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library: Cutout from Jacob Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, colored lithograph from Gezigten uit Neerland's West-Indien, naar de natuur geteekend, en beschrevendoor G.W.C. Voorduin, [1860-1862]

Free women of colour in both Willemstad and St. Thomas were engaged in market activities, which both provided them with a small income, and inserted them into networks with people from other places in the Americas.[xix] When the women from Curaçao came to St. Thomas, they eventually almost ousted local tradespersons by tapping into these networks, using their connections with Spanish traders in their favour, and causing great concern amongst commission members, who felt the need to specify this in their presentation of the registration results:

... but among these are a considerable number of women from Curaçao and other places, who are occupied as seamstresses, hucksters and forestallers, who by the knowledge of the Spanish language and their customs are the natives superior […] the commission finds this class of people very unwanted and harmful ... [xx]

The trade routes of the Lesser Antilles presumably influenced the migration routes. Not only were Willemstad and Charlotte Amalie similar to each other in terms of employment opportunities and free port status, but there was also a lot of traffic between the two islands.[xxi] With ships going back and forth on a more or less daily basis, the opportunities for planning travel to St. Thomas might have been better than for other destinations. And indeed, frequent trading also allowed migrants on St. Thomas to maintain ties with family and friends they had left behind in Curaçao.

Curaçaoan immigrants likely moved to St. Thomas seeking a more economically stable future. If the economic prospects for traders and sailors changed in Willemstad, it would make sense that especially the younger part of the population, who might not yet have had the advantages of strong professional networks, would go to Charlotte Amalie.

Figure 10: Soldiers standing in front of Fort Louis in 1796. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library: Cooper Willyams, print, hand-colouring, 1796, N. E. view of Fort Louis in the Island of Martinique.

In Martinique, on the other hand, the years between 1789 and 1803 were marked by political rather than economic turmoil. The British occupation of the island, which ran from 1794 to 1802, came with stricter control of free people of colour and put a stop to the different efforts to claim freedom and rights for enslaved and free people of colour.[xxii] Under British rule, free people of colour were facing a number of legal restrictions. Their inheritance rights were circumscribed, and they lost their right to citizenship, which they had enjoyed for a short period between 1792 and 1794.[xxiii] Liberties earned before January 27, 1793, were declared void, and planters were able to curtail freedom rights. The so-called Old Regime of pre-1789 was restored, meaning worsened conditions for both enslaved and free people of colour.[xxiv] Additionally, in the fall of 1794, a dispute between the attorney general and British General Grey about reopening the ports caused a food shortage and worsened living conditions in Martinique.[xxv]

Comparing mobility in Curaçao and Martinique can be understood by the conventional migratory concepts of push factors and pull factors. Free people of colour in Curaçao might have seen mobility as an opportunity to make a better life for themselves. Instead of staying behind on an island where prospects for employment in trade, skilled work, or shipping were declining, they might have been driven by a hope for a better future pulling them towards settling in Charlotte Amalie. On Martinique on the other hand, they were pushed off the island, rather than being pulled in hopes of improving their life situations. For free people of colour from Martinique, it was not a question of prospects as much as a question of securing their safety in society pushing them back into slavery. Yet, both groups were a far cry from the man of politics and struggle found in late eighteenth-century Caribbean historiography.

Members of the Borders family probably feared for their safety when they decided to move from Martinique to St. Thomas in 1795. As they felt freedom rights declining in a politically tense environment, they were looking for a safer place to stay, and like many other families from Martinique, they chose to travel to Charlotte Amalie. Their history also shows how strategies, circumstances, and prospects changed for individuals over time. Even though his mother, Teus, and his younger siblings were looking for other places to settle in 1803, Louis Eli found that forging or maintaining networks as a young skilled worker in Charlotte Amalie served him better than using his ability to move between islands within the Lesser Antilles.

The 1803 registration of free people of colour on St. Thomas challenges us to rethink our understanding of migrants in the Lesser Antilles. It was not only the male sailors, soldiers, and revolutionaries who used mobility, networks, and connections to move between islands. It was also the middle-aged tradeswoman, the young seamstress with a child on her arm, and even whole families who, either voluntarily or forced by external circumstances, were able to move between islands.

[i] The numbers for 1797 come from Hall (1992) p. 180 and are also used by Jeppe Mulich in In A Sea of Empires p. 118. They should be interpreted with some caution, since Hall is basing his numbers on somewhat scattered data, and he undercounts the population of free people of colour on St. Thomas in 1815 (Hall, 1980, p. 56).

[ii] VILA, General Guvernøres Arkiv, Plakatbog 1744-1791, fra 1783-1791, Schimmelmann, St. Croix, 1785-01-15

[iii] Higman, B. W. A Concise History of the Caribbean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 141.

[iv] ibid, p. 146

[v] Oostindie, Gert. “Dutch Atlantic Decline During ‘The Age of Revolutions.’” In Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680–1800, 29:309–335, 2014., p. 304

[vi] National Archives and Record Administration (NARA), record group 64, Essential Records Concerning Slavery and Emancipation, Censuses: St. Thomas Commission for the Registration of the Free Blacks: Proceedings and Register of Free Blacks, 1803.

[vii] See for instance Scott, Julius Sherrard, and Marcus Rediker. The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution. London; Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2018. Scott, 2018, p. 23 or Mulich, Jeppe. In a Sea of Empires: Networks and Crossings in the Revolutionary Caribbean, 2020., p. 68

[viii] Mulich, 2020, p. 120

[ix] See for instance Landers, 2010, p. 4,

[x] See for example Candlin, Kit & Pybus, Cassandra. (2014). Enterprising Women: Gender, Race, and Power in the Revolutionary Atlantic. University of Georgia Press.

[xi] The following graphs, charts and tables consist of the 997 people listed directly in the source and not the children listed beside their mother's names. Therefore you’ll see 997 used as the total number of people. source: Digitalization of the translated data in Knight, & Prime, L. de T. (1999). St. Thomas 1803: crossroads of the Diaspora: the 1803 proceedings and register of the free coloured inhabitants in the town of Charlotte Amalie, on the island of St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies. Little Nordside Press. Digitalization by Hannah Katharina Hjorth for In The Same Sea 2022.

[xii] Digitization of the 1803 registration, 2022

[xiii] NARA: Censuses: St. Thomas Commission for the Registration of the Free Blacks: Proceedings and Register of Free Blacks, 1803, p. 32.

[xiv] Digitization of the 1803 registration, 2022

[xv] NARA, St. Thomas Commission, 1803, p. 1.

[xvi] Jordaan, Han: Slavernij & Vrijheid op Curaçao, Zutphen: p/a Uitgeversmaatschappij Walburg Pers., 2013, p. 11

[xvii] Ibid, p. 216

[xviii] Jordaan, 2013, p. 286 and Hall, 1992, p. 150

[xix] Joordan, 2013, p. 81

[xx] NARA, St. Thomas Commission, 1803, 1803, p. 4 (my translation)

[xxi] Data from Fricke, Hansen, Hjorth & Simonsen: “Vessel Itineraries in De Curaçaosche Courant: A Quantitative Microhistory, 1816-1818 and 1825-1826” Blogpost from June 15, 2022: Vessel Itineraries in De Curaçaosche Courant: A Quantitative Microhistory, 1816-1818 and 1825-1826 – University of Copenhagen (ku.dk)

[xxii] David Geggus, "The Slaves and Free Coloreds of Martinique during the Age of the French and Haitian Revolutions: Three Moments of Resistance" in The Lesser Antilles in the Age of European Expansion eds. Robert L. Paquette and Stanley L. Engerman (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1996), p. 285

[xxiii] ibid, p. 293 and p. 289

[xxiv] Cormack, W. (2019). Patriots, Royalists, and Terrorists in the West Indies: The French Revolution in Martinique and Guadeloupe, 1789-1802. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. https://doi-org.ep.fjernadgang.kb.dk/10.3138/9781487519148, 232

[xxv] ibid, p. 235